The salvagers who raise World War Two tanks from the dead

Anton Skyba

Anton SkybaTitanic tank battles were once fought on what is now Belarus. Now, a dedicated team of salvagers scour marsh and forest to find these forgotten reminders of World War Two.

BBC Future has brought you in-depth and rigorous stories to help you navigate the current pandemic, but we know that’s not all you want to read. So now we’re dedicating a series to help you escape. We’ll be revisiting our most popular features from the last three years in our Lockdown Longreads.

You’ll find everything from the story about the world’s greatest space mission to the truth about whether our cats really love us, the epic hunt to bring illegal fishermen to justice and the small team which brings long-buried World War Two tanks back to life. What you won’t find is any reference to, well, you-know-what. Enjoy.

When the German army attacked the Soviet Union in the summer of 1941, tanks were a crucial factor in their initial success. German tanks roared across the Soviet border giving the enemy no time to recover.

As the Soviets reeled under the surprise attack, the most powerful German formations swept through what is now Belarus. Huge battles were fought, leaving the land strewn with dead bodies and ruined machines.

Now, more than 75 years after the fighting, both Soviet and German tanks are being lifted from the marshes in Belarus. One Belarusian family has been looking for tanks littered all over the country’s vast marshes and restoring them. With photographer Anton Skyba, I was able to witness one heavy Soviet tank, a KV-1, being restored after its recovery – and its participation in a re-enactment of a World War Two battle.

The family, the Yakushevs are the most famous “tank-hunters” in Belarus.

You might also like:

Some years ago Vladimir Yakushev worked as a collective farm engineer. One day, some people asked him to find and lift up a BT-7 tank, that had been stuck in the marshes since 1942.

Older locals said the vehicle had sunk into soft ground near a spring, but nobody knew the exact location. Vladimir suggested that the tank had been blocking the spring and the water had found a new route. He was absolutely right – the BT-7 was discovered 10 metres (33ft) away from the current spring.

Anton Skyba

Anton SkybaThis was almost 20 years ago. Since then, Vladimir and his sons have taken dozens of armoured vehicles and almost every one has been restored to working condition. Now Vladimir works as the chief mechanic and renovator in a historic and cultural complex called the ‘Stalin Line’ near the country’s capital, Minsk.

Both of his sons, Aleksei and Maxim have been working together with their father in the museum’s hangar. The Yakushevs use a rotation scheme. They work and live on the museum’s territory for nine days and then take a 270km (168 miles) trip home to their native village and stay there for five days.

The family has a small flat with a kitchen and a big common room with beds while they are based in the workshops.

Denis Aldokhin

Denis Aldokhin“There was the time when we slept in vans,” says Vladimir, who has been commuting from Stalin line to his home village for nine years. One son joined him in 2010, and the other in 2012.

The Yakushevs are not the only tank hunters in Belarus. Other amateurs also search for the lost vehicles. However, recovering such finds is time-consuming and the license for searching and recovering military equipment is only issued personally by the country’s president, Alexander Lukashenko.

Only two teams have such a licence. The Yakushev family and a specialist in renovation, Alexander Mikalutski, are the first. The second team, an amateurs club called Poisk, which is where Vladimir and Mikalutski started to learn their trade almost 20 years ago.

“From the very beginning we worked without a salary. We thought, we would lift up tanks, renovate them and get money for this. But we had worked in Poisk for nine years and only received a salary for one year. I was growing potatoes, cucumbers, and selling them to make money for living,” says Vladimir.

Now the team works for an official fixed salary. The hobby has turned into their job, but the work itself feels like a holiday.

Anton Skyba

Anton Skyba“When you have a good job, you don’t need holidays,” they joke. “We want to create.”

The main object of these tank hunts is the armoured vehicles that became mired in marshes, many of which fell off bridges into the soft ground. Those that slipped underneath the water were preserved. Tanks, even when set on fire by enemy guns (known as “brewed up” by tank crews), were seldom abandoned. If it was possible to lift up and fix it, it was removed by a maintenance battalion. The Germans were especially good at it. If they could not pull out the tank, it was filled with explosives and destroyed to stop it falling into enemy hands.

“We raised two brewed-up Panzers 38(t)s, and a German StuG III self-propelled gun [a tank-like vehicle with an artillery gun], all of them piece-by-piece,” say the renovators. Throughout this period, the hunters lifted up only five tanks that were intact. “Almost intact,” Vladimir says. “We put new turrets on them.”

Often they have to assemble a working model made up of pieces from several tanks. One Czech vehicle, now at the history of engineering in Tolyatti in Russia, was built from three separate vehicles.

The crew collect data for months before they raise a tank. They find help in archives and from older residents, some of whom were children during the war. Then they wander through forests and marshes searching for machines.

Denis Aldokhin

Denis AldokhinVladimir has the most experience of walking through the mire. When it is very deep they put on chemical protection suits. They use metal detectors and feel into the mire with special 8m-long (26ft) probes.

“It is easy to hunt when you are shown a definite point,” says Mikalutski. “But to get to the point you may have to go five kilometres through marshes or snow. You reach the place and then you have to crawl back...”

For the sake of their own safety, the tank hunters never go into the marshes alone.

They often spend nights near the marshes in a van. “The strongest frost we have ever had when sleeping in a van is -33C. You used to come, change clothes and hide inside your house on wheels,” says Vladimir.

Denis Aldokhin

Denis AldokhinThere is a different problem in the summer. “What a buzz it is at night. It seems mosquitoes will overturn the van.”

Insect repellents do not help in marshes. The conditions are extremely difficult in hot weather: they have to work in thick jackets and hats even when it is 30C because of clouds of insects.

When a tank is being lifted up, the officers from the Ministry of Internal Affairs arrive, take the ammunition, and seal off the area so that nobody has “their head shot off”. The Ministry of Emergency Response officers drain the area the tank is stuck in. Then there are mine clearers sent by the Ministry of Defence; they clear the area of mines, while ammunition is removed and destroyed.

“It has never exploded,” says Vladimir, as he superstitiously knocks on wood three times.

Anton Skyba

Anton SkybaLater, a tank is hooked by steel hawsers and pulled by a large lorry. One example, a KV-1, was lifted up in November 2015 near Senno, in the Vitebsk region of Belarus. The KV-1 got stuck there in July 1941, when one of the biggest tank battles of the Second World War took place. The battle involved about 2,000 tanks from both sides, including this KV-1.

After a long fight, the Soviet forces had to retreat, with tanks ordered to drive through the forests to avoid air attack. This 47-tonne jumbo became stuck in a swamp.

'The Iron Roadblock'

The tank that helped save the Soviet Union

The KV-1 was a well-regarded vehicle, almost impervious to anti-tank weapons of the day; and it was armed with a powerful 76mm gun that could knock out any tank in German service.

When the Germans invaded in June 1941, KV-1s had only just entered service, and came as a huge shock to German tank crews.

In one incident in Lithuania June 1941, a single KV-1 held up an a Panzer division for an entire day.

The Germans were so impressed with the KV-1 they nicknamed it “the iron roadblock”.

It is not just shells that see the light of day. Chocolate, hair brushes, and other personal items are found. Vladimir Yakushev recollects a unique discovery when they recovered a German Panzer III medium tank which fell into swamps in Vitebsk region.

“The tank was absolutely new, it ran only 400km. The crew was leaving it in a hurry, all things were left in their places.” A pair of binoculars, socks, textbooks on agronomy (plant sciences) and accounting were all found in the upended tank. It seems that the Germans were sure that they would conquer the USSR and were already making plans for after the conflict.

Anton Skyba

Anton SkybaA parcel to one of the tankmen from Germany was discovered in the tank. Inside there were Soviet hair brushes and shaving razors.

“We even ate the German chocolate from this tank,” says Mikalutski. Now the renovated tank is in the Belarusian State Museum of the Great Patriotic War in Minsk.

One tank, Vladimir says, was found with its entire crew still inside it. The bones were taken away to the Belarussian Ministry of Defense.

It has always been easier to lift up tanks than to restore them. During the war, tank-building made a giant leap both in the USSR and in Germany, with much less time between initial designs and construction. Sometimes tanks entered production too early; when the Soviet T-34 was rushed into production in 1941, more than 800 corrections had to be made to the design by the end of the year, some of them requiring entirely new parts. When renovators assemble one complete tank from several machines it can turn into quite the puzzle.

Anton Skyba

Anton Skyba“You take the idle sprocket front jockey wheel from a T-34 launched in 1942 to put it on the model launched in 1941. But it doesn’t match,” says Vladimir.

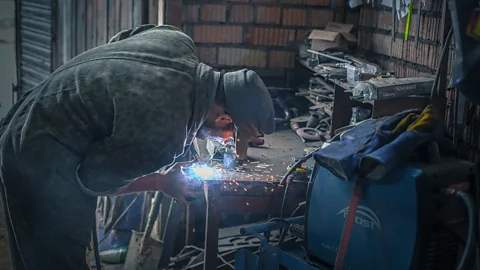

Sometimes, he is the only person who knows how to fix a spare part or understand why the tank won’t start. Vladimir was trained as mechanic. In order to help his father, his son Maxim became a welder and Aleksei a painter. Mikalutski is a former marine engineer, who worked in the navy search and rescue service for eight years.

Not all tanks are built the same. “If you want to change one spare part in a German tank you have to dismantle half of the machine,” says Vladimir. “Soviet tanks were made to be assembled and fixed fast, because in the war time even children were welding such machines.” The restoration team claims that some hulls they found were clearly made by children.

The KV-1 that they found needed five months of restoration.

The state military and industrial committee donated a self-propelled gun with similar parts, and the Belarussian Railways presented a traction engine converted from a self-propelled gun. These machines became the donors for the tank.

Now the KV-1 differs from an original vehicle in only a handful of parts.

Anton Skyba

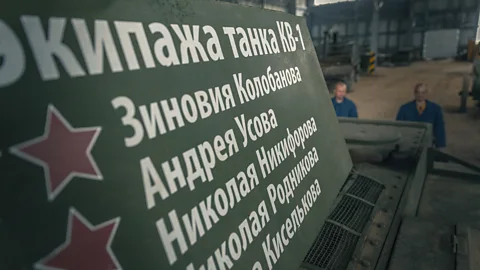

Anton SkybaThe KV-1 was feared by the Germans because its armour was too thick for their standard shells. In August 1941 the crew of the Soviet tank commander Kolobanov in a KV-1 knocked out 22 German tanks within 30 minutes after setting an ambush near the city of Leningrad. The KV-1 we have followed in this story was restored to help mark the 75th anniversary of Kolobanov’s battle.

Where do these tanks go, after they have been restored? Some of them settle on plinths as monuments (practically every Belarusian town has one), while some become museum exhibits in Belarus or Russia. It is not easy to sell them abroad. Not every fighting machine can be sold. The sales permit is only issued if there are more than two examples in the country. The BT-7 the team helped bring back to life is the only working specimen in the world. “It works, runs. On the wheels it can go 70km/h and on its tracks 55km/h,” says Vladimir. At the time it was built [1935] it was the fastest tank. It could fly across bridges.”

When working for the club, they sold a German armored vehicle, an SdKfz 252, to a collector in Britain, and a Soviet heavy tank IS-2 went to a private collection in Latvia. This did not make the renovators rich. Vladimir drives an old Soviet Niva four-by-four. Occasionally they have to fix the car with their own hands; fortunately, they are very good at welding.

The biggest number of tanks are left in the Stalin Line museum complex. Working models live in the repair hangar. When they are not gathering dust they are participating in parades or filming. The developers of the computer game World of Tanks have even visited to record the sounds of different tanks.

***

At least 15 times a year the complex, having built up a collection of working machines from the Second World War, shows battles re-enactments.

The restored KV-1 leaves the hangar to take part in a re-enactment. The team of renovators put on helmets and turn into the tank crew. They take part in the show, too.

Anton Skyba

Anton Skyba“At first we always drive the last restored tank, break it in,” they say. “We do not trust the machine to the others: if they burn the engine clutch, it turns into a monument.”

The performance in the open air shows an episode from the life of a Belarusian village during World War Two. This event is a reenactment of Operation Bagration in 1944, which saw the liberation of what is now Belarus.

Tanks are roaring and shooting, though thankfully all the ammunition is blank.

After the re-enactment, the renovated tank is washed.

Anton Skyba

Anton SkybaToday the KV-1 has pretended to destroy two German tanks, a Panzer III and Panzer 38(t). But the tank renovators do not play favourites. “All our tanks are our favourites, even the German ones,” says Mikalutski.

“Earlier we restored mainly Soviet machines but as the re-enactments started, German tanks became necessary. To find and make a ‘German’ is such joy," he says. “When a machine leaves the workshop, a tear of happiness drops on the metal.”

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital, and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.