Why we're 'living in the golden age of the doppelganger'

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIt's been a year of lookalikes – but the lure of the "second self" goes way back to the folklore of the Irish "fetch" and the Nordic "fylgja", and to the writings of Edgar Allen Poe and Sigmund Freud.

In March of this year, someone with the feline eyes, blonde hair and high cheekbones of Kate Moss walked the catwalk at Paris fashion week. But it wasn't Kate Moss. Online there was confusion. "Isn't that just Kate Moss?" ran a typical comment. A disbelieving, "that is Kate Moss," was another common refrain. For a savvy few, the gait gave it away as someone other than the famous British supermodel – it was in fact Denise Ohnona, a Moss lookalike from Lancashire.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHigh fashion seems to have sparked a trend. Later in the year, the floodgates opened to a wave of lookalike competitions. First came the moment for those who fancied themselves the spit of Timothée Chalamet to gather in New York's Washington Square Park. Then Dubliners flocked to make the case that they looked like Paul Mescal. Next came a competition for Harry Styles lookalikes, then Dev Patel, followed by The Bear star Jeremy Allen White, Zayn Malik, Zendaya, and so on, with others slated to take place throughout December.

While this recent spate has felt very of-the-era and has been global in reach – each one spreading with breakneck-virality – the lookalike competition is not a modern innovation. Charlie Chaplin once came third in a contest to find his own likeness in the 1920s, according to his son, Charlie Chaplin Jr, who wrote in his book My Father, Charlie Chaplin: "Dad always thought this one of the funniest jokes imaginable." Chaplin himself reportedly denied the veracity of the story. What is more testifiable is that Dolly Parton entered one of hers, recalling in her memoir how she "got the least applause but I was just dying laughing inside".

It's been the busiest year for lookalikes that Andy Harmer can remember. A David Beckham lookalike, Harmer runs a lookalikes agency, and has more than 3,000 people on his books who each share something of the essence of someone famous – from Isambard Kingdom Brunel to Rihanna and Ariana Grande. Moss lookalike Ohnona is one of the jewels in his agency's crown.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBut while lookalike contests have been the most widespread and talked about examples of doubling this year, they have not been alone in bringing themes of the doppelganger into the spotlight. From films to TV and literature, doppelgangers have been populating the ether.

According to Adam Golub, a professor of American Studies who is writing a book about the doppelganger in American culture: "There's no question that we're living in a new golden age of the doppelganger." While they ebb and flow in popular culture, "they're definitely back with a vengeance," he tells the BBC.

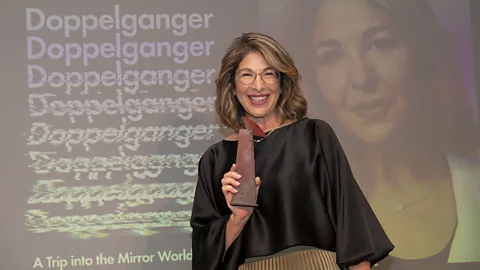

In June the Canadian writer and activist Naomi Klein won the inaugural Women's Prize for Non-Fiction for Doppelganger: A Trip into the Mirror World, in which she submerges herself in the conspiracy-saturated world of a woman she was chronically mistaken for online, the controversial writer Naomi Wolf. It follows on from a post-pandemic novel by Deborah Levy in which the central character travels the world encountering a doppelganger. "She was me and I was her. Perhaps she was a little more me than I was," she writes in August Blue.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSo what actually is a doppelganger? "An easy way to think of a doppelganger is it's a non-biological second self," says Golub. "It's an identity double that is not related to you," Alia Soliman, lecturer of cultural studies and author of Doppelganger in Our Time: Visions of Alterity in Literature, Visual Culture, and New Media, tells the BBC. "The term was coined by Jean Paul Richter."

The second self

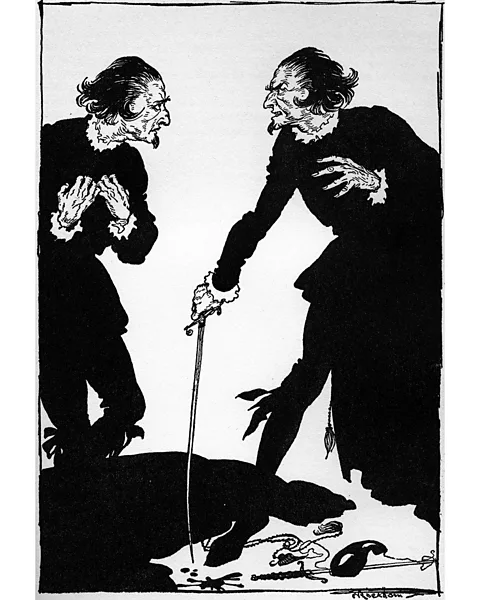

Culture new and old has explored themes of identity, death and the symbiotic nature of good and evil through the idea of the doppelganger. It has been the subject of art, from René Magritte's surrealist paintings to those of Pre-Raphaelites like Dante Gabriel Rossetti, whose 1860-1864 painting How They Met Themselves depicted a pair of lovers meeting their doubles in a wood.

In its early literary form, says Soliman, referring to works such as Adelbert von Chamisso's Peter Schlemihl (1813), Edgar Allan Poe's William Wilson (1839), Fyodor Dostoevsky's The Double (1846), and Robert Louis Stevenson's The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886), the doppelganger "takes the shape of a ghostly self or a shadowy reflection that torments the first self". Almost all the early literature, she says, "sees the destruction of the original as well as the second self".

The same can be said for "folkloric renditions of the apparition, such as the Irish fetch and Nordic fylgja, [in which] the appearance of the doppelganger foreshadows the end of life or the approach of harm". The fylgja is seen more as an alter ego, typically in animal form, more often seen in sleep, while the fetch is thought of as a spirit-double. In Northern Irish poet Ciaran Carson's 2008 poem The Fetch, he wrote: "To see one's own doppelganger is an omen of death… Shelley saw himself swimming towards himself before he drowned. / Lincoln met his fetch at the stage door before he was shot," referencing the alleged encounters with doubles just before the deaths of both the poet PB Shelley and the US President Abraham Lincoln.

Fitzwilliam Museum

Fitzwilliam MuseumIn Freud's 1917 essay, The Uncanny – a seminal work in the doppelganger canon – the double is "uncanny", which Freud describes as "belonging to all that is terrible – to all that arouses dread and creeping horror".

The doppelganger, then, was something to be feared. "It wants to take your identity," says Golub. This theme is explored in the debut film by JC Doler, The Fetch, which was nominated in the Dark Matters Feature category at the recent Austin Film Festival. It's there, too, in Coralie Fargeat's The Substance, in which a middle-aged Hollywood actress played by Demi Moore has to watch as her younger clone, played by Margaret Qualley, lives the life that she once had. And the theme can be seen with most clarity in the popular sci-fi trope of body-snatching. "You might be replaced by an alien doppelganger or a robot doppelganger, or some kind of supernatural being, an evil twin from another dimension," says Golub. "Generally speaking, in the stories we tell about doppelgangers, our lookalike is not welcome."

Things shifted, according to Soliman, in the second half of the 20th Century, when portrayals of the double "significantly altered in form, content, and message". Cut to today, and the double is seen differently: just think of Chalamet turning up to take selfies with contestants at his own lookalike contest. What Soliman refers to as "the new double" is altogether less malign and maligned. This new double sees "depictions in which the meeting between self and double changes in structure and significance, carrying a redemptive message". The young clone in The Substance is more of an irritation than a dreaded adversary. And lookalike contests are a bit of good old-fashioned fun, quaint and wholesome. There is an absurdity and a humour in seeing people who look alike.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn this new context, it is small wonder that people are actively seeking their doppelgangers via a wealth of specially designed apps. Or that one of the most high-profile doppelganger projects of recent times has been the photography project of Canadian artist François Brunelle, who, spurred by his own likeness to Rowan Atkinson's television and film character Mr Bean, has found hundreds of lookalikes, and created a body of work that proffers a message of hope and togetherness. "We are reimagining our relationship to doppelgangers," says Golub. "We are writing a happier ending to the story, one in which we kind of find our stranger twin and we bond with them – or we win a celebrity lookalike contest."

More like this:

• Gaudy or iconic? How leopard print took over

Experts have thoughts about what is driving this paradigm shift. Soliman looks back to the introduction of the world wide web in 1993, which, she says, "gave way to a new array of technologically induced fixations, one of which is the search for our digital doppelganger". With the internet, that search became so much easier than ever before.

"The opportunities and complexities resulting from visual and virtual innovation in social media have impacted the culture of the double self," says Soliman. "The self is given far easier access to its double."

"Why aren't we scared of these things that somehow represent something we should be repressing?" asks Golub, harking back to the original doppelganger. He thinks it is because, in the digital age, we are all used to having dual, sometimes multiple identities: physical selves and online selves, different voices across different social media platforms. He says that we are "turning to this kind of playfulness, this fun, this doppelganger fandom" as a way to navigate that. "Perhaps as a way to make us feel whole again… to find a version of yourself that's not out to steal your identity or take something from you, but might actually just want to take a selfie with you and enhance your life."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesDoppelgangers have become about connection to an offline community. "Social media sort of pushes us all out into our own weird bubbles, and the idea that there's someone just like us out there doing life differently [is a] really warming idea," the psychoanalyst Anouchka Grose, who has had the experience of being repeatedly mistaken for an actor in UK TV soap Hollyoaks, tells the BBC. It fits that young people in particular – perhaps especially atomised by extensively online identities – might be seeking out connection via offline lookalike contests. And that these meetings seem to have taken place in the spirit of wholesome country fairs – digital virality to one side – with lo-fi posters inviting people to attend and minimal cash prizes for winners.

At the other extreme of the doppelganger phenomenon there is the spectre of deepfakes on the digital horizon – that is, fake doubles that can fool us into thinking that they are the originals. But that will not long remain the case. "AI is going to disrupt a lot of things in our lives," says Golub. This moment of cosy playfulness around the doppelganger may turn out to be short-lived, "once we start to see some of the real dangers of what [deep fakery] can do," he adds. "I think we should enjoy our fun while it lasts," he says.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.