The beauty of big engineering as you’ve never seen it before

Google Earth

Google EarthLooking down from above, there's something beautiful about the human mark on Earth.

You don’t need to fly the globe to get snaps of some of the world’s most stunning views. A project called Google Earthview has now transformed Google Earth images into beautiful, downloadable still photography. The colours are enhanced, but everything you see is a real satellite image.

Many of the images capture ambitious engineering projects from an aerial view as you’ve never seen them before. We decided to look at the human footprint on Earth through the eyes of Earthview and discovered that when it comes to engineering, big can be beautiful.

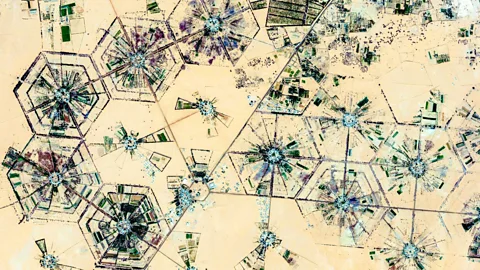

Irrigation system, Al-Jawf, Libya

Al-Jawf, a town in Libya, is almost completely dependent on irrigated water. In the image below, the hexagonal shapes etched into the surface of the Sahara Desert represent agricultural oases up to 1km in diameter.

Google Earth

Google EarthThe area receives almost no rainfall, so the water supply for the area is pumped from fossil water stores deep underground. Fossil water is normally a non-renewable resource, unlike surface reservoirs that are replenished by rainwater, which means it could eventually run out. The practice of extracting stored water is common in deserts like the Sahara and Kalahari.

However, in 2013 satellite images revealed that some of the fossil stores in the Sahara are resupplied annually by an average of 1.4km-cubed of water. This equates to about 40% of the annual withdrawals, so while it doesn’t totally account for the extracted water it could allow for sustainable management of the main water resource in the otherwise arid Sahara.

Solnova Solar Power Station, Seville, Spain

Solnova Solar Power Station in the image below is just one part of Europe’s largest solar farm, the Solucar Complex. The plant is made up of five units (three are pictured), each covering approximately 300,000 sq m. A “concentrating power plant”, it is made up of rows of curved mirrors that reflect sunlight onto pipelines containing oil. The oil can reach temperatures of 400C, which then heats water vapour in the generators pictured towards the centre of each unit.

Google Earth

Google EarthBy completion, it will be the world’s largest concentrating solar power plant with a capacity of 250MW. The whole Solucar Complex project, seen in more detail below, aims to serve more than 150,000 Spanish homes and to reduce annual carbon dioxide emissions by 185,000 tonnes.

Google Earth

Google EarthMaatschap Europoort Terminal, Rotterdam, the Netherlands

The Maatschap Europoort Terminal (MET) at the port of Rotterdam serves as a store of crude oil. Currently the terminal can store 1.6 million metres cubed of oil across its 21 tanks. The oil is then transferred all over Europe, although it isn’t uncommon for sites like this to hold onto their oil for long periods of time.

Google Earth

Google EarthWe recently covered the United States’ massive “Strategic Petroleum Reserve”, made up of 60 subterranean caverns storing 700 million barrels of oil for use in the event of shortages. Many governments around the world have similar facilities to avoid recurrences of the 1973 energy crisis when Arab oil exporters withheld oil from the US in response to their support of Israel in the Yom Kippur War.

The port of Rotterdam, with an annual throughput of 450 million tonnes, is the largest port in Europe. “Liquid bulk” – which includes crude oil – makes up about 50% of everything handled through the port.

IJsseloog, the Ketelmeer, the Netherlands

IJsseloog is a man-made reservoir 1km in diameter for silt collected from the Ketelmeer, a lake that joins the river IJssel to the IJsselmeer. By dredging silt from the lake it can be kept as deep as possible. In doing so, the Ketelmeer and the river IJssel, which drains into it, can remain open to boat traffic.

Google Earth

Google EarthMuch of the network of waterways in this area of the Netherlands was created when polders of land were reclaimed from the Zuiderzee. This reclaimed land forms islands and is only accessible through connecting bridges. The polders also serve to protect the country from rising sea levels: around one third of the country lies below sea level, and without manmade dikes and dunes, 65% would be below water at high tide.

Copper and gold mine, Akjoujt, Mauritania

This image shows a copper and gold mine in Akjoujt, Mauritania. Blue colouring on the sand is caused by oxidised deposits of copper around the mine-head. When copper comes into contact with the atmosphere, the oxygen and water react with its surface to produce copper carbonate, giving it a green/blue hue.

Google Earth

Google EarthMinerals like copper and gold are an important resource to the country. While other mineral resources are in decline, salt being a notable example, copper continues to be mined. In 2006, the mine’s owners, First Quantum Minerals, produced their first haul of gold – amounting to 322kg. The mine was expected to produce about 3,300kg of gold per year.

The Pearl-Qatar, Doha, Qatar

The Pearl-Qatar is an artificial island still under construction in Doha’s West Bay Lagoon. At completion, the island will be filled with luxury hotels, residences, shops and restaurants to draw in wealthy expats from all over the world.

Google Earth

Google EarthLike Dutch polders, these luxury islands are built from land reclaimed from the water by dredging it up from the shallow seabed. A similar project in Dubai, the United Arab Emirates, called The World is not faring well after construction stalled in 2008. The small artificial islands that make up the project will erode without continued maintenance. Environmentalists have warned that eventually the project would sink completely.

Residents began moving to move into The Pearl-Qatar in 2012, but construction on the whole island isn’t due to finish until 2018.

Venice, Italy

The city of Venice is in itself a feat of engineering. The City of Water survives in the face of the rising Venetian lagoon thanks to the innovation of scientists from all over the world.

Large-scale tectonic activity is pushing the ground underneath the city towards the Apennine Mountains. As a result the city is sinking. The annual rate of sinking has been diminishing through ground water pumping, the construction of barriers and inflatable gates but this isn’t a long-term solution.

Google Earth

Google Earth"No matter what they did by stopping the groundwater pumping, they're still going to have a natural subsidence on the order of about up to 2mm a year,” Yehuda Bock of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, California, told BBC News in 2012.

"The figure is a little larger than many were expecting, so I think they may end up using these new barriers more often than they thought.”