Virtual reality: The hype, the problems and the promise

Nan Palmero/Flickr/CC BY 2.0

Nan Palmero/Flickr/CC BY 2.0It’s the technology that is supposed to be 2016’s big thing, but what iteration of VR will actually catch on, and what’s just a fad? Tim Maughan takes an in-depth look.

I’m sitting in the dark. It’s pitch black, apart from a circular spot of light on the wall in front of me. Voices emerge, a woman and a small girl, as shadow puppets cast by unseen hands play out stories in the torchlight. Somewhere above me is a low, ominous boom.

The girl becomes scared. The woman, her mother, tries to calm her. She tells her the sound is just a giant walking around the city above us – the same giant that has accidentally knocked out the power lines and plunged us into darkness.

Lights come on, and I can finally see where I am: in a basement, surrounded by the mundane fragments of everyday life – boxes, paint cans, chairs, old toys. Near me lies a copy of Time magazine, with the headline IS THIS WAR?. The date is March, 2017. I hear more booms from the city above.

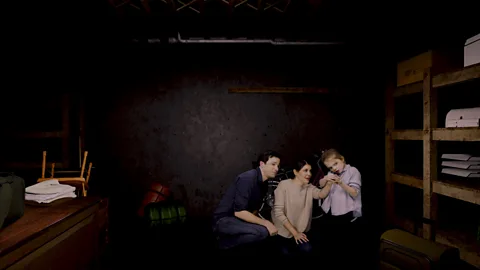

Milica Zec/Winslow Porter

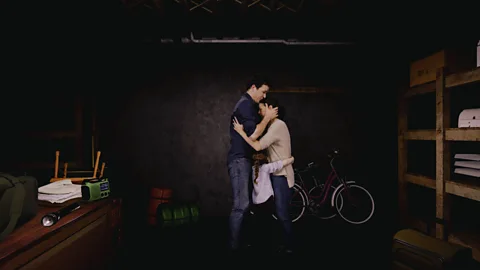

Milica Zec/Winslow PorterMy attention is drawn back to the mother and child – they’ve been joined by a man. The father, presumably. They look like the archetypal middle class, white American family – but it’s clear something is wrong. He has just returned from the surface, visibly shaken by what he’s seen. The adults hug each other, attempting to keep their daughter, and themselves, calm. From somewhere in the distance comes the familiar, spine-chilling sound of an air raid siren, as the booming sounds draw closer. They become deafening, and I glance up just in time to see the ceiling falling in on top of me, before I’m plunged into darkness again…

I pull the virtual reality headset from my face. For a fraction of a second I’m not sure where I am, before my eyes adjust to the light and I remember that I’m sat in a studio space in the New Inc building on the Bowery in New York. I’ve just experienced Giant, a virtual reality short story.

Despite the fact that the vast majority of people have still never used it, it seems impossible to avoid talk of VR this year. News articles, trend watchers, and technology evangelists are constantly telling us that 2016 is the year that it will finally arrive. Samsung, HTC and Sony are launching their own VR headsets. So are Facebook and Google. It’s going to revolutionise watching movies and playing games, we are told. Social media will never be the same. All your dreams will come true – in time you’ll be able to recreate any human experience you can imagine, or delve into adventures straight out of Hollywood blockbusters, all from the comfort of your sofa.

It’s an unstoppable hype machine that, for me personally, culminated in Versions 2016 – a one-day, $700-a-ticket conference in New York that aimed to bring together artists, technologists, and investors to discuss VR’s potential. It was an interesting day of talks – more thoughtful, critical, and honest than I had expected – which left me more interested in the people on the stage and behind the headsets than the technology itself. Who are these people investing their money, creativity, and careers in this new technology? And how do they intend to profit from VR’s promise, navigate the hype, and avoid its current limitations?

Virtual origins

The tag line for Giant is ‘a virtual reality experience inspired by real events’, as it draws on the childhood memories of one of its creators, 34-year-old Milica Zec, who sheltered with her family from Nato bombing raids in war-torn Serbia in the 1990s. She explains to me that the decision to set Giant in what appears to be contemporary New York was taken to heighten the emotional experience of the piece. “The reason we decided to go with an American family is because usually when we read about conflict, it’s never happening to Westerners. Westerners always think, ‘that cannot happen to us’. Therefore, it's hard to identify with the victims, but if someone looks like you, dresses and speaks like you, you can identify better. We were hoping maybe people can feel more if it looks like a mirror of your own family.”

Milica Zec/Winslow Porter

Milica Zec/Winslow PorterFor Zec this is one of VR’s most promising potentials – to be able to drop audiences into a situation and force them to react emotionally, in ways that traditional filmmaking or journalism might struggle to do. “We really cannot understand what the people [in Syria and other places] right now are going through, so I thought maybe if we put the viewer inside the shoes of the family, or near them, maybe they can feel more and understand more rather than just reading a headline in a newspaper.”

It’s a worthy aim, but I’m not sure how convinced I am. While Giant is certainly compelling, unique, and well-crafted, I didn’t feel particularly emotionally attached to the family. It felt very much like I was just sat on a chair, watching what was happening to them over in the other corner of the basement; they were oblivious to me, like I was still the invisible audience watching a stage play rather than caught up in the action itself. But perhaps I’m in the minority – Zec and her co-creator Winslow Porter had just returned from the Cannes Film Festival, where Giant had made quite an impact amongst traditional filmmakers. “They watched it and they said, ‘Wow, you guys managed to achieve [an emotional intensity] in five minutes what would usually take us 20 minutes.’”

Porter had worked on VR projects before Giant, but for Zec – who comes from a traditional filmmaking background – it was her first experience of working in the medium. “Everything is different,” she says about making the transition. “Forget everything you know about film and learn VR from scratch.” The film was made in a similar way to how special effects-heavy Hollywood blockbusters are put together – the actors were shot against a green screen, and then the virtual set of the basement was modelled on computer, and animated using a video games engine. It’s an intensive process, getting everything to come together. “One day of shoot, four months of post production,” she tells me.

The two are currently residents at New Inc, an incubator project run by New York’s New Museum that helps artists working with technology to change their ideas into a business. Next, they hope to build careers in VR. It sounds potentially risky to me, and I ask them if they’re worried that VR won’t catch on. Porter doesn’t think that’s likely, and is convinced that VR will be a success in the long run. “I’m not worried because I know that it’s coming… It might not be at the rate that some people are hyping, but I don’t think as artists we’re hyping it ourselves. We're just trying to create it.”

Milica Zec/Winslow Porter

Milica Zec/Winslow PorterJust as I’m finishing off my interview an elderly couple, presumably patrons of the New Museum, arrive in the studio space as part of a tour of New Inc. Seemingly wealthy and well dressed in a stereotypically Manhattan way, they’re introduced to Zec and Porter before the woman straps the headset on to experience Giant for herself.

When she’s finished she pulls the headset off, blinking as she readjusts to the brightly lit studio. I ask her what she thought. “I’ve never done 3D like that,” she says, her eyes wide. “I’ve never been in virtual reality before. It was very realistic when the ceiling came down, the black explosion. You don’t know where you start or where you end. The environment was very realistic. You’re in. You’re really in it. It’s claustrophobic in a way, but they feel claustrophobia, I guess, because they’re being trapped. It’s much more realistic than being in a movie theatre. It’s around you and you’re really in it. Oh gosh.”

Zec and Porter beam happily; it’s the exact response they’re hoping for.

***

I’m stood in what appears to be the foyer of a large building, perhaps a conference centre. I’m surrounded by glass and steel architecture. As I glance around I see a few people, all wearing Google t-shirts, backing away from me.

And then there’s a sudden deluge of people, hundreds of bodies pouring out of a corridor, surrounding me. Faces peer in close at mine. Smartphones are held up, snapping photos. Apart from looking up at the ceiling or down at the floor it’s impossible to avoid the inquisitive, prying stares. It’s claustrophobic – both intimidating and strangely exhilarating, like how it must feel to be a celebrity, mobbed by fans.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesI pull the virtual reality headset from my face. For a fraction of a second I’m not sure where I am, before my eyes adjust to the light and I remember that I’m in a sparse, modern meeting room in Google’s New York YouTube offices. I’ve just experienced footage shot on Jump, Google’s 360 camera rig.

The Jump rig contains 16 cameras that record every angle simultaneously, before the imagery is stitched together. And I’m watching it back through a headset made out of folded cardboard, with the screen provided by a standard smartphone slotted into the front. Google calls it, quite simply, Cardboard. You might have seen one already, and had a go. Even if not, you’ve probably seen the 360 videos spreading across YouTube and Facebook, where you can change the angle of what you’re looking at by tilting your smartphone. There are thousands of them out there already, covering everything from sports events to video games, rollercoaster rides to pop videos.

For example, you can watch a 360 film recorded by BBC Future inside a bitcoin mine below, or on our Facebook page.

“If VR is about experience, and memories, and dreams… then the idea of medium kind of doesn’t make any sense,” says Jessica Brillhart, principal filmmaker of VR at Google, who has an infectious passion for VR filmmaking. She’s shown me this clip because she says it illustrates what she thinks VR does well – capturing moments and emotions in raw, unedited ways.

It’s clear Google’s strategy for 360 video is to follow what has worked so well for it on YouTube already: putting the creation of short, attention-grabbing content into user’s hands.

“If I could film Machu Pichu, or a group of [Google] engineers, which would I choose? Most people would choose Machu Pichu, but the thing that resonates more, is the possibility of creating a memory.”

The promise of VR, in Brillhart’s eyes, is not only about transporting us elsewhere – it’s as much about connecting us to what matters to us most.

***

I’m stood in a New York subway car, the L train heading towards Brooklyn from Manhattan. It’s just ground to a halt, the lights flicker off, replaced by the dim glow of emergency lighting. I walk the length of the car, peering at the grimy details on its floors and walls. I pause by a guy sat by the doors, and as I absentmindedly stare at him I realise I can hear his thoughts, his inner monologue. He’s complaining about the smell on the train, about being trapped here. As I turn away his voice fades to nothing – as I turn back I can hear him again.

Scatter

ScatterBored with his moaning I walk forward a few more steps, and approach a woman that’s leaning against a pole. Like the man earlier she’s ghostlike, formed from what seems to be a shimmering mixture of video and iridescent floating pixels. Again, as I stare at her, I tap into her thoughts. I can hear her worrying about the cost of living in NYC, about how she can’t be stuck on this train for much longer, how she’ll be late.

I pull the virtual reality headset from my face. For a fraction of a second I’m not sure where I am, before my eyes adjust to the light and I remember that I’m in a small, slightly scruffy basement studio space, filled with computers, camera rigs, and VR headsets. I’m in Brooklyn’s ultra-hip Williamsburg neighbourhood, just across the street from an actual L train stop, and I’ve just experienced an extract from Blackout, a fully interactive VR story.

Scatter

ScatterWith VR so associated with allowing you to do the unusual, to escape from everyday experiences and live your dreams and fantasies, it might seem odd to put so much time into recreating something so mundane as riding a subway train. “Blackout is sort of a homage and a provocation towards acknowledging the people that are in your real space, and using the medium of virtual reality to turn a lens back into the actual reality,” explains James George, one of the project’s co-creators. “We are literally right next to the subway train here, why have we recreated something that’s right here? In virtual reality we immerse ourselves in a space where you can actually ignore the physical world, [but] for us, this is taking us right back to the city that we live in, but we’re creating a magical realism layer over that city.”

The aim of Blackout is to challenge assumptions New Yorkers might have about the people around them, by allowing them to tap directly into their thoughts. “You’re given the ability to pick into people’s minds and their motives,” says co-creator Alex Porter. “Through that process you start to realise the ways in which you were wrong about all the people around you, and start to find these kind of exciting stories that they have to tell.”

It’s clear from the second you start Blackout that it’s a different, far more immersive VR experience than Google’s 360 video, or even Giant. It’s running on HTC and Steam’s Vive hardware, which combines a very advanced, high-resolution headset with wall-mounted trackers that know not just which direction your head is facing, but exactly where it is in the room. This means that rather than sitting on a chair and just moving your head, you can move around freely in the – admittedly small – virtual space. HTC and Steam call this a ‘room scale experience’, and it’s quite unique. I’ve tried a number of Vive demos as well as Blackout, including some where you hold special controllers in each hand that allow you to interact with virtual objects. The system gives you an incredible feeling of inhabiting and interacting with a palpable space. It’s not, however, cheap. The Vive hardware costs $800, and you’ll need a powerful, high-end PC that’ll cost about the same again to get it running.

Scatter

ScatterCreating VR content isn’t all that George and Porter do, however. Under the company name of Simile they also create tools for other VR creators, the best known of which is DepthKit, a system that combines a digital camera with a Microsoft Kinect, allowing human actors to be filmed in 3D. It’s how the human characters in both Blackout and Giant were recorded. George and Porter’s aim is to make this technology cheap and widely available, believing – like Brillhart at Google – that VR will really shine when the ability to create content is put into the hands of the general public.

“We live in a YouTube society where consumption and creation are very parallel,” says George. “Things like Periscope, Instagram – people are creating as well as consuming.” VR is, however, still seen by most as something you only consume. “The message people are getting is ‘this is made by important, smart people who are very technically proficient and going to show you branded content and celebrities’. It’s very exclusive to this elite group of people who are able to make content right now. We are making a case for the fact that these means of production are actually much more accessible.”

“Giving those people the tools, for me personally is way more exciting than like Michael Bay making whatever,” adds Porter.

“That said, if Michael Bay wants to use it then feel free,” says George, not wanting to alienate a potential customer.

***

I’m sat in the cockpit of a futuristic tank. Controls surround me, panels of flashing lights. I want to reach out and touch them, but before I can try the tank starts to move – heading down a long narrow tunnel that opens out into a huge, cavernous space. Rows of other tanks flank the sides next to me, while Tron-like robots float past. Next I’m being scooped up on a lift, and I gaze up at the ceiling as massive hangar doors above me slide apart.

And then I’m outside, on the surface, staring up through the tank’s cockpit at huge, spindle-like neon towers that reach into the sky. But before I can finish admiring the view an urgent computer voice grabs my attention. Incoming. A glance down at the radar on my dashboard, two red dots heading towards me. I look left and right anxiously out of the cockpit. There they are: two enemy tanks heading in for the kill. I prepare myself for combat…

Rebellion

RebellionI pull the virtual reality headset from my face. For a fraction of a second I’m not sure where I am, before my eyes adjust to the light and I remember that I’m in the large, open plan offices of Rebellion, the British video game company based in a leafy neighbourhood of Oxford. I’ve just played a demo level of Battlezone, the VR update of the 1980s Atari arcade classic.

Just as immersive and interactive as the Vive demos I’ve tried, one of the things that makes Battlezoneso interesting is that it’s running on Sony’s PlayStation VR hardware. Due for release in late 2016, the headset needs a PlayStation 4 to work, but costs less than half the price of a Vive. It also looks and feels far more like a consumer product than any of the other headsets currently on the market – it’s easy to put on and take off, and is light and comfortable to wear.

“I think they’re all great machines, but I think Sony’s VR will be the mass market,” Jason Kingsley, Rebellion’s CEO, tells me. “Simply because of who Sony are. Simply because of the price point. The tech is very good and easily sufficient to do good VR. The others kind of get the feeling of being a bit more hobbyist.”

It’s easy to be convinced of this, based on the thrill of playing Battlezone for a few minutes, and experiencing how immersive it is. But I can’t help think of other video game gadgets and add-ons that came and went. The PlayStation Eye. Move. The Xbox Kinect. Even the Nintendo Wii. All seemed to come along and grab people’s attention for a while, before ending up gathering dust on the shelf as gamers returned to more traditional ways of playing games when the novelty wore off. Is he not worried the same could happen with VR?

“It’s not a fear of mine, but it's a possibility. It’s a lucid possibility for any kind of new thing. I think it will be successful,” he says.

Rebellion

Rebellion“If you try it, you will want to buy it,” adds Steve Bristow, Battlezone’s lead designer. “Whether it lasts and how long it lasts for depend on how well we do our job and fulfil those promises, or surprise players with what you can do. I’ve got complete confidence in the game-making community to continue finding new ways to surprise you with it. I think VR is coming at a really good time for conventional flat games, because I think it’s becoming increasingly difficult to produce those kind of emotional experiences, fresh, powerful emotional experiences, in flat games.”

For Kingsley, VR is more than just a new gaming gimmick, it’s a fundamental shift in the gaming experience. “Playing a really great computer game, watching a great movie, you’re really in there, but you’re an observer,” he tells me. “In a really good computer game, you are a participant and an observer, so we’re kind of one step closer. We’re a little closer to that screen. We’re kind of nose against the screen. I think with VR you get the feeling you’ve stepped over and you’re in it.”

***

I’m sitting at home, on my sofa, a Cardboard headset lying on the seat next to me. My head and eyes hurt from overdosing slightly on 360 video and VR apps. I’m trying to decide how I feel about the new technology, about everything I’ve been told by the people I’ve met. I’ve been excited by the concept for years, ever since I came across it in science fiction in the 80s. I’ve even written science fiction about it. But now, with the weight of age and experience of watching technologies come and go, it’s hard not to be worried that it might just be a fad.

Andrew Schoen is a VC with New Enterprise Associates, a large, global venture capital firm that has been investing heavily in VR projects, from games companies to 360 recording hardware. As such, he’s putting his – or at least his company’s – money where his mouth is.

Getty Images

Getty Images“If you are investing in virtual reality, what you need to embrace is the cockroach,” he tells me over the phone from California, talking about sitting out the initial hype cycle. “You need to survive. You need to watch as there is turbulence in the ecosystem. You need to know that will happen around you, be aware of it, and survive that hype cycle. There will be a very exciting period on the other end of it, but expectations are just so high today that there will be – I would say – a bit of a gap to bridge in terms of delivering on the promise of some of those expectations.

“In a way, where we are today looks a little bit more like the early development of the film industry, where the novelty of watching a train heading straight towards the audience was enough to make an audience say, ‘Oh wow!’ and jump out of their seats.” For the near future, he says, the novelty is enough.

Perhaps he’s right. Perhaps this year’s hype around VR is just the beginning, and when it inevitably blows over we’ll be left with something more stable and normalised – a new way of sharing experiences, a new way of capturing our memories, or a new way of playing games. Or maybe it’ll just disappear into nothing, a forgotten technological fad to be replaced by the next new, shiny thing. Either way, I can’t help wondering about the people I’ve met who have invested so much of their lives into it, and how many of them will be able to become like Schoen’s cockroaches and weather the storm.

Join 600,000+ Future fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us onTwitter,Google+,LinkedInandInstagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital, Travel and Autos, delivered to your inbox every Friday.