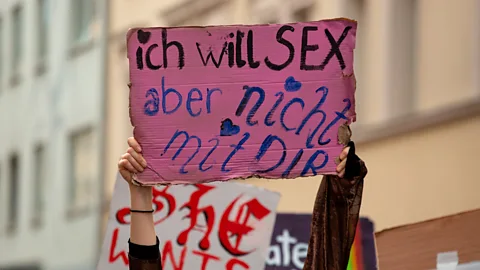

Why sexual assault survivors forget details

Getty

GettyAnd four other misconceptions about sexual violence.

Barely a week goes by now without another case of rape or historic sex abuse being splashed across the news and picked over by critics. Yet misunderstanding about the nature of sexual violence leads to distorted opinions, which can further enhance victims’ feelings of shame, guilt and self-blame. Common myths about rape and sexual assault also undermine jurors’ ability to objectively assess the facts when such cases come to court.

Here are five common myths and the facts behind them.

1. Most sexual assaults are committed by a stranger

The narrative of a woman being sexually assaulted while walking down a dark alleyway may still play out on many TV screens. But in the real world, rape and serious sexual assault is far more likely to occur in the home and at the hands of someone familiar. In England, Wales and Australia, around one in five women have experienced sexual violence at least once during their lifetime; the US’s national sexual violence survey similarly estimated that one in five women, along with one in 71 men, have been raped.

Getty

GettyBut in the UK, for example, a separate report found that the perpetrator was a stranger in only 10% of rape and serious sexual assaults, while in 56% of cases it was the victim’s partner, and for the remaining 33% it was a friend, acquaintance, or other family member.

2. A ‘real’ sexual assault survivor always reports immediately

According to UK Home Office data, 46% of recorded rapes were reported on the day they took place – while 14% of people took more than six months to report that they’d been assaulted. If the victim was a child, they were even more likely to delay coming forward: just 28% of those aged under 16 reported the offence on the day it happened, while a third waited for longer than six months.

That is just for assaults that ultimately are reported. Many others are not. In the US, for example, studies have estimated that two out of three sexual assaults never are reported.

Getty

GettyThere are many reasons why some people either delay reporting or never do, as testified to by the “#WhyIDidn’tReport” hashtag on Twitter. “A lot of people don’t report because they don’t want the perpetrator to go to prison: maybe they’re in love with them, or it’s a family member, or it’s a partner and are reliant on their income,” says Nicole Westmarland, director of Durham Centre for Research into Violence and Abuse in the UK. “Another common reason I hear from students is that they don’t want to ruin the rest of the person’s life.”

Even so, “there is no evidence that suggests the timing of when you report is linked to the genuineness of the report", she says.

3. If assaults were reported immediately, it would be relatively easy to investigate and press charges

It is true that survivors of rapes and sexual assaults who come forward quickly are more likely to undergo a forensic medical examination, which involves taking swabs and samples from the body to identify the source of any semen, saliva, or DNA. Examiners also document injuries such as cuts, grazes or bruising, which could support allegations of force.

But undergoing a physical examination doesn’t necessarily mean an offender will be caught and convicted, or even that the case will be investigated – as demonstrated by the hundreds of thousands of rape kits that sit untested in police departments and forensic storage facilities across the US. And physical evidence tends to be less helpful if the person you’re accusing is a partner or close acquaintance. “Most cases these days don’t come down to whether sexual intercourse happened – or forensic evidence of intercourse. They come down to whether that intercourse was consensual or not,” says Westmoreland.

According to UK Home Office data, 26% of rapes and serious sexual assaults reported on the same day resulted in someone being charged, dropping to 14% once a day or more has elapsed. Those who reported the offence on the day it took place also had significantly higher odds of seeing their case get to court – although it made less of a difference if the victim was under the age of 16. In the US, meanwhile, separate reports have found that only 18% of reported rapes lead to an arrest and 2% result in a conviction.

4. If you didn’t ‘really’ want it, you’d fight back

People vary in their response to rape and sexual assault. In her 2008 book, Serial Survivors, the University of Wellington criminologist Jan Jordan describes the very different techniques employed by 15 women who were sexually assaulted by the same man: some tried talking to him; others fought back; still others tried to mentally remove themselves from the situation – a process psychologists refer to as ‘dissociation’.

Another study, which examined 274 police reports from the US, found that only 22% of survivors resisted rape through fighting and screaming. The majority (56%) tried begging and pleading with their offender, while others reported feeling ‘frozen with fright’. Different scenarios were more or less effective in different circumstances. Women who fought back, for example, were more likely to avoid rape – but they also ran a higher risk of greater physical injury if a weapon was present. On the other hand, pleading, crying or reasoning with the perpetrator was associated with increased physical injury if the attack took place indoors and increased sexual abuse if environmental intervention (such as someone intruding) occurred.

Getty

GettyIt is also important to recognise that people can’t necessarily control their responses in such situations. Some enter a state of involuntary physical paralysis known as ‘tonic inhibition’ when confronted with an extreme threat. A Swedish study of 298 women who visited an emergency rape clinic within a month of having been sexually assaulted found that 70% reported significant tonic immobility and 48% reported extreme tonic immobility during the assault – and that those who experienced it were also more likely to develop post-traumatic stress disorder and severe depression in the coming months.

5. Traumatic experiences scramble your memories: maybe you’ve misremembered what happened

Many people who have been raped or sexually assaulted often claim to have vivid memories of certain images, sounds and smells associated with the attack – even if happened decades earlier. Yet when asked to recall exactly what time of day it was, or who and what was where at any given time – the kinds of details police and prosecutors often focus on to establish the facts of a crime – they may struggle or contradict themselves, undermining their testimony.

“There is this tragic discrepancy between what is expected within the criminal justice system and the nature of trauma memories and how people are likely to be reporting them,” says Amy Hardy, a clinical psychologist at Kings College London.

This is because memories of traumatic events are laid down differently to everyday memories. Usually we encode what we see, hear, smell, taste and physically sense, as well as how that all slots together and what it means to us – and together, those different types of information together enable us to recall events as a coherent story. But during traumatic events our bodies are flooded with stress hormones. These encourage the brain to focus on the here and now, at the expense of the bigger picture.

Getty

GettyThis makes sense from an evolutionary perspective. “When we are under threat, it is much better that we focus on what we are experiencing, which triggers us into fight, flight or freeze-type responses, than to focus on the bigger meaning and making sense of it,” says Hardy. “We also know that if people dissociate during trauma – where the cognitive part of the brain shuts down and they go a bit spacey or numb – it exaggerates this fragmentation process, so their memories have an even more here-and-now-type quality.”

Hardy has examined the impact of these memory processes on survivors’ experience of reporting sexual assault to the police. She found that those who reported higher levels of dissociation during the assault perceived their memories to be more fragmented when interviewed by police and that those with greater levels of memory fragmentation were more likely to feel that they had given an incoherent account of what happened. And these factors, in turn, left them less likely to proceed with the legal case.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital, and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.