How insects could feed the food industry of tomorrow

Would you eat meat fed on maggots? Raising pigs, chickens and fish on insect larvae could change the way we farm animals, says Nic Fleming

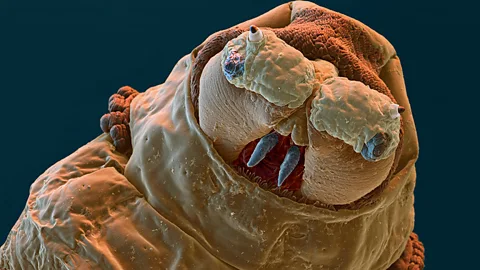

Millions of maggots squirm over blackened pieces of fruit and bloody lumps of fetid flesh. A pungent stench of festering decay hovers over giant vats of writhing, feasting larvae. It's more than enough to put most people off their lunch. Yet these juvenile flies could soon be just one step in the food chain away from your dinner plate.

Such nausea-inducing scenes are daily occurrences at a test site owned by AgriProtein, a South African company which began building what it says will be the world's largest fly farm a few weeks ago. Others in the US, France, Canada and the Netherlands are also gearing up for large-scale farming of insects to feed chicken, pigs and farmed fish.

Hundreds of people attended the Insects to Feed the World conference in Wageningen in the Netherlands earlier this month. Many of them are convinced that bugs can provide a sustainable alternative to more conventional but increasingly expensive cereals, fishmeal and soybeans.

While it may be normal for chickens scratching around a farmyard to gobble up grubs and bugs, until now no-one has taken it to an industrial scale or fed insects to animals that eat other foods in the wild. So can consumers stomach the idea of tucking into smoked salmon, chicken burgers and pork chops that come from maggot-fed animals?

The UN Food and Agriculture Organisation estimates that population growth and increased demand for meat and fish will require 70% more feed for cattle by 2050. This will put extra strain on arable land, and further pressure on fish stocks; currently, a third of the fish landed gets turned into meal to feed animals. And the cost of feeding livestock has soared. "Ingredients for traditional animal feeds are becoming increasingly expensive, especially fishmeal because of over-exploitation of the oceans," says Arnold van Huis, an entomologist at Wageningen University, and co-author of The Insect Cookbook, an English translation of which was published in March. "Cereals are used but the nutritional profile of plant proteins is not good enough. Soya is high in protein but prices have also risen sharply. We need alternatives."

It is hardly surprising that entrepreneurs are investigating new possibilities.

AgriProtein announced earlier this month that it had raised $11m to build its first two commercial-scale farms. The first, in Cape Town, will create 20 tonnes of larvae and 20 tonnes of fertiliser per day.

It uses three species – the black soldier fly, the blowfly and the common housefly. Each is adapted to feed on different types of waste, and their meals include leftover or spoiled food, manure and abattoir waste. Males and females are bred in giant cages and their eggs are extracted and mixed with its food. One kilogram of eggs turns into around 380kg of larvae in just three days. The larvae are then extracted, dried and milled, leaving behind nitrogen-rich material for compost.

AgriProtein’s Magmeal product is approved as a feed for chickens and fish in South Africa. The company is also preparing to apply for approval for an iron-rich product made from larvae fed on blood and guts for use as an additive for breeding sows; piglets aren’t born with enough iron, and in the wild animals usually get what they need from soil. In captivity, they need iron supplements. AgriProtein hope their product will be cheaper.

AgriProtein is not alone. The Vancouver-based Enterra Feed Corporation hope to triple production of black soldier fly larvae products for pet food and eventually for aquaculture feed by next summer. EnviroFlight, based in Ohio in the US, also produces feed for farmed fish made from black soldier fly larvae. Ynsect hopes to be farming mealworms and black soldier flies near Paris on a large scale by 2016. And Protix Biosystems in the Netherlands is now planning to expand its black soldier fly farming operation, selling larvae lipids for use in animal feed, and protein to pet food manufacturers.

Laws in some regions, however, are currently preventing insect-feed taking off. In the European Union, insects fall under the same rules as traditional livestock once they have been killed, dried or otherwise processed. That means their protein can be fed to pets but not to animals destined for human consumption. Even if this was to be changed, other regulations state that farmed animals cannot be fed on catering waste or manure. These regulations, drawn up in the wake of the 1990s BSE crisis, were never intended to apply to insects.

The European Commission's Directorate-General for Health and Consumers in Brussels is working towards allowing insect meal to be fed to farmed fish. But this is likely to take a year.

Different laws apply in different US states. Insect-based ingredients in feed given to animals bred for human consumption are allowed in Ohio, and manufacturers are hopeful that other states will follow their lead. The Canadian Food Inspection Agency is also considering allowing protein and fats from insect larvae to be used in aquaculture and chicken feed.

There are differing views on the speed with which the law should be revised.

"Some want to work with all kinds of risky material like manure or human faeces to open up the whole thing at once," says Kees Aarts of Protix Biosystems. "It's a bridge too far. It is also important that the industry does not over-sell itself. Insects can play an important role in providing a new source of nutrients in a world of growing demand, but they cannot solve all the big problems we're facing all at once."

Will consumers accept maggot-fed food? Many may not care – after all, the realities of industrial food production are already hidden from view for most people. And Jason Drew, who runs Agriprotein with his brother David, is convinced that a combination of the environmental benefits and the "back to nature" message will win over squeamish customers. "Out in the fields, the natural diet of chickens consists of flies, larvae, worms and ants, and wild-caught trout gets its protein from insects," he says. "That's why they jump out of the water. What we're doing is going back to an entirely natural process, and that's something people understand very quickly. Ten-to-15 years from now this will be a very big global industry."