What science fiction can teach big business

Why are household brands that sell us kitchen appliances or snack food now commissioning science fiction authors and artists? Chris Baraniuk reports.

Tasers. Mobile phones. The world wide web. All these technologies can be found in science fiction stories, decades before they became realistic – and that’s why the medium has found an unexpected new fan.

While most sci-fi is enjoyed by movie audiences or readers, now big business is taking an interest too. Large companies including home improvement store Lowe's and confectioner Hershey are commissioning writers and artists to take flights of fancy.

One of the people responsible for this interest is Ari Popper, co-founder of the company SciFutures. Several years ago, Popper was attending an amateur science fiction writing course he had signed up to as a hobby. At the time, Popper had a day job in consulting, and he began to wonder whether there were better ways to harness that creative link between fiction and fact.

“I had an epiphany and it was, ‘this is a business!’ Well, this is potentially a business,” he says with a laugh. “You never know till you do it.”

'Hydration Hardware'

Today, SciFutures produces fictional narratives for the likes of Hershey, Del Monte foods and the US Navy, using formats such as graphic novels, artwork and roleplay. The work for most clients remains confidential, but here’s an extract from a story produced for a major beverage company, about a woman visiting a “hydration station” serving nutrient-packed water:

Diana fished her intelli-water bottle from her bag. [Jose] walked behind a waist-high counter of contoured wood and waved the bottle in front of the Hydration Hardware sensors. The vast screens along the wall poured colour in long streams of information. “You’re still not drinking enough water. And it’s flu season, you should really have the flu shot added, electrolytes, maybe some Vitamin C. How’s the knee feeling?”

“Great, actually.” On her last trip to the Oshun Hydration Station, her biometrics had told Jose about her arthritis in her knee, something she’d had since she was a child. It felt like shards of glass between her bones. Jose had suggested ionized water, Oshun’s cutting edge water additive. Her knee hadn’t hurt all week.

SciFutures has also produced work for the home improvement chain Lowe’s. What could science fiction possibly bring to a brand that sells white goods, paint and home decor? Popper explains that he started by commissioning a story and imagery about a hapless future couple who design their next DIY project using a 3D virtual reality simulator:

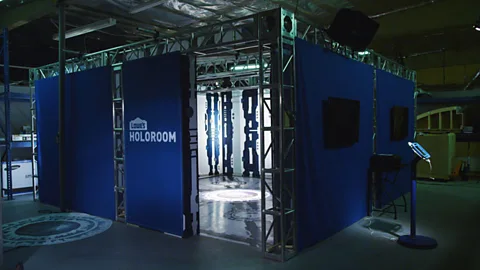

The reaction from Lowe’s was so positive that the company then decided to partner with SciFutures so that the simulator could be made for real. The first simulators, called Holorooms, will launch in two Lowe’s outlets in Toronto later this year. By peering through a tablet they hold aloft inside the room, people can stroll through their digitally rendered future home.

“You can actually walk into it using augmented reality and have a lifelike, visceral kind of 3D experience of what your home could look like,” explains Popper.

Another future-gazer turning science fiction into reality is American inventor John Underkoffler, who was the scientific advisor on Steven Spielberg’s oft-referenced 2002 film Minority Report. Underkoffler now works for a technology design firm called Oblong and is famous for coming up with the idea of a multi-screen interface which can be intuitively controlled by hand gestures.

Underkoffler’s idea wasn’t just a computer-generated fiction. He actually built it, developed a version for the US military and demoed it to the public at a TED conference in 2010. The technology has since evolved into a product called Mezzanine, which is targeted at high-paying corporate clients for use in workshops and board rooms.

Deep understanding

But is science fiction actually helpful to business – or can it sometimes be a hindrance? Not everyone is enamoured of the impact made by Minority Report. Christian Brown, a commercial artist, claims that the film has “trapped” designers in a world of “bad interfaces”.

“The reality is, there’s a huge gap between what looks good on film and what is natural to use,” he argued in an opinion piece for The Awl.

Nevertheless, for Popper, the most provocative ideas are best received through the narrative of science fiction. That’s where, he says, the audience is best able to understand how something truly novel would actually work.

“You don’t have to understand what augmented reality is, you don’t have to understand the technical specifics behind 3D printing,” he says, “because when it’s in a story form and people are using it, you totally get it, you totally understand the potential of the technology.”

Fetishised tech?

London-based design consultant and artist Tobias Revell uses the word “normalcy” to describe this quality. Normalcy is the sense that something, futuristic or not, has been depicted in a context which we understand and can relate to our own lives.

“I love the idea of talking about technology in a non-patronising, non-fantastic way by looking at it through the lens of normalcy,” he says. “You realise that technology isn’t something to be fetishised, it’s something that’s normal and part of our everyday routine.”

The commissioned work would do well to escape the rose-tinted, soft-focus views of the future that often come with corporate marketing. After all, famous science fiction, such as Blade Runner, depicts a gritty and troubled world. Contrast that with visions cooked up by more conventional corporate futurologists, and they can seem somewhat sterile and unrealistic. Revall, for instance, takes issue with the utopian design fiction of Microsoft’s “future vision” videos (see below). For him they seem, “unbelievably fake and plastic, flat-pack”.

Perhaps science fiction, then, can provide companies with a more realistic, human view of the future than their own staff could ever provide.

If so, Popper argues it could have a direct effect on the next generation of technologies we all use. “If we have a brilliant science story that everyone understands, we’ll have a much better chance of making it real,” says Popper. “It doesn’t mean we’re going to get there – but it gives us a much better chance.”