Cave rescue: The dangerous diseases lurking underground

Getty Images

Getty ImagesDoctors have placed the Thai cave boys in quarantine due to the infectious organisms they may have faced underground. So, which diseases could they have been exposed to, and how serious are they?

It’s over. Against all odds, 12 boys and their football coach have dived, waded, climbed, and walked their way out of Tham Luang cave, a sprawling labyrinth of underground tunnels that has kept them prisoner for the last 17 days.

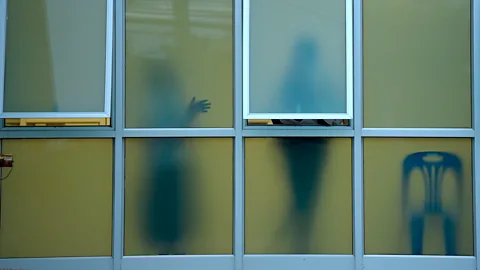

They’ve been taken to the nearby Chiang Rai hospital to recover – but the reunion with their parents will have to wait.

For now the football team is being kept in a sterile isolation room, where the only contact they’re allowed with the outside world is through a glass barrier. Their families have been told that hugging and touching are strictly-off limits while the boys undergo tests. Even if they’re given the all-clear, the first meeting will be at a distance of two metres and their parents will have to wear protective suits. Why are doctors taking such apparently extreme precautions?

You might also like:

Though thousands of visitors flock to the Tham Luang system every year, marvelling at the cavernous entrance, the stalactites that hang like icicles from the ceiling and the heavenly sunbeams which light up a giant statue of Buddha every morning, it’s likely that there are less pleasant curiosities lurking deep inside the cave. Tropical caves are hotspots for potentially deadly infections.

EPA

EPAThese caves are home to a surprising abundance of wildlife, from birds and bats to rats, which can carry microbes, including rabies, Marburg virus and obscure fungal pathogens. As you go deeper, caves become lost worlds of venomous spiders, millipedes and scorpions. The ticks that feed on them carry “cave fever”, a rare disease that is also sometimes caught in abandoned buildings.

Killer bees

“Oh yes, we see a lot of creatures,” says Rick Murcar, who is president of the National Association for Cave Diving, an organisation based in the US dedicated to improving the safety of underwater exploration in caves. “I’ve been in Mexico, for example, where one of the caves we explored had African killer bees making their hives in there, we had bats, scorpions and everything – and this is just at the entrance. The bacteria are always at the back of your mind.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThen there’s the water. The walls of limestone caves constantly seep moisture from above. This is how they form in the first place – as water drips in through cracks, it dissolves the rock underneath to leave a gap. This constant saturation, combined with the limited air supply, means the humidity of some caves is close to 100%. In caves inhabited by bats, the air is thick with pathogenic fungi, while at the bottom, a sludge of water, mud and animal guano provide a luxurious home for bacteria and parasites.

Finally, caves are dark – so dark, in fact, that that many cave-dwelling creatures have given up their eyes altogether. Astronauts are sometimes taken into caves to help them prepare for the disorientating life they will have in space. In these conditions, even with a torch, it’s easy to get cut while navigating through jagged surfaces and narrow passageways.

“I’m sure the Thai boys would have picked up histoplasmosis,” says Hazel Barton, a cave diver and expert on cave microbiology. “They’re in a tropical region in a cave that has bats in it, so there’s a high likelihood they contracted that.”

Histoplasmosis is caused by a fungus found in the droppings of birds and bats, mostly in humid areas. It can usually be treated with a course of antifungal medication, which has to be taken for several months, and possibly up to a year. It kills around one in 20 children and roughly 8% of adults who are infected. It is particularly problematic for those who are already weak or immunocompromised.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesEarlier this year, a team of doctors reported the death of a 53-year old man who arrived at a hospital in Florida with a fever, shortness of breath and a cough. He had been living in Costa Rica, but after several days of medical tests, during which he was checked for every tropical disease the team could think of, they were stumped. Eventually they discovered his passion for cave diving and “spelunking” – exploring caves – and tested him for histoplasmosis. Sadly he died on his fourth day in hospital, just before test results confirmed the diagnosis.

Bat guano

Unfortunately, histoplasmosis is extremely easy to catch, as Barton discovered first-hand last year when she took her husband caving in the US. “We walk in and I get a huge whiff of bat guano and I’m like ‘Oh no, we’re in a histo[plasmosis] cave’ and he’s like ‘histo, what’s that?’. We ended up putting a headscarf around his mouth so he didn’t inhale anything, but he still ended up getting it about 10 days later.”

Another microbe that often hides in caves is the corkscrew-shaped bacteria Leptospira. It’s spread in bodily fluids like urine from rodents and is usually caught after contact with contaminated water, where it may sneak in to the body through cuts on the skin, or through the mouth, nose, eyes, or lungs.

It causes Weil’s disease, which starts as a mild, flu-like illness. In 5-15% of cases it develops into something more serious, with symptoms that include internal haemorrhaging and organ failure. Ultimately it can be fatal. This bacterium has a history of infecting cavers. In 2005, a man was infected in Sarawak, Malaysia, even though he was already on antibiotics.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHowever, the sickness the rescued Thai boys are most at risk of is melioidosis. This emerging infection is found across the tropics, from Southeast Asia to Northern Australia. It’s thought to affect around 165,000 people every year, of which roughly half – 89,000 – die.

The disease presents a number of problems. It’s caused by a bacterium that lives in soil, and can be caught from everyday activities such as rice farming. Diagnosis is notoriously tricky, since the disease can manifest as a wide range of symptoms – from coughs to fevers, which are also hallmarks of infection by many other microbes. It’s also naturally resistant to a wide range of antibiotics.

In Thailand, the rescued football team is currently undergoing blood tests that will reveal if they have been exposed. They wouldn’t necessarily have symptoms yet, since these can take up to 21 days to appear. But if they are found to have been infected, they may still have a good chance of recovery. Rapid treatment of melioidosis is crucial, and the boys have reportedly already been taking antibiotics for several days, although it’s not clear which kind or what for.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFor anyone thinking of exploring a cave, however, there are simple precautions you can take to protect yourself against the dangerous infections that lurk within. Even just wearing rubber boots can prevent bacteria from getting on your skin as you walk through water that may contain guano.

“After a dive the trick then becomes you have to get undressed,” says Murcar. “You might have a rinse station where you can pour water down from a jug onto boots and things like that.”

Barton is keen to point out that not all caves are microbial death traps. It all depends on where they’re located and what lives inside.

“Most of the caves that we [the Cave Science group at The University of Akron, Ohio] study are some of the cleanest environments on Earth,” she says. “Some have lower cell numbers than ancient ice found in Antarctica. The Thai boys were in a flooding cave in a tropical region, where a lot of the potential for disease would have been picked up by water on its way into the cave.”

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital, and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.