'It's time to retaliate in song' – Why NWA's provocative 80s rap became an anthem

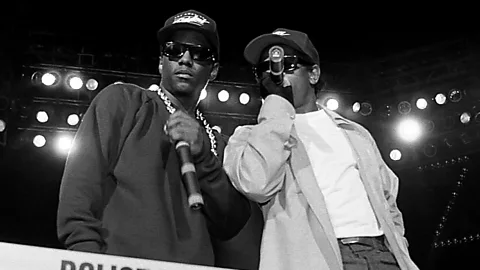

Getty Images

Getty ImagesNWA's landmark album Straight Outta Compton was released on 8 August 1988, bringing the sound of gangsta rap to mainstream America. In History revisits an interview with the young rap crew as they tried to deal with the success and fallout of the record.

"You are now about to witness the strength of street knowledge" is the line that opens Straight Outta Compton, the title track that kicks off NWA's multi-million selling debut. It sets the scene for an hour of incendiary rhetoric and thrilling sonics, blending bravado, misogyny, homophobia, and a provocative message that travelled far beyond their home city of Compton, in South Central Los Angeles.

Warning: This article contains language that some may find offensive.

Fuck tha Police is the explicit protest song that put NWA on the map. An urgent howl of fury against police brutality and racial profiling, it led the FBI to complain to their record company that it encouraged violence and disrespect of the law. Told as a parody of court proceedings, rapper Dr Dre turns judge and hears his band mates Ice Cube, MC Ren and Eazy-E present a forceful case for the prosecution of the Los Angeles Police Department.

What follows is a rap sheet that includes police who "think they have the authority to kill a minority", cops who assume all young black men are "selling narcotics", and black officers who are just as guilty of mistreatment.

For Ice Cube, the group's initial breakout star who wrote more than half of the album's lyrics, it was a "surreal fantasy" song of revenge. He told the BBC's Late Show reporter Mary Harron: "I'm sick of getting hassled. I was tired of seeing my friends come home with scars and stuff, police beating them up for anything and everything, so I was like, 'Yo, it's time to retaliate, you know, it's time to retaliate in song'. 'Let's hurt their feelings' type of thing, you know? You can't do it physical, but we can do it on this record."

Dr Dre, the group's production mastermind, believed they were merely reporting on something that was there in plain sight. He told the programme: "Everybody's thinking the same thing but nobody has really the heart to say it, you know, and we say it. Everybody is saying 'fuck the police' but nobody's saying it to the public, and we did."

In History

In History is a series which uses the BBC's unique audio and video archive to explore historical events that still resonate today. Subscribe to the accompanying weekly newsletter.

The song would become an anthem during the 1992 LA riots, sparked by the acquittal of four white police officers on trial for beating black motorist Rodney King, who had been stopped for speeding. Four of the officers who pulled him over hit him more than 50 times with their batons, kicked him and shot him with stun guns. The attack was caught on camcorder by a nearby resident in grainy black and white. It was evidence of the police brutality that the black community had been complaining about for decades. Tensions over persistent race and economic inequalities boiled over, leading to days of looting and burning, more than 50 deaths and $1bn in damage to the city.

'Reckless' or real?

Almost three decades later in Minnesota, the death of George Floyd in 2020 at the hands of police was also filmed by bystanders, now on mobile phones. Protests erupted in cities across the US, and later, around the globe under the banner of Black Lives Matter. This time, in contrast to NWA's blunt instrument of rage, the controversial slogan Defund the Police became part of some activists' push for change. Its advocates called for police budgets to be slashed and funds diverted to social programmes to avoid unnecessary confrontation and heal the racial divide.

By that time, the artists formerly known as "the world's most dangerous group" were so respectable that they had been mythologised by Hollywood in the 2015 biopic Straight Outta Compton. A year later, they were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame by rapper Kendrick Lamar, who represented a new generation of Compton hip-hop talent. Lamar told delegates that NWA had "proved to every kid in the ghetto that you could be successful and still have your voice while doing it". In an echo of history, his hopeful 2015 song Alright would itself become a Black Lives Matter protest anthem.

In January 1990 when the NWA interview was broadcast, the band was in the crossfire of criticism from many angles. Lyrics such as "when I finish, there's gonna be a bloodbath of cops in LA" outraged an FBI assistant director Milt Ahlerich, who issued a letter to NWA's record label saying the song "encourages violence against and disrespect for the law enforcement officer".

Others saw NWA's lyrics as reckless and irresponsible, such as Spin magazine hip-hop writer Bönz Malone, who told the BBC that while they claimed not to glamorise violence, "their videos with the guns and the fancy cars and the gold chains" told a different story. Jamie Foster Brown of African-American entertainment magazine Sister 2 Sister compared them to "shoot-em-up cowboys". She told the BBC: "I mean, they don't understand the magnitude of death, the pain of really shooting someone. I don't think they grasp that. This is serious business, to have a gun."

Dr Dre rejected claims they were romanticising gang violence. "There's nothing in our records that's not real; everything that's in our records did happen or could happen," he said. For Eazy-E, the band refused to take a moral stand on the scenarios depicted in their lyrics. He told the BBC: "If you decide to be a gangbanger… you might end up dead or you might end up in jail. We're not telling you to go do it. We're not telling you not to do it. We're, like, neutral. We're in the middle. If you do it, hey, that's on you."

Village Voice critic Greg Tate told the BBC that when he first heard the Straight Outta Compton track Gangsta Gangsta, it seemed to be endorsing black-on-black crime and drive-by shootings. Over time, he said, his interpretation softened, "until I really saw them as dramatising the Compton reality". According to Tate, there was a stereotype that "hip-hop only comes out of misery and poverty and degradation", but most popular rappers at that time, including NWA, "come out of the black middle-class".

More like this:

Ice Cube conceded his background "wasn't all that terrible, but I've seen terrible things and I've heard terrible things that I've taken to my mind". He added: "I boil it up like a bowl of stew and it comes out in these words and I take so much in my mind, I get angry. So when I come off when I rap, it sounds like I'm just angry, pissed off." He said he could only create lyrics from his point of view as a young black man: "When I write, I want you to close your eyes and picture this happening, you know?"

At the time the interview was broadcast, Ice Cube had just announced he was leaving NWA to launch his solo career. He said the trappings of his success had recently attracted attention from police officers who stopped him while driving and ordered him out of his car.

"I'm wondering if I was in Beverly Hills in a BMW with a different colour of skin, would they ask me what gang am I in or where's the guns or where's the drugs? You got to ask yourself those questions when you get stopped.

"But I just go through it because I just tell them I'm legal. You can search the car all day. You ain't going to find anything but gold and platinum records."

--

For more stories and never-before-published radio scripts to your inbox, sign up to the In History newsletter, while The Essential List delivers a handpicked selection of features and insights twice a week.