The geniuses who invented prosthetic limbs

Moments of genius can strike at unexpected times. Here we look at some of the fearless inventors who pushed forward prosthetic technology.

Easton LaChappelle's brainwave for building a new prosthetic arm came after he was bored in class.

He stumbled across a cheaper alternative to the expensive prosthetic limbs currently available, as the video below shows.

The history of prosthetic limbs is littered with such masterstrokes.

The world’s earliest functional prosthetic body parts are thought to be two examples of artificial toes from Ancient Egypt. These toes predate the previously earliest known prosthesis – the Roman Capula Leg – by several hundred years. What makes them unique is their functionality. Early prostheses were mostly decorative, but these Egyptian toes are an early example of a true prosthetic device.

“The big toe is thought to carry some 40% of the bodyweight and is responsible for forward propulsion,” said Dr Jacky Finch, then at the University of Manchester. Modern prosthetic toes would be produced only after intensive study of an individuals 's gait using cameras and other monitoring equipment.

Dr Jacky Finch

Dr Jacky FinchDr Finch selected two volunteers to test replicas of the toes and to their surprise they were very comfortable: “My findings strongly suggest that both of these designs were capable of functioning as replacements for the lost toe and so could indeed be classed as prosthetic devices. If that is the case then it would appear that the first glimmers of this branch of medicine should be firmly laid at the feet of the ancient Egyptians.”

Dark Age design

In general, artificial limbs moved forward little up to this point. However, this iron prosthetic, belonging to Gotz von Berlichingen (1480-1562), a German knight who served with the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, shows how they came to incorporate hinges.

Science Museum London/Science and Society Picture Library CC BY 2.0/Wikimedia

Science Museum London/Science and Society Picture Library CC BY 2.0/WikimediaArtificial limbs like these were expensive but allowed wearers who had lost a limb to continue a fighting career. The articulated fingers could be used to grasp a shield, hold reins or even a quill. This limb was manufactured for von Berlichingen by a specialist armourer.

Centuries later, huge number of casualties in the American Civil War caused demand for artificial limbs to skyrocket. Many veterans turned to designing their own prosthetics as a response to the limiting capabilities of the limbs on offer.

James Hanger, one of the first amputees of the war, patented the ‘Hanger Limb’. Samuel Decker (pictured) also designed his own artificial arms and became a pioneer of modular limb design.

National Museum of Health and Medicine CC BY 2.0

National Museum of Health and Medicine CC BY 2.0In the design pictured, Decker has a spoon attached to his mechanical arms, recognising the need to be able to perform everyday activities with his prosthetics. Designs now needed to do more than replace the lost limb, they needed to offer the young amputees some of their former abilities back. For the first time, a generation of young men would now lead lives as amputees. Decker went on to become the official doorkeeper at the US House of Representatives.

Around 1900, the pioneers of prosthetic design had begun the idea of specialised artificial limbs. Limb design looked to more than just decorative uses and became increasingly more specialist.

Wellcome Images CC BY 2.0/Wikimedia

Wellcome Images CC BY 2.0/WikimediaWide spread fingers, index, middle and ring finger smaller than normal, and padded tips on the thumb and little finger, the above prosthetic had one specific purpose. This is an example of an artificial arm for a pianist who would go on to perform at the Royal Albert Hall, London, in 1906. The spread fingers allowed her to span one entire octave.

Despite her moment of fame, the name of the female pianist is now unknown. The Science Museum, where this limb is now kept, has done their best to discover her identity. If you know who it could be, get in touch.

Modern methods

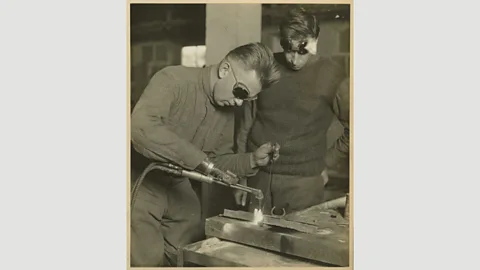

For the first time, artificial limbs were being mass-produced in response to the enormous number of casualties in World War One. In the US, the Walter Reed Army Hospital produced a large number of artificial limbs for the returning veterans. This example is of a welding attachment and other tools integrated into the limbs for amputees to return to work after the war.

National Museum of Health and Medicine CC BY 2.0/Flickr

National Museum of Health and Medicine CC BY 2.0/FlickrIt wasn’t all work, however. Also in the collection of the National Museum of Health and Medicine, USA, is an attachment for playing baseball. The Walter Reed Army Hospital is still a centre for artificial limb production in the US, 100 years later.

The technology continued to develop after WW1. DW Dorrance invented the split hook artificial hand shortly before World War I. It became popular with labourers after the war who were able to return to work using the attachment because of its ability to grip and manipulate objects. It’s one of the few designs that have remained relatively unchanged over the past century. Dorrance demonstrated its multi-functionality in the 1930s by driving a car using the arm.

Imperial War Museum CC BY 2.0/Wikimedia

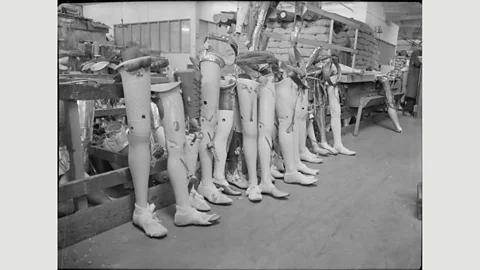

Imperial War Museum CC BY 2.0/WikimediaIn the UK, Queen Mary’s Hospital, Roehampton, became a centre for manufacturing artificial limbs in the World War Two. It opened in 1939. In its first year, 10,987 war pensioners attended the centre, with an additional 16,251 limbs being sent by post. At the outbreak of war, the factory was expanded because of the realisation that 40,000 UK servicemen had lost limbs in WW1.

However in WW2 there was around half the number of amputees. As Leon Gillis, QMH Consultant Surgeon from 1943-1967, observed, advances in surgical techniques, treatment of infections and the availability of blood transfusion after WW1 all reduced the need for amputation