The ‘disaster psychologists’ who helped after Mexico’s quake

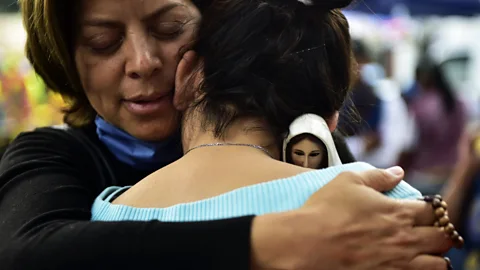

AFP/Getty Images

AFP/Getty ImagesAs Mexico reeled after last week’s magnitude 7.1 earthquake, it wasn’t just rescue workers and doctors who mobilised fast. Julissa Trevino reports from Mexico City.

Raquel Barrera felt nauseous and couldn't sleep or eat.

“I felt dizzy, too. I was scared it was going to happen again,” she said.

Last week, 12-year-old Barrera had been caught in the middle of the magnitude 7.1 earthquake that hit central Mexico, killing hundreds of people and toppling many buildings. Barrera was in class at her middle school when the earthquake struck at just past 13:00 on 19 September. Her mother, Eucevia Roman, had been waiting outside to pick her up.

Her symptoms – nausea, insomnia and a loss of appetite – didn’t require medical attention. However, in the days following the quake, the young girl’s parents decided to seek help, after hearing doctors were seeing patients affected by the disaster at a government building in downtown Xochimilco, one of Mexico City’s hardest-hit districts. The doctors referred her to a psychologist – one of many who mobilised to help the country’s children and distressed adults cope with the aftermath.

Typically, much of the mental health support that victims receive after natural disasters comes months after the event, if at all, and after basic needs are first met. But what’s changing in Mexico is that now counsellors and psychologists are moving much faster to help people immediately. Last week, hundreds of them offered free counselling in shelters at government buildings and via hotlines within hours of the quake.

The trauma of the event is likely to take a toll on many residents – not just those who lost loved ones, but people who were evacuated from buildings, felt an earthquake for the first time or remembered the devastation of the 1985 earthquake, as well as the hundreds of volunteers who rallied to help in the relief efforts. To cope with the aftermath of a disaster, survivors usually go through a process of disbelief, bewilderment, difficulty focusing, denial, anxiety, fear and eventually depression and sadness, according to researchers.

Yet if the world can learn from what happened in Mexico last week, it’s that intervening faster to offer immediate mental health assistance may be key to helping people deal with trauma in the longer-term – and particularly for children like Barrera.

Julissa Trevino

Julissa TrevinoJust steps from the building where Barrera had gone for a checkup, she met Adriana Chavez, a psychologist with the Women’s Institute of Mexico City, a government organisation that supports the health and safety of women in the city. The group had set up a canopy there to offer one-on-one sessions with victims of the earthquake.

“She’s dealing with symptoms of post-traumatic stress as a result of the natural disaster,” according to Chavez. “We want people to understand what these concepts mean. This is the first time Barrera has ever experienced an earthquake, so I explained to her how an earthquake works, and what’s normal for people [to feel] after natural disasters: chaos, shock, fear. At the end of the day, we just lived through a traumatic experience.”

After meeting with Chavez, Barrera felt better. “She told me to stay away from news about the earthquake and showed me breathing exercises,” Barrera says.

The 12-year-old’s experience is a normal way of processing trauma, Chavez says, and most people will begin to feel normal by the second week. But if left untreated, people affected by disasters can develop post-traumatic stress disorder, a condition that could last months or years marked by flashbacks, an avoidance of feelings, and anxiety or depression.

Julissa Trevino

Julissa TrevinoResearch shows that up to 29% of survivors of disasters develop PTSD, and that they are significantly more likely to have a lifetime anxiety disorder and affective disorder. A survey of adults in 75 Mexico City shelters following the 1985 earthquake found that 32% were experiencing PTSD, and direct victims of the disaster reported having higher levels of anger, depression and confusion. Following the Turkey earthquake of 1999, 17% of survivors reported having suicidal thoughts.

According to research, it’s after the first few days following a disaster that mental health issues manifest and need attention.

Across town in Colonia Roma, Rosa Inez Borga, 27, sat with her four-year-old daughter, Salma, last Thursday. They were staying at a makeshift albergue, or shelter – one of 45 that had been set up – after being evacuated from their building in nearby Colonia Doctores. Salma was in kindergarten when the earthquake hit. “I was crying,” said Salma. “The teacher told us to sit down and started singing with us.”

Borga said a psychologist had come by to see Salma, mostly to play games and distract her.

There are no set rules for how to interact with children affected by disasters, says Fernando Alvarez, a coordinator for volunteer search-and-rescue group Brigada de Rescate Topos Tlatelolco, commonly known as the Topos, Spanish for moles. “Sometimes it’s just playing games, doing activities, drawing. With each child, it varies,” he said.

Julissa Trevino

Julissa TrevinoAs part of their first aid relief work, the Topos work with volunteer psychologists who help prevent post-traumatic stress among those affected, particularly children, who are one of the most vulnerable populations. A study assessing the mental health impact of the 2011 earthquake in Japan showed that “younger children and those with parents suffering from trauma-related distress were particularly vulnerable to the onset of pediatric mental disturbances.”

The Topos had recently worked in Juchitan, Oaxaca, where a magnitude 8.2 earthquake on 7 September resulted in dozens of collapsed buildings. They provided support to about 80-100 children there. They’ve also volunteered after natural disasters hit Japan, Indonesia and Haiti.

Alvarez says there is no other international group that brings psychological help as part of search-and-rescue relief efforts. Many groups simply don’t offer psychological relief. But the understanding and training of psychological first aid is gaining traction.

"We've seen that if we help at the very beginning, it really helps children avoid post-traumatic stress,” says Alvarez. “If they get the help immediately, recovery is quicker, especially among younger kids.”

He also points out that it’s more cost effective to provide preventative psychological help than to try to solve mental health problems en masse later on.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe day after the earthquake, psychology students, professors and alumni at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) gathered to volunteer. They formed brigades of teams who took shifts visiting shelters and disaster zones across the city.

“Our first aid support focuses on stabilising emotions and identifying how people can move past a traumatic experience like this,” says Silvia Morales, coordinator for training and support services at the UNAM psychology department. “It’s not that easy, especially if they’ve been hurt or lost loved ones.”

Psychological first aid offers various methods for dealing with disaster victims: it includes a slow breathing exercise to a count of three, which helps to relax and reduce anxiety, and talking them through an imagined situation. Victims could also benefit from talking through their experience of what’s happened to them or their fears, but this method requires professional help since it could trigger negative emotions.

Mental health support for those affected also changes over time, Morales says. “The immediate support is crisis intervention and helping people understand what’s happened. Later it will be helping people manage their emotional shock, grief and other post-traumatic feelings.”

About 400 volunteers have signed up through UNAM to participate in shifts. The university also has two hotlines open to provide support, with volunteers working there night and day. Francisco Martinez, who manages the helpline, said they were receiving about 100 a day.

Getty Images

Getty Images“We’ve heard a lot of calls from people who are in crisis mode. They’re anxious, wondering what’s going to happen or if there’s going to be a replica,” says Martinez. “Some people feel a shake from trucks passing the street and that triggers anxiety. Now everything draws our attention and takes us back to the earthquake. It’s fear that we won’t be safe. Our goal is to calm them down and reduce their anxiety.”

Martinez says more women have called then men, perhaps because they feel more comfortable calling in. “It has a lot to do with culture, tradition, but we want people to know we’re here. The objective of our support is the same, regardless if it’s men or women.”

There were many other efforts by experts in the week following the earthquake. Last Thursday, a psychologist's office had set up a support session for children and their families; the office said it would be the first of many. And as part of a collaboration between a clinic in Colonia Condesa and various psychology associations, another 200-300 psychologists joined brigades to visit albergues starting Saturday. Another group was supporting victims at the Enrique Rebsamen school, where they said families were angry and in shock after hearing rumours and false news reports.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMartinez says the mental health of volunteers and disaster workers would also need to be addressed in the coming weeks. In a 2007 study looking at the impact of disasters on first responders, researchers found that exposed disaster workers had significantly higher rates of ASD (acute stress reaction), PTSD and depression than their counterparts who had not assisted in the same relief work. Disaster workers with ASD were also nearly four times more likely to be depressed seven months later.

Petra Gante, 41, was another Mexico City resident still coping with the psychological aftermath days after the quake struck. “I don’t feel well since it happened,” Gante told BBC Future last week. “I’m nervous, I’m not hungry. I see all the chaos, and it makes me more anxious. It scares me to be home.”

As of 26 September, Xochimilco – a neighbourhood of Mexico City – still didn’t have running water. When she visited the Instituto de las Mujeres tent, Gante was also still waiting for an assessment on the safety of her home – a fact that worries her because while her home doesn’t appear to have any damage, the home next to hers looks like it’s leaning and could fall.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThough her family is safe, she says she constantly thinks about what might have happened. “I started remembering the one from ‘85. The ambulances, the noise,” she says. “I was nine. I started forgetting it, but this reminded me of it because we lost water and electricity then, too. That brought back memories.”

She says she intends to follow up with mental health support at the local office of the Women’s Institute of Mexico City.

A week after the earthquake, life in the city hasn’t returned to normal. Many schools haven’t yet reopened, and volunteers are still out sorting through donations and rubble. But thanks to the work by psychologists in the days since, Raquel Barrera says she’s recuperated from the post-traumatic stress symptoms she experienced. “I’m practising the exercises [Chavez] showed me,” she says. “It took a few days, but I feel fine.”

--

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital, and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.