The new phones that are stuck in the past

Light

LightThese sleek, downgraded cell phones are meant to promote mental wellbeing – by turning the clock back to the pre-smartphone era.

It was back in 2008 when Norwegian entrepreneur Petter Neby and his stepdaughter first realised they had a problem. Their cell phones were getting in the way of their relationship. They stared at their screens during dinner, before bed and lounging around home.

It was an addiction they couldn’t break, almost like eating chocolate, Neby thought. Eventually, he knew he needed to reconnect to his stepdaughter without the filter of technology.

“How can I put the delicious chocolate in the refrigerator?” he said. “If it’s out, I will eat it all.”

After several years of tinkering, Neby invented the solution to his mobile obsession: another cell phone. But unlike his Blackberry, this one was specifically designed to promote healthy behaviour by being used as little as possible. With this idea in mind, Neby’s company Punkt was born.

You might also like:

It now stands as one of several start-ups aimed at tempering advanced technologies with a return to good old-fashioned humanity, providing an escape route from the anxiety and addiction of smartphones. Because these secondary devices do little more than make calls, owners say they have rediscovered the freedom they had before their iPhones were surgically attached to their palms.

Researchers are split on the supposed benefits, and whether the phones truly have the power to change deeply rooted behaviours and cognitive processes for the better. While they separate the facts from the fiction, a niche group of supporters feel that they’ve found tech salvation.

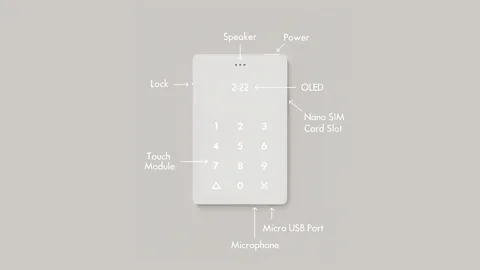

It all begins with the design. The Light Phone, created in 2015 by Joe Hollier and Kaiwei Tang in New York, is reminiscent of the ominous monoliths in 2001: A Space Odyssey. The smooth rectangular slab has no external keys, camera, apps or screen. Instead, light is projected through a translucent panel to simulate a dial pad. All it can do is make and receive calls, and store nine speed-dial contacts.

Alamy

AlamyNeby’s MP-01 is a bit more complex, featuring 3D buttons and the ability to text, set alarms, connect via Bluetooth and check a calendar. The black-and-white, 2-inch (5cm) screen displays only a couple lines of text at a time.

Geke Ludden, professor of design at the University of Twente in the Netherlands, says that the devices are examples of “designs with a goal”.

“These are so simple that they don’t allow for much interaction,” she says. “You won’t use it as much.”

Thomas van Rompay of Twente believes their stripped-down style is what can make them truly effective at changing the behaviour of their users. The iPhone’s constant buzzing and notifications are the reasons people pick them up so often, he says. “The iPhone is much more an agent in itself, because it continuously attracts your attention.”

A cycle of dependence can form simply by responding to these stimuli again and again. Because the MP-01 and Light Phone are virtually incapable of displaying any notifications other than an incoming call or text, owners will naturally be less prone to touching them, he says.

This doesn’t necessarily mean the rush of dopamine we get when receiving notifications will go away, however. Peter Bloch, a former professor of marketing from the University of Missouri, says products like cell phones can be “non-functionally oriented”. This means that although they serve little to no practical purpose – like a work of art or, in this case, a nearly useless rectangle of the future – just looking at them can bring a significant emotional payoff.

“It’s not doing anything for you, but it still gives you a good feeling,” Bloch says (and he is a man who purchased his home simply because he loved its Art Deco doorknobs). He says feelings like these, ones that inspire distinct changes in behaviour, are a psychological reaction triggered when we interact with a new product.

Punkt

PunktIn a 1995 article published in the Journal of Marketing, Bloch outlined the two components that function together to create a unique mental reaction. The “cognitive” half assesses the product by comparing it to similar products in its category. It’s what you believe about a device and what it offers. The “affective” response, on the other hand, is how the product makes you feel and react. For some, this might be the swell in their chest if they slid into the driver’s seat of a factory-fresh sports car.

Bloch says the psychological responses to the aesthetic designs of the MP-01 and Light Phone, however, might actually work against the idea of using them sparingly.

“It doesn’t shout ‘emergency’ or ‘safety’ phone. There’s maybe even a fascination factor to it,” he says. “Is it too beautiful to put away?”

Hollier happily welcomes this dichotomy and its sceptics. When he was pitching the earliest Light Phone prototypes using a simple piece of plastic with a photoshopped image on top, he revelled in the emotional responses he received.

“It was able to create these very polarising and interesting conversations,” he says. “People either loved it and got it, or they really really hated it.” This polarisation, in fact, is what helped propel the idea further.

Light, whose funding initially came from a Kickstarter campaign, sold around 11,000 devices to over 50 countries its first year. Punkt sells anywhere from 50,000 to 100,000 pieces per year. (This includes the MP-01, as well as a small collection of other consumer electronics like alarm clocks and extension sockets.)

The appealing visual aesthetic of these devices is hard to ignore. Their interesting shapes and greyscale colour palettes are certainly easy on the eyes. Neby says this reaction is exactly what he and his company want to elicit.

“Good product designs are reflecting the core value of the product itself and the purpose it serves,” he says.

Light

LightRompay calls the act of buying a phone like this a quest for belonging, one that companies like Apple or Samsung can’t fabricate with their own mass-produced products. Almost more important than the functionality of the device is the self-image that comes with it.

“People surround themselves with the things that they want to belong to, that they want their identity to be,” Rompay says. “They buy these phones because they want to be seen as the person who doesn’t use the smartphone all the time.”

Even though he calls himself a critic, Bloch admits that Light and Punkt have carved out a true identity for themselves in the mobile device world. He says it fits neatly inside the spectrum of something called the “need for uniqueness”.

Regardless of background or preference, we each have an innate desire to stand out from the crowd in some way. If you feel so unique that you can’t relate to those around you, it’s a bad feeling. On the other hand, if you’re in the Royal Marines and made to look exactly the same as the rest of your unit, your need to feel unique won’t be met. These phones, Bloch says, have found a happy middle point.

They give users enough aesthetic divergence from normal smartphones to stand out, while still retaining the necessary similarities to make the devices feel grounded and approachable. The result is a state of pleasant psychological satisfaction, he says.

An attempt to grasp an exciting new identity, or a bid to create a more mindful relationship with technology? Either way, media theorist Douglas Rushkoff thinks it’s a step in the right direction.

“I do think it’s healthy that people are longing for less. That people are saying ‘enough’.”

Rushkoff believes the phones’ supporters are reacting to a phenomenon he calls “present shock”. The overload of notifications, messages and stimuli on modern smartphones have made us feel as if we’re constantly scrambling to catch up with the present moment, he says. Before now, the only people that were interrupted this frequently and incessantly were emergency call operators. “It’s a real-time, always-on existence without any sense of beginning, middle or an end. It’s just now.” People are turning to phones like the Punkt and Light to stop these constant interruptions.

“People are becoming aware that there’s something of value that gets sacrificed when you’re living at the mercy of all these apps,” he said. “It’s a crude but effective way of minimising those interruptions, and a way of representing something else.”

Alamy

Alamy“It’s kind of ironic the way to express ‘I’ve had enough’ is by buying something else,” says Ruskoff. “It’s anti-consumerist even though it’s buying something. I would rather see people disabling features on their phones.”

Bloch finds the consumerist approach somewhat ironic. “The fact that you can even buy a phone for this purpose means you’re more affluent in general,” he says. “You don’t have self-discipline.”

A growing number of A-list celebrities have been caught with their own downgraded cell phones. Kim Kardashian, Rihanna, Anna Wintour, Daniel Day-Lewis and Warren Buffet have all, at one time or another, traded their smartphones for a cheap and basic alternative.

Bloch is critical of the supposed psychological benefits of owning one of Neby and Hollier’s devices. Forcing yourself to rough it without any of the apps and features you depend on might actually create more anxiety than it takes away.

“I don’t know if we can put the genie back in the bottle.”

The central problem we’re faced with today both as humans and tech users, Rushkoff says, is the conflation of chronos and kairos, ancient Greek terms that describe two different methods of timekeeping. Chronos is the standard time, the minutes and hours that society follows and lives by. Kairos is human time, an internal concept to us that can’t be broken into any distinct measurement.

Alamy

AlamyRushkoff says kairos time is a type of biological, ever-changing clock affected by natural events like the seasons, day and night, the weather and people’s own emotional states. Modern smartphone technology, the kind that pulls us headlong into the world of chronos time, interferes with the rhythms of kairos.

Loosening the grip on people’s smartphones is tough, Hollier says. But the growing pains of relearning how to live a disconnected lifestyle are part of his efforts to change societal behaviour and psychological health at large. Sometimes that change is sweeping and visible. Other times, he says, it’s a much more intimate experience.

“If you go to the bathroom and pull out your phone, and laugh at yourself, that’s a mini-success.”

--

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital, and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

The rising market in low-tech phones