'It punched a hole through political correctness': How Eminem's The Marshall Mathers LP sent shockwaves through the '00s

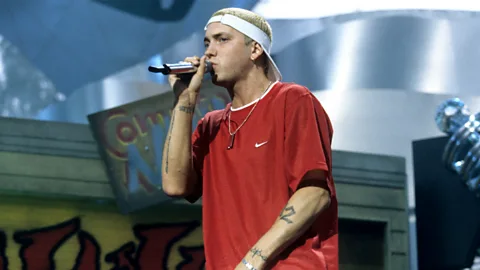

Getty Images

Getty ImagesTwenty five years ago, the rapper provoked outrage with his third LP, which shot him to superstardom, and was notorious for its offensive lyrics. Now it has become an even more divisive listen.

Eminem's third studio album, The Marshall Mathers LP, is almost instantly an act of provocation. The Detroit rapper, in the guise of his furious Slim Shady persona, uses this record's intro to encourage naysayers to go "sue me", setting the unapologetic tone for everything that follows.

Warning: this article contains offensive language and descriptions of violence

The first song Kill You then sees Eminem-as-Slim-Shady flow over an impish, stripped-back beat with the whirlwind ferocity of The Looney Tunes' Tasmanian Devil. Lyrically he boasts about getting a machete from OJ Simpson, assaulting his own mother, and being the one who "invented violence", daring outsiders to take these controversial words seriously. It's shocking to listen to, but the fact his nasal voice sounds like a mixture of a squeaky clown nose and a Midwestern court jester gives everything a cartoonish edge.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesReleased 25 years ago this month, The Marshall Mathers LP was Eminem's ticket to superstardom and, more broadly, a real inflection point for Western pop culture. This was a moment where a white emcee from Warren, Detroit, was suddenly the most debated artist on planet Earth. A celebrated anti-hero, who could provoke outrage while also shifting tonnes of hummable records in the process: MMLP went on to sell more than 35 million copies worldwide.

Eminem was the parent-advisory sticker provocateur who could include homophobic slurs in his raps – but somehow still sincerely perform alongside Elton John, one of the world's most famous gay musicians, at the 2001 Grammys. Entertainment Weekly's Will Hermes perfectly summarised these palpable contradictions in an early MMLP review, calling the album: "Indefensible and critic-proof, hypocritical and heart-breaking, unlistenable and undeniable."

The album's intent

Anthony Bozza, Rolling Stone journalist and author of the book, Whatever You Say I Am: The Life and Times of Eminem, recalls that, as offensive as some of The Marshall Mathers LP's lyrics were, Eminem represented something much deeper than just blind rage. As he sees it, the rapper's Slim Shady alter-ego had essentially been conceived by Eminem to punch a hole through the political correctness of the era.

"Political correctness has been a concept in the media and academia since the 1930s, but it became a huge talking point in the '90s and early-'00s," he explains, noting that Eminem was part of a wider "push back against it in music and entertainment" at the time.

Everyone, no matter how popular or vulnerable – from puppies to Christopher Reeves to pop stars including boyband N-Sync and Britney Spears – was a target inside Eminem's crosshairs.

Slim Shady was a sociopathic character envisioned as a sort of MTV generation Frankenstein's monster, out to take down everything in culture that was considered middle-of-the-road. "Slim Shady is the name for my temper or anger," the rapper explained in one early interview. "Eminem is just the rapper, Slim Shady is the attitude behind him."

Not everyone accepted this rationale, however. Lynne Cheney, the wife of former US Vice President Dick Cheney, told a 2000 Senate hearing that Kill You specifically was "promoting violence of the most degrading kind against women".

But the shock tactics of the lyrics aside, musically The Marshall Mathers LP made just as big of an impression. Following its release, many subsequently compared Eminem to Elvis Presley in how he deftly adapted a black artform, rap, and popularised it in Middle America.

However Craig Jenkins, a music critic for Vulture magazine, believes there was a fundamental difference between these two artists. "It was always obvious that whiteness put Eminem on radars that not every other rapper was landing on," the music writer explains. "But the big difference between Em and Elvis is the latter was somewhat trying to make himself more palatable to more people, but the former is defined by the fact he seems to hate all the kinds of people there is to hate."

Alamy

Alamy"MMLP took over the zeitgeist and changed the way mainstream white people and white cultural critics perceived hip hop," agrees Bozza, adding also that his sheer force of personality won over many fans at the time. "Following the excitement and popularity of grunge and alternative rock in the mid-'90s, bland record company fodder rock bands took over the airwaves. But in 2000 there was a huge section of the population who just didn't see themselves in what they were being told to like.

"It makes complete sense, then, that at the turn of the century, professional wrestling had a huge boom in business, thanks to Stone Cold Steve Austin; South Park was massive; as was aggressive and lewd nu-metal like Limp Bizkit and Korn. Eminem's rebellion, snark, and inappropriateness were all definitely in."

The Marshall Mathers LP was the perfect record for this particular moment of disaffection. "Will Smith don't have to cuss in his raps to sell records / well I do, so fuck him and fuck you too!" was perhaps this angry, peroxide blonde's mission statement from MMLP's massive single The Real Slim Shady – filthy yet sharp, the song's technically gifted toilet humour is like South Park's Eric Cartman if he carried a library card. When the song was performed live at the MTV VMAs shortly after its release, Eminem was flanked by hundreds of lookalikes in a move that hinted at his total mainstream ubiquity.

Whether rapping about corrupt priests (Criminal) or parents allowing their young children to wear make up (Who Knew), Eminem was that rare artist able to effortlessly mirror underlying US social tensions, believes Jenkins. Referencing a MMLP moment where a cheeky Eminem criticises President Bill Clinton for his affair with intern Monica Lewinsky, Jenkins claims: "On the Marshall Mathers LP Em sliced through the veil of American decency and saw that it was all a front!"

Eminem's origin story

To understand how Eminem came to define the early-2000s zeitgeist with The Marshall Mathers LP, you have to rewind a few years to his entry into the music business. Having grown up with a single mother in a trailer park in a predominantly black neighbourhood in Detroit, a young Marshall Mathers, who was bullied at school for being poor, found solace in the bulletproof raps of artists like Ice-T and LL Cool J. "We were on welfare, and my mom never ever worked. I'm not trying to give some sob story, like, 'Oh, I've been broke all my life', but people who know me know it's true," Eminem revealed in a 1999 interview with Spin magazine.

He also explained there were times when friends had to buy him shoes, declaring: "I was poor white trash, no glitter, no glamour". This was a white rapper who was truly part of the US's tragic inner-city struggle, and the antithesis to Vanilla Ice, who had come to the fore in the early-'90s and was criticised for embellishing his street ties. Eminem wrote his first lyrics as a teenager, graduating to cult status within Detroit's battle-rap scene, where the witty emcee would astound opponents with his jugular-aiming freestyles.

This period was later immortalised in the 2003 Oscar-winning, semi-autobiographical film 8 Mile, which bagged Eminem a best song Oscar for Lose Yourself, and established him as hip hop's Rocky Balboa. He often flipped the slur of being "white trash" on its head in these early battles, turning his biggest weakness into a verbal dagger.

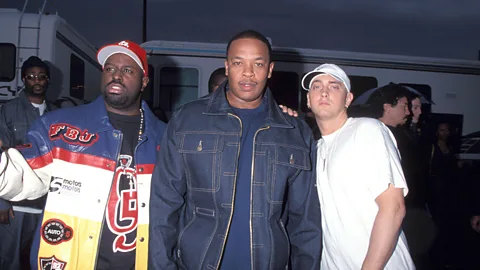

After achieving success in 1997 at the celebrated battle-rap competition, The Rap Olympics, in Los Angeles, Eminem caught the attention of Interscope Records intern Dean Geistlinge, who passed his demo tape over to an instantly impressed Dr Dre. They quickly put out the 1999 debut, The Slim Shady LP, on Aftermath Records. Although it was a commercial success, going on to sell 10 million copies worldwide, and a hungry Eminem chewed through its Dr Dre beats like an angry pitbull – see infectious hit single My Name Is – it's fair to say the lead artist was still a little rough around the edges.

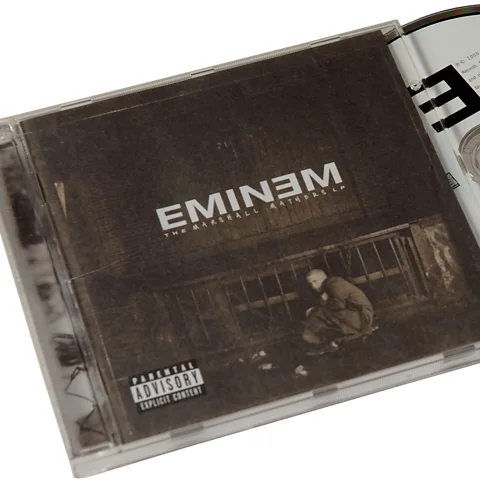

Alamy

AlamyHowever, with its follow-up a year later, it felt like Eminem was becoming more and more of a potent generational voice, with a clearer three-dimensional backstory. The original artwork for The Marshall Mathers LP sees the rapper sitting on the porch of his down-at-heel childhood home, the windows all boarded up – a portrait that spoke of a fragile American Dream and an artist who represented hope to forgotten working classes, both black and white.

His songwriting had become much more ambitious too, finding more powerful ways to tap into the directionless anger of a lost generation of millennials. Indeed, it felt like Eminem set the tone of a new phase for white rappers, where they could be respected for their talent within a black music culture which, bar a few notable exceptions (Beastie Boys, 3rd Bass), had previously tended to reject them as try-hards. It's fair to say a co-sign from Compton-raised Dr Dre, who had made anti-police anthems as a member of NWA, brought a different audience to Eminem.

"Eminem's insouciance and darkness were the love languages of the '00s kid, who was just old or jaded enough to be embarrassed by respectable teen pop stars," explains Jenkins of the initial period when The Marshall Mathers LP was released. "Back then you saw a crassness for crassness' sake everywhere, from radio shock-jock broadcasts [like the Howard Stern show] to antisocial pop chart sensations like Eminem," he adds.

One of the album's most prescient songs is The Way I Am, where Eminem raps over doomsday church bells with an astonishing level of precision despite all the heavy emotion underpinning his words. Eminem poignantly complains about not being able to go to a public bathroom without being harassed by fans, and being strangled by commercial pressures from suits within the music industry: "I'm so sick and tired of being admired / I wish I would die or be fired!"

In the music video to The Way I Am, he's in literal freefall after jumping off a skyscraper. Given the praise that modern pop star Chappell Roan recently received for criticising invasive paparazzi and fans who overstep the mark in public, this song feels ahead of its time in what it was diagnosing. This ability to make you feel invested in a rags-to-riches personal story (from trailer park to international fame) was one of the reasons The Marshall Mathers LP crossed over like it did, argues Holly Boismaison, a musician and writer who is currently working on a book about Eminem, Guilty Conscience, which considers the social impact of the artist's discography.

"Eminem has a non-clichéd story to tell about himself – [he's] vulnerable, with this love-hate relationship with masculinity, a lack of interest in empire building, and a giddy playfulness that comes through even in his defiance," she says. "He deals with his personality by turning the characters in his musical universe into a funhouse mirror of himself."

Boismaison claims that The Marshall Mathers LP's music, largely produced and mixed by Dr Dre, is also much more layered than history remembers: "[The album] uses sound textures from Max Martin's teen pop that are stripped right back and given evil, stop-start rhythms. Many tracks even use rockabilly guitar plucks that evoke Elvis directly. And yet Eminem's using those pop beats to diss [fellow] stars like he's 2Pac rounding on one of his millions of enemies. It's an album that manages to incorporate black culture into a white pop context without sanitising [it]."

A quarter of a century later and few would argue against the project's most powerful song being Stan. Built around haunting rainfall effects, wounded yet airy vocals courtesy of Dido, and a bassline that groans in a depressed stupor, this song tells the story of the titular Stan, a crazed fan with a parasocial relationship towards Eminem himself. Rapping from the perspective of a drunk Stan, Eminem spits: "I can relate to what you're saying in your songs / so when I have a shitty day, I drift away and put them on!" But the character gets progressively more agitated, culminating in a horrifying climax which sees him driving a car, with his pregnant girlfriend locked in its trunk, off a bridge.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAside from being as vivid as any Hollywood thriller, Stan was ahead of its time in highlighting the toxicity of feverish musician fandoms, and its lyrics foreshadow the noise of contemporary social media, a place where there's endless reckless comments shared about celebrities. Indeed, "stan" has now entered common parlance, referring to someone who is an obsessive super-fan of a particular artist or celebrity – although not typically as sinister as Eminem's protagonist.

"I think Stan speaks loudly to its era of Columbine and the Oklahoma Bomber, [with] its exploration of what makes a fragile everyday person commit a headline-grabbing murder," argues Jenkins.

How its offensiveness has aged

As someone who is gay, Jenkins admits he has split feelings about The Marshall Mathers LP, which is an album where a particular homophobic slur is used with reckless abandon. "There was a lot in the music that made me wince. But I don't subscribe to the notion that Em was much worse on a homophobic index than everyone else [in rap] at the time," he says.

"For a straight '90s male there was little worse than being seen as gay, or 'less than a man', as the logic suggested. The thought is in everything. I winced in Common and Black Star records. I winced at A Tribe Called Quest and Brand Nubian and Public Enemy records."

Eminem has defended his use of homophobic slurs. In a 2013 interview, he said: "Not saying it's wrong or it's right, but at this point in my career [MMLP] man, I said so much shit that was tongue-in-cheek. I poked fun at other people, myself. But the real me sitting here right now talking to you has no issues with gay, straight, transgender, or women at all."

The fact horror boogeymen like Leatherface and Norman Bates are referenced throughout MMLP also hints Eminem is storytelling in the tradition of horrorcore – an especially gothic, violent style of rap inspired by horror films. On track Who Knew, he addressed controversy around his lyrics and their alleged bad influence head-on, suggesting bad parenting was to blame for out-of-control millennial American teenagers, not fantastical bars from Slim Shady: "Don't blame me when little Eric jumps off the terrace / you shoulda been watching him, apparently you ain't parents".

As a woman in her early 30s, Boismaison says she is especially conflicted about a particular track, Kim, where Eminem graphically describes murdering his ex-partner. "Kim is a masterpiece, a visionary work of art about the stupidity and impotence that animates male violence, down to the moment where Slim starts screaming at the radio and the driver cuts him off," she claims. "But it's also impossible to separate it from the fact that putting the song out at all qualifies as abuse."

The Marshall Mathers LP has certainly only become a more divisive listen a quarter of a century later. In an era where artists are noticeably more aware of not causing offence, Eminem's callous, abusive persona feels like an even greater shock to the system.

Alamy

AlamyIts popularity has not dimmed however, as evident by its massive streams; it's surpassed five billion on Spotify alone and the Stan music video has nearly 800 million streams on YouTube. It also had a notable impact on the next generation of rappers, with Kendrick Lamar, Nicki Minaj, and the late Juice WRLD all famous fans. "MMLP's popularity endures because it's a stone-cold classic. This record in particular captures the insanity of his life and career as he became the artist we know today. The album is a snapshot of that rise and time," says Bozza.

The veteran music journalist wrote a cover interview with Eminem for Rolling Stone around The Marshall Mathers LP release cycle and the album has stuck with him. "I crack up at the shrieks, the head-spinning rhymes, the chainsaw sounds, and the insane imagery," Bozza says, adding that "I also grin because I have a personal connection to the song, Kill You" in which Eminem jokes about the idea of his hyper violent persona gaining a Rolling Stone cover. "Well, I wrote that Rolling Stone cover."

He also believes that in an era where artists of all kinds are striving to avoid controversy for fear of cancellation, the album's unfiltered nature, for all its offensiveness, will continue to attract new fans. "Marshall Mathers LP was Eminem at the end of this rope with nothing to lose. This energy remains attractive, particularly today."

Not all critics agree, however, with some re-evaluating The Marshall Mathers LP and its content. "Eminem's music plays like a schlocky horror movie, mixed with documents that spilled out of a family court, and extracts from a bratty teenager's diary," wrote music journalist Dean Van Nguyen for The Irish Times back in 2017. "His shtick was built on shock value and kids were drawn in like Icarus to the Sun. But what happens when the terrible teens grow up? Eminem's gimmicks hold up about as well as a Crazy Frog single."

Whatever side you agree with, there's not many albums from the year of the Millennium Bug that are still so feverishly debated or able to provoke so many conflicting raised voices. In the 25 years since The Marshall Mathers LP, Eminem has put out a lot of albums of varying quality, but none that carry the same sting.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.