Exoskeletons: My friend with a robot skeleton

When Marcus Woo’s friend Daniel suffered sudden paralysis, the outlook seemed bleak. But then an intriguing offer to be a test pilot for a pair of bionic legs came along...

Daniel Fukuchi and I are walking down a basement corridor with white cinderblock walls and glaring fluorescent lights overhead. He's a little slower, but to be fair, he's partially paralysed from the waist down.

Usually, he can hobble along with crutches for a few feet before losing steam. But today, he's moving at a decent clip, putting one foot in front of the other, straight down the long hallway. The source of his newfound power? An exoskeleton.

The device straps to his waist and thighs, and is powered by two motors at the hips that drive his legs forward. The motion is smooth, and the machine hums with every step. Fzzp. Fzzp.

Every week for the past year, Daniel has been coming to this nondescript basement lab at the University of California, Berkeley, where he's helping to test an exoskeleton designed to put paraplegics back on their feet. "It seemed like it could be something that could potentially help me," he says. "But at the bare minimum, it'd be just kind of fun to play in a robot."

Of course, it's not all play at the Berkeley Robotics and Human Engineering Lab, which is led by robotics expert Homayoon Kazerooni. His first foray into exoskeletons was in developing machines to help soldiers carry heavy loads in the battlefield, resulting in the HULC exoskeleton that's now been licensed to Lockheed Martin. But in the last few years, he has turned his efforts to designing exoskeletons that help people with disabilities. In 2011, in perhaps his group's most high-profile achievement, they built an exoskeleton that allowed a paraplegic Berkeley student named Austin Whitney to walk at his graduation.

"The overarching goal here is to create independence for people with mobility disorders and allow them to walk," says Kazerooni (his students just call him "Kaz."). For him, the exoskeletons are about more than ambulation. It's about giving people independence. "I want to use everything I have in terms of knowledge and resources to get to that goal," he says. "I'm not going to quit until it's done for people with mobility disorders – it's a part of my being; it's a part of my everyday struggle."

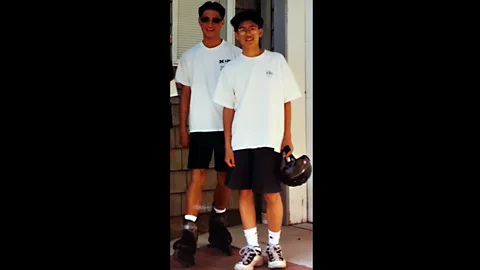

Helping Kazerooni reach his goal are people like Daniel. We have been friends since the first grade. Our childhood was filled with bike rides around our suburban neighbourhood and basketball games at the schoolyard. Both of us were always on the small and scrawny side, so when we first picked up a basketball in the second grade, we resorted to unorthodox shooting techniques. I had to heave the ball from between my legs while he would launch it as if it were a javelin.

Many years later, just a few weeks before we would head off to college in the summer of 1999, he and another childhood friend rang my doorbell, sporting roller blades. I joined them with my bike. It turned out to be the last such neighbourhood jaunt that Daniel and I would ever take.

By the end of August, I had already started college while Daniel was on vacation in Hawaii with a friend. He was surfing one morning at Waikiki Beach, but within 45 minutes, he felt a throbbing pain in his lower back.

Assuming he was just out of shape, he ignored it. After 30 minutes, though, he decided to return to shore, where he noticed increasing weakness in his legs. Soaking in the hotel bathtub didn't help, and after a couple more hours of getting progressively worse – and after some cajoling from his dad over the phone – he went to the hospital. "By then," he says, "I was completely paralysed from the waist down."

He was soon diagnosed with transverse myelitis, a rare neurological disorder caused by inflammation in the spinal cord. Doctors suspect that in Daniel's case, his own immune system attacked his nervous system. According to the US National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Strokes, there are 1,400 new cases every year and 33,000 Americans suffer from some sort of disability caused by the disorder. Some people fully recover while others remain disabled for the rest of their lives.

Daniel slowly regained some feeling and motion, but any improvements plateaued after about seven years, and he still needs a wheelchair and crutches to get around. Then, a little over a year ago, he found out that Kazerooni and his lab were looking for test pilots, and he jumped at the chance. "I mean, who doesn't want to have 'test pilot' as one of your potential job descriptions?" he says.

Kazerooni's basement lab is tucked away behind a heavy door at the end of a hallway. Taped onto the door is a printed black-and-white portrait of Kazerooni. It says "KazLab" in block letters and the text at the bottom reads, "Sciencing as fast as we can!"

At first glance, the lab doesn't look like anything more than a tinkerer's garage. Books, papers, duct tape, screws, nuts and bolts, and other random items are scattered on metal tables, desks, and bookshelves. Then you might notice the small sign, high on the wall, that reads, "KAZLAB: We make suits like they have in the FUTURE." From the ceiling hangs one of these suits, a version similar to Daniel's but with full legs and motorised knees. Around the corner is a separate room, where about half a dozen more suits hang – HULC prototypes and earlier exoskeleton designs – as if it were a cyborg's closet. Lying on a desk and seemingly forgotten is what appears to be a mechanical arm, on which the actor Alan Alda has signed and written, "Hope to wear this one day!"

The earlier versions of Kazerooni's exoskeletons were big, heavy machines that supported a person's back and the entire legs, motorising every movement of each step. Most exoskeletons now on the market follow this model – for example, the machines being built by Ekso Bionics (formerly Berkeley Bionics), a company that Kazerooni founded in 2005. The company's exoskeletons are designed for supervised use in hospitals or other medical institutions as a means of therapy for paraplegics and stroke patients.

But Kazerooni, who's no longer affiliated with the company, has since shifted strategy, aiming to create simpler exoskeletons that people can use by themselves at home. Whereas conventional exoskeletons cost hundreds of thousands of dollars, he says he wants to cut the price down to only $10,000 to $20,000 – still not cheap, but something that someone could conceivably buy.

To do so, his team is moving away from a one-size-fits-all approach and towards minimalist exoskeletons that are tailored for the individual user. Not everyone with a mobility disorder is completely paralysed, and not everyone is equally fit and strong. "It's a continuum from Usain Bolt to [the late] Christopher Reeve," says Michael McKinley, a graduate student in the lab.

For example, because Daniel has some control of his knees, he doesn't need a fully articulated suit that moves his entire leg. Foregoing extended legs means his machine can be 10lbs lighter, resembling a motorised hip more than an exoskeleton.

You can add and subtract components depending on the user's mobility – a modular approach that makes mass production easier and cheaper, McKinley says. "We can mix and match the components to really fine-tune this final machine to what you need." Eventually, he says, getting a tailored exoskeleton could be akin to getting a prescription for eyeglasses.

That day doesn’t seem quite so far away as Daniel continues one of his test walks in the corridor just outside the lab. To take a step, he pushes a button on a hand-held controller. A graduate student named Brad Perry is also with us, timing the walk and making sure the machine is working properly while Daniel relays any problems he's having with the exoskeleton. Today, the button seems to have a delayed response, causing a slight hitch in the step. The electronics box Velcroed to his back also keeps falling off, and so Perry is constantly reattaching it with duct tape.

Faster, better

To be sure, there are still improvements to make, but even in its current form, Daniel’s exoskeleton allows him to walk farther and faster than if he were just on his crutches. "When I take it off, I notice just how much longer it takes me to move – how much shorter my steps are," he says.

The exoskeleton isn't designed for terrain other than paved, even ground. But that still would be a major improvement for people with mobility disorders, Kazerooni says. He envisions that in the future, an exoskeleton will allow a person normally confined to a wheelchair to walk to the bus stop and take the bus to work, and when in the office, walk to the conference room, the water cooler, or the bathroom. These are simple movements but significant ones that could change a person's quality of life.

"I don't know if we're ever going to get the point where this replaces someone's wheelchair," McKinley says. "But that may not be the objective." The goal is to provide another tool to give someone independence. A wheelchair, he points out, is really efficient. But long-term confinement to a wheelchair carries a host of health risks, such as back problems, pressure ulcers, and poorer overall health. An exoskeleton won't just help people reach the top shelf, it could also drastically improve their health just by getting them on their feet.

Indeed, Daniel says that his main use of an exoskeleton would be for rehabilitation work to maintain his strength and balance. It's also something he can use to help him run errands when a wheelchair is too cumbersome or crutches are too slow.

"One of the things I really like about exoskeletons is the non-invasive approach," Daniel says. He's a candidate for various surgeries or new drugs that may help him regain some mobility. But an exoskeleton gives him that with less risk.

Smooth interaction

In addition to the practicalities of getting around, the exoskeleton makes human interactions more personal. "When you're in a wheelchair, you're in a bubble," Daniel says. Because people are afraid to burst that bubble, they're reluctant to come close or to interact as they would if you were able-bodied.

So much of life is meant to be experienced standing up, he says. "That's part of the appeal of exoskeletons – a return to a more normal fit within society." Simply putting you at eye-level can change how people see you. "It improves the quality of life more through interpersonal communication," he explains. People don't have to bend down to shake your hand, for example. "If you stand up and shake their hand, it's a different meaning," he adds. "It feels different."

As I watch Daniel walk with the exoskeleton, what strikes me most is that none of this seems remarkable at all. Even though the simplicity is by design, the device still almost looks ordinary – not something from a science-fiction movie. Maybe that's the surest sign that when it comes to exoskeleton technology, the future is now. We're only amazed by technology that seems outrageous, by gizmos that enable us to do things beyond our dreams. But a motorised machine that helps people walk? Sure, why not?

Watch Daniel walking and playing football (Berkeley Robotics)

And we really may see exoskeletons sooner rather than later: Kazerooni tells me that the new exoskeletons will be available in as little as one year. They likely won't be perfect, but the technology will continue to improve. The suit still has to be approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, a nontrivial hurdle if it's intended for unsupervised usage in the US. Whether or not insurance companies will help pay for these machines is yet another obstacle to accessibility. But that's no deterrent for Kazerooni. "The problems are there to be solved," he says. "I shouldn't be scared."

The normalcy – and even the nonchalance – with which Daniel embraces the exoskeleton may just be a part of his personality. Even when faced with a sudden, life-changing event, he's taken things in stride, so to speak. On the day he was paralysed, he was so calm that the emergency room nurse who greeted him didn't realise he couldn't walk, and instructed him to hop on the gurney.

"You play the cards you're dealt," Daniel says. "You can't brood too much on the cards you don't have in your hand."

He does have at least one regret about being disabled, however. Right before he became paralysed, he says he finally figured out how to consistently shoot a basketball, allowing him to beat me in a game that summer. He no longer plays, but he hasn't completely given up. After all, exoskeleton technology is constantly improving. "Who knows," he says, "maybe one day I'll be able to use it to dunk."