TEDxSanaa: When TED came to Yemen

Getty Images and TEDxSanna

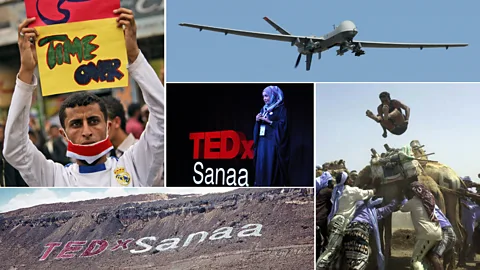

Getty Images and TEDxSannaFuturism meets champion camel jumpers, when the exclusive ideas forum arrives in the poorest country in the Middle East.

Anyone who has come across a TED talk online will be familiar with the set up: highly educated technologists and entrepreneurs, on a beautifully-lit stage, giving “the talk of their lives” in 18 minutes or less.

In that respect, this could have been any other event overseen by the global conference organizer. But this one was different: alongside the customary techno-utopian or counterintuitive visions of the future, was a champion camel-jumper, who boasted of clearing seven camels in one leap, and the head of a pigeon-racing club, who described a recent competition where some of the unfortunate competitors were “eaten by predators and others died from the weather.”

Welcome to the first TED event at Sana’a, capital of Yemen, the poorest country in the Middle East and a nation at the heart of the covert US war on Al Qaeda.

The venue was Sanaa, the capital of Yemen, the poorest country in the Middle East and a nation at the heart of the covert US war on Al Qaeda.

Yemen’s reality is at odds with much of what TED - which grew out of a laid-back Silicon Valley scene - seems to represent. For many outside the region, which once flourished thanks to the ancient spice routes, the country has become known for drone strikes against Al Qaeda suspects and for the 2011 protests - inspired by the Arab Spring uprisings in Tunisia and Egypt – that led to the overthrow of its leader.

Anyone who has been to Yemen may also know about the country’s limited internet, a dismal GDP that fell a further 10% in 2011 and the population’s endemic use of qat, a mildly narcotic leaf that is chewed daily (and is partly blamed for a host of other problems, like the country’s water shortage and truncated work day).

But it was against this backdrop that the TEDxSanaa team opened its all day event on the last day of 2012, with the theme of “inspiring hope”.

Solar fishing in Yemen

"There’s been a long history of negative perceptions of Yemen...particularly from western media,” explained Walid Alsaqaf, the lead organizer of the event. “That has really put a lot of strain on many Yemenis abroad and forced them to distance themselves from their country. So TEDxSanaa is about selecting the cream of the Yemeni crop from around the world and presenting that as an image of what Yemen could become... We are taking the first step along that thousand mile road."

Guided by this theme, many of the speeches at the five star Movenpick hotel were marked by the techno-enthusiasm that have made TED famous: Emad Alsakkaf, who describes himself as a researcher, entrepreneur, IT specialist, and farmer, spoke of his vision of aquaponic agriculture. His talk featured a fish tank with a tomato plant growing out the top. His plan was to a build a large-scale aquaponic system in Mareb province, to the east of Sanaa, where fish would thrive in ponds and solar panels would be used to generate electricity, while also drawing tourists.

The idea drew a standing ovation, though the prospects for success might seem remote - Mareb has been the site of continuing violence between military forces and aggrieved tribesmen who regularly sabotage oil and gas pipelines and electricity towers to extract concessions from the central government.

Other talks also outlined seemingly practical solutions for the country’s future. Abdullah Faris, for example, noted that Yemen faces basic infrastructure challenges that are almost unimaginable in the West: since there is little notion of addresses, calling the police to report the location of a crime, let alone calling an ambulance to your home, can be a monumental challenge. “Ninety-five percent of the Yemeni population has never received a postal letter,” he says. His solution is a website that could provide a unique 10-digit address - or Natural Area Code - to everyone in Yemen based on GPS coordinates.

But, for those who think that TED only offers the positive, Dr Kaled Alamarie, an environmental protection scientist from the New York City Department of Environmental Protection, delivered a dose of realism. “Water is becoming so scarce in certain areas that gun battles erupt,” said Alamarie, who emigrated from Yemen some three decades ago, and speaks now with a thick Brooklyn accent. Deaths from battles over land and water rights, he said, “results in the deaths of some 4,000 people each year, probably more than the violence in the south, the armed rebellion in the north, and Yemeni al-Qaeda terrorism combined.”

Technology, such as drip irrigation, would help, as would desalination plants along the coast, he said, but the costs to pipe that water to Sanaa, 2,250m (7,000ft) above sea level, are prohibitive. “There are,” he said, “no quick fixes and no one size fits all solution.”

The talks continued on similar themes, including hi-tech medical sensors that could, it was claimed, help extend the lives of the 97% of the Yemeni population who never make it past the age of 65.

Drone music

TEDx events like the one in Sanaa are affiliated with TED, but locally organized. They are an offshoot of the two, highly-successful annual conferences organized by TED itself. Since launching the idea of TEDx in 2009, there have been more than 4,000 events in more than 130 countries.

But, despite their success, TED – and what it stands for – is not without criticism. Some argue that the organization promotes saccharine visions, and ideas devoid of meaningful content or reality. Packaged into a maximum of 18-minutes, the talks allow for precious little analysis, let alone nuance, that characterizes real problems or solutions. At times TEDx Sanaa fell into the more easily parodied moments of TED world, such as the incessant clapping after each speaker (a TED attribute parodied by the satricial website the Onion, in a series of videos).

And, within Yemen itself, there were some doubts about the event. One activist, who did not attend, criticized the exclusiveness of the event, citing the application process, which required a Western-style resume, something many Yemenis were not used to.

As a result, most of the attendees were from the young, educated, urban elite, with a slight bias towards males.

Some also criticized the organizers for not live-streaming the event at Sanaa’s coffee houses, one of the few places in the city with reliable high-speed internet.

In the end, only a little over 300 people viewed the event’s webcast.

But, for many, the success of TEDxSanaa was simply that it took place: a decidedly progressive event at a time of enormous political change. The country is still struggling in the aftermath of last year’s anti-government demonstrations that pushed the country to the of civil war before a political deal led to 33 year President Ali Abdullah Saleh stepping down from power. The transitional government is now supposed to be paving the way for open elections next year, but political negotiations have been stalled for months.

And there are other problems. Foreign kidnappings have become so common that it is now something of a national joke (the far majority of the kidnapped are returned unharmed) and there is also growing criticism over US drone strikes, which are openly embraced by the current government. Yemen’s interim President Abd Rabu Mansur Hadi, in his first visit to Washington in September, marveled at drone technology, claiming that it was “more advanced than the human brain”. And just two days before the TEDx event, a reported US drone strike targeted suspected Al Qaeda militants in central Yemen, one of a series of attacks that has only escalated in recent months.

One hallmark of TED talks, however, is that politics like this are left out: no easy task in a country at the centre of ongoing global antiterrorism efforts. One of the event’s speakers, 23-year-old Ibrahim Mothana, has been a vocal critic of the US drone campaign in Yemen, writing a New York Times opinion piece in June, titled, “How Drones Help Al Qaeda”. But, on stage, Mothana decided to avoid the topic, focusing instead on local communities and leadership.

“The theme of the conference was inspiring hope and talking about drones is rather depressing,” he said.

That doesn’t mean that TEDxSanaa was droneless. One of the more popular moments at the event was a replay of a videotaped TED 2012 talk by University of Pennsylvania Professor Vijay Kumar on swarming drones, titled “Robots that fly...and cooperate.”

Though Kumar’s talk focused on small civilian drones that could be used in situations such as earthquake recovery, divorcing drones from the reality of their political and military applications is hard, even at TED. The video’s closing scene pictured a tiny band of the flying robots performing the James Bond spy theme.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on Future, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.