The builder who changed how the world keeps time

Igor Goncharenko/Alamy

Igor Goncharenko/AlamyBritain introduced daylight saving time 100 years ago – and was quickly followed by countries worldwide. Love it or hate it, there’s a stubborn British campaigner you can thank.

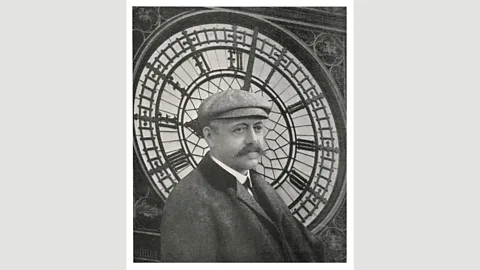

He lived in the south-east London suburb of Chislehurst. He was a builder. He was of average wealth. His name was William Willett and without him Britain – and a quarter of the world, including the US – might never have adopted daylight saving time (DST).

A lover of open spaces, Willett was horseback riding one summer morning in 1905 when, ruefully, he observed how many curtains remained drawn against the sunlight. A solution occurred to him: why not move the clocks forward before each summer began?

The National Trust Photolibrary/Alamy

The National Trust Photolibrary/AlamyWillett wasn’t the first to conceive of such a measure. Ancient civilisations shortened and lengthened days depending on the season – a Roman hour, for instance, could last 44 minutes during winter, but 75 in summer. In 1895, New Zealand entomologist George Hunter had proposed a two-hour shift but saw his idea derided. Six years later in 1901, King Edward VII put the clocks back 30 minutes at Sandringham so he could hunt for longer.

But it took Willett for DST to – eventually – come to pass. By 1907, he had self-published a pamphlet, Waste of Daylight, which advocated that time be advanced by four 20-minute increments during April, then similarly reversed in September. Along with more recreational opportunities, Willett said, this would lower lighting costs.

His cheerleaders included prominent politicians like David Lloyd George and a young Winston Churchill, then president of the Board of Trade. Discussing the newly-proposed Daylight Saving Bill, Sherlock Holmes author Arthur Conan Doyle also came out in favour, though he disliked Willett’s fastidious adjustments. “A single alteration of an hour would be a round number, and cause less confusion,” Conan Doyle said before the bill’s select committee.

But crucially, the opponents included Prime Minister Herbert Asquith. The bill was narrowly defeated in 1909 as were subsequent proposals. Tinkering with time was, it seemed, too radical a move – even for the reformist Liberal government. Undeterred, Willett continued to furiously campaign in Britain, Europe and America until dying from influenza in 1915.

Chronicle/Alamy

Chronicle/AlamyJust a year later, a revised version of his scheme was finally accepted due to the most extenuating circumstance of them all: war.

Two years into the World War One, Britain was running desperately short on coal – the chief source of power for its industry and households. “Not only was there increased demand to fuel the navy, railways and armaments industry, but Britain had to supply allies whose coalfields were German-occupied, plus thousands of miners had volunteered for service,” says David Stevenson, history professor at the London School of Economics.

Willett’s ideas promised relief: longer evenings and less demand for coal-powered lighting. After Germany ratified a DST bill on 30 April 1916, Britain promptly followed suit with its own Summer Time Act, passed on 17 May.

Such copycat behaviour was commonplace, Stephenson says. “Britain had long been borrowing from Germany – many British politicians and intellectuals were fascinated by the country as an example of superior national efficiency,” he says.

According to the new law, civil time would be advanced one hour ahead of Greenwich Mean Time during the newly-defined British Summer Time. Several other European nations soon followed suit, along with the US – coining its famous mnemonic of ‘spring forward, fall back’ – as well as Uruguay, New Zealand, Chile and Cuba.

Double-time it

Britain went on to witness occasional deviations. During World War Two, it operated two hours ahead of GMT in so-called Double Summer Time, once more to cut industrial costs. Trialled between 1968 and 1971 was British Standard Time, which advanced clocks by an hour year-round. Characterised by children wearing fluorescent armbands on inky winter mornings, it proved deeply unpopular.

Ever since, recurrent parliamentary bills have challenged DST. Not just in Britain, either: daylight saving measures are constantly being introduced, amended, disputed or ditched somewhere around the world.

Gary Moseley/Alamy

Gary Moseley/AlamyWhy is it such a contentious subject? Chiefly because the pros never convincingly overwhelm the cons. For every compelling DST argument, there’s always a persuasive counter. Broadly speaking, DST is thought to aid retail, sports and tourism – but hurt those in agriculture and mail delivery.

No one is better versed in the debates than David Prerau, author of the book Seize The Daylight. “DST is generally thought to reduce energy usage, traffic accidents and outdoor crime and to bring a better quality of life,” he says. “But the negatives include dark mornings – a problem especially for schoolchildren and farmers – and a jetlag effect on sleep patterns.” A recent Finnish medical study even tied DST to strokes, blaming the disruption to the body’s circadian rhythms.

Often, clock changes are a political tool. While celebrating 70 years of liberty last August, North Korea moved its clocks back 30 minutes, returning to a time zone it utilised prior to Japan’s occupation – which the state news agency said was done to "root out the legacy of the Japanese colonial period.”

Of the world’s population of 7.4 billion, around one-quarter use DST. Prerau is in no doubt about who deserves the credit. “The passage of DST laws came directly from William Willett's efforts,” he says.

Inspecting Willett’s plain grave outside Chislehurst’s sleepy St Nicholas Church, it seems scarcely believable that he had such long-term global influence.

Locally, Willett’s legacy is acknowledged with a pub called The Daylight Inn, a plaque on his old home, roads bearing his name and letters, documents and photographs displayed at the Chislehurst Society’s new community hall. But does he merit wider recognition?

“Definitely,” says Joanna Friel of the Chislehurst Society. “Willett campaigned so passionately, and simply refused to give up. He was a remarkable, and ultimately very important, figure.”

Imagestate Media Partners Limited - Impact Photos/Alamy

Imagestate Media Partners Limited - Impact Photos/AlamyOne of Willett’s great-great-grandsons is Chris Martin, lead singer in the British rock band Coldplay. The opening lyrics of their single Clocks – “the lights go out and I can't be saved” – contain a possible reference to DST.

This year, Coldplay are headlining Glastonbury Festival. They’ll take the stage at about 22.15 on Sunday 26 June, almost exactly as dusk falls, thanks to British Summer Time.

Whether you’re relishing the light-filled evening outdoors or in, spare a thought for William Willett: the man who changed time.

Follow BBC Future on Facebook, Twitter, Google+ and LinkedIn. This story is a part of BBC Britain – a series focused on exploring this extraordinary island, one story at a time. Readers outside of the UK can see every BBC Britain story by heading to the Britain homepage; you also can see our latest stories by following us on Facebook and Twitter.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital, Travel and Autos, delivered to your inbox every Friday.