Robots: Can we trust them with our privacy?

The idea that robots will conquer humanity is a myth, says Marcus Woo, but has one of the real concerns they pose been ignored?

Joss Wright is training a robot to freak people out.

Wright, a computer scientist, is plotting an experiment with a humanoid robot called Nao. He and his colleagues plan to introduce this cute bot to people on the street and elsewhere – where it will deliberately invade their privacy. Upon meeting strangers, for example, Nao may use face-recognition software to dig up some detailed information online about them. Or, it may tap into their mobile phone's location tracking history, learn where they ate lunch yesterday, and ask what they thought of the soup.

The experiment is part of a project called Humans And Robots in Public Spaces, which is exploring how people interact with robots – and what happens when the mischievous machines know more about us than we think.

Wright is one of a number of researchers wondering whether we can trust the robots that are poised to enter our lives. If Hollywood is to be believed, the biggest danger robots pose is their superior strength and intelligence, which could destroy us all. Yet these scientists and scholars argue that the actual future of robotics looks quite different. If robots become ubiquitous, they’ll be able to constantly watch and record us. One of the greatest threats, it seems, is to our privacy. So to what extent should we be concerned?

Robots have already been working in factories for decades. Some are now in our homes, cleaning our floors, while others may soon keep a watchful eye on us as security guards or help take care of the elderly. In the last year alone, Google, which is already developing self-driving cars, bought eight robot companies.

Yet despite advances in technology and in artificial intelligence, we're still a long way from intelligent robots. What will empower them, however, is the cloud: the distributed, networked computing in which the internet lives. By connecting to the internet, robots can retrieve information and ask for help as they navigate the world, for example.

It would be the next step in a technological evolution already underway. "What we're increasingly seeing now is the existence of computers and sensing devices as part of the infrastructure that surrounds us," says Wright, based at the Oxford Internet Institute at the University of Oxford. With smartphones, the rise of wearable technologies like Google Glass, and the availability of wireless internet almost everywhere, the internet is embedding itself deeper into our environment.

"Ultimately, what a robot is or what a robot represents is an increasing presence of computers as more physical objects that we interact with," Wright says. "Those interactions are going to be very rich," he adds. "It's going to be physical and pervasive."

Perhaps that’s part of reason why some of the major web technology firms, such as Google, have been embracing robotics. Some researchers and privacy advocates are concerned that robots could act as physical extensions of these companies, giving them tremendous access into your life. For example, a housekeeping robot can gather details about your house and monitor your activities while it's tidying up. It can then sell that information about your home and hobbies to companies that can target you with ads and products.

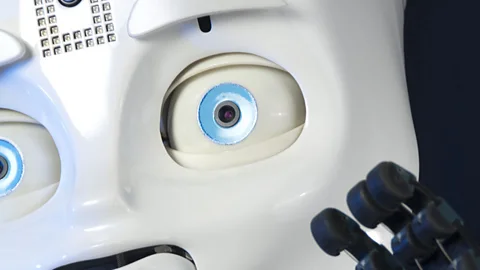

But what can really set robots apart from computers is their appearance. "If you make them look like humans, people might begin to trust them in ways that are risky," says Mireille Hildebrandt, an expert on law, privacy, and the internet at Radboud University Nijmegen in the Netherlands.

After all, people tend to treat robots as something more than another piece of technology, even if it doesn't look human-like at all. In an oft-cited 2007 study, researchers at the Georgia Institute of Technology surveyed 30 owners of Roomba, the disk-shaped robotic vacuum cleaner, and found that the majority gave their robots names and a gender, with many even considering it as a member of the family as if it were a pet.

Which is why Wright and his colleagues want to see how people react to a privacy-invading robot. The Nao doesn’t normally invade privacy (see video, below), but it can be programmed to be a robot snooper. In their experiment, Nao won’t be doing much more than what today's computers and smartphones are already doing. But those devices are inanimate objects. "What happens when it's an anthropomorphous robot?" he wonders. If it's a robot doing all these things, are people more freaked out? Less? Are they more or less willing to share information?

It’s not clear what the results will be yet, but Wright believes that there must be measures to protect our privacy from robots regardless. However, the answer isn't to stop any of our data from being shared, he says. It's about ensuring that the trade-offs in information are fair, since some of the data that robots collect can be beneficial. Robot caregivers can anticipate potential health problems by monitoring blood pressure and glucose levels, for example.

What's needed are ways to incorporate safeguards into the architecture and design of the robots themselves, Wright says, rather than patching up privacy risks after the fact. In particular, he's designing systems and protocols that only collect the data that are required for the intended task. In contrast, for example, smartphone apps and web-based email now gather all kinds of data – information that help companies learn more about you, but aren't really necessary to play Candy Crush or write an email.

But for these solutions to work, Wright says, there needs to be legal enforcement. Hildebrandt agrees. "I think it's very important that the law gets involved and we get some substantial data protection," she says. In 1995, the European Union issued a data protection directive to safeguard personal information. In 2012, the European Commission proposed to reform those rules to strengthen online privacy. "If we don't learn how to take this intentional stance," she says, "then I believe we're in deep trouble."

In today's interconnected age, there's more available information about us than ever before. And the presence of robots ups the ante: if it turns out that we are more likely to feel comfortable with them because of their appearance, then this raises serious questions about how much access they should have to our lives. After all, behind those robotic eyes, someone else may be watching.