Why the biggest challenge facing AI is an ethical one

Alamy

AlamyArtificial intelligence is touching our lives in ever more important ways - it's time for the ethicists to step in, say our panel of experts.

Grand Challenges

A guide to the issues that define our age

We may have things better than ever – but we’ve also never faced such world-changing challenges. That’s why Future Now asked 50 experts – scientists, technologists, business leaders and entrepreneurs – to name what they saw as the key challenges in their area.

The range of different responses demonstrate the richness and complexity of the modern world. Inspired by these responses, over the next month we will be publishing a series of feature articles and videos that take an in-depth look at the biggest challenges we face today.

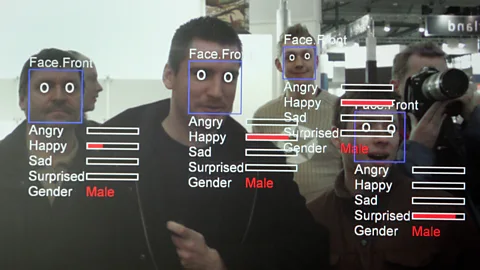

Artificial intelligence is everywhere and it’s here to stay. Most aspects of our lives are now touched by artificial intelligence in one way or another, from deciding what books or flights to buy online to whether our job applications are successful, whether we receive a bank loan, and even what treatment we receive for cancer.

All of these things – and many more – can now be determined largely automatically by complex software systems. The enormous strides AI has made in the last few years are striking – and AI has the potential to make our lives better in many ways.

In the last couple of years, the rise of artificial intelligence has been inescapable. Vast sums of money have been thrown at AI start-ups. Many existing tech companies – including the giants like Amazon, Facebook, and Microsoft - have opened new research labs. It’s not much of an exaggeration to say that software now means AI.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSome predict an upheaval as big as – or bigger – than that brought by the internet. We asked a panel of technologists what this rapidly changing world brimming with brilliant machines has in store for humans. Remarkably, nearly all of their responses centre on the question of ethics.

For Peter Norvig, director of research at Google and a pioneer of machine learning, the data-driven AI technique behind so many of its recent successes, the key issue is working out how to ensure that these new systems improve society as a whole – and not just those who control it. “Artificial intelligence has proven to be quite effective at practical tasks — from labeling photos, to understanding speech and written natural language, to helping identify diseases,” he says. “The challenge now is to make sure everyone benefits from this technology.”

The big problem is that the complexity of the software often means that it is impossible to work out exactly why an AI system does what it does. With the way today’s AI works – based on a massively successful technique known as machine learning – you can’t lift the lid and take a look at the workings. So we take it on trust. The challenge then is to come up with new ways of monitoring or auditing the very many areas in which AI now plays such a big role.

For Jonathan Zittrain, a professor of internet law at Harvard Law School, there is a danger that the increasing complexity of computer systems might prevent them from getting the scrutiny they need. “I'm concerned about the reduction of human autonomy as our systems — aided by technology — become more complex and tightly coupled,” he says. “If we ‘set it and forget it’, we may rue how a system evolves – and that there is no clear place for an ethical dimension to be considered.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIt’s a concern picked up by others on our panel. “How will we be able to certify these systems as safe?” asks Missy Cummings, director of the Human and Autonomy Lab at Duke University in North Carolina, who was one of the US Navy’s first female fighter pilots and is now a drone specialist.

AI will need oversight, but it is not yet clear how that should be done. “Presently, we have no commonly accepted approaches,” says Cummings. “And without an industry standard for testing such systems, it is difficult for these technologies to be widely implemented.”

Yet in a fast-moving world, regulatory bodies often find themselves playing catch up. In many crucial areas, such as the criminal justice system and healthcare, companies are already exploring the effectiveness of using artificial intelligence to make decisions about parole or diagnose disease. But by offloading decision-making to machines, we run the risk of losing control – who’s to say that the system is making the right call in each of these cases?

Danah Boyd, principle researcher at Microsoft Research, says there are serious questions about the values that are being written into such systems – and who is ultimately responsible for them. “There is increasing desire by regulators, civil society, and social theorists to see these technologies be fair and ethical, but these concepts are fuzzy at best,” she says.

One area fraught with ethical issues is the workplace. AI will let robots do more complicated jobs and displace more human workers. For example, China’s Foxconn Technology Group, which supplies Apple and Samsung, has announced it aims to replace 60,000 factory workers with robots, and Ford’s factory in Cologne, Germany puts robots right on the floor alongside humans.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhat’s more, if increasing automation has a big impact on employment it could have a knock-on effect on people’s mental health. “If you look at what gives people meaning in their lives, it’s three things: meaningful relationships, passionate interests, and meaningful work,” says Ezekiel Emanuel, a bioethicist and former healthcare adviser to Barack Obama. “Meaningful work is a very important element of someone’s identity.” He says that in regions where jobs have been lost when factories close down can face increased risk of suicide, substance abuse and depression.

The upshot is that we could see a demand for more ethicists. “Companies are going to follow their market incentives – that’s not a bad thing, but we can’t rely on them just to be ethical for the sake of it,” says Kate Darling, who specialises in law and ethics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. “It helps to have regulation in place. We’ve seen this in privacy, or whenever we have a new technology, and we figure out how to deal with it.”

Darling points out that many big-name companies, like Google, already have ethics boards in place to monitor the development and deployment of their AI. There’s an argument that it should be more common. “We don’t want to stifle innovation but it might get to the point where we might want to create some structures,” she says.

The details of who sits on Google’s ethics board and what it actually does remain scarce. But last September, Facebook, Google, and Amazon launched a consortium that aims to develop solutions to the jungle of pitfalls related to safety and privacy AI poses. And OpenAI is an organization dedicated to developing and promoting open-source AI for the good of all. “It's important that machine learning be researched openly and spread via open publications and open-source code, so we can all share in the rewards,” says Google’s Norvig.

If we are to develop industry and ethical standards and get a full understanding of what’s at stake, then creating a braintrust of ethicists, technologists and corporate leaders will be important. It’s a question of harnessing AI to make humans better at what we already do best. “Our work is less to worry about a science fiction robot takeover and more to see how technology can be used to help with human reflection and decision-making, rather than to entirely substitute for it,” says Zittrain.

Keep up to date with Future Now stories by joining our 800,000+ fans on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital, and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.