In History: Suffragettes speak about direct action and their brutal treatment

Getty Images

Getty Images"The object was to create an absolutely impossible condition of affairs in the country." In exclusive archive BBC interviews, two activists look back at their turbulent time fighting for women's rights – from window-smashing and arson to hunger strikes and force feeding.

Lilian Lenton knew early on in her life how she felt about inequality. As a child, she was "extremely annoyed at the difference between the advantages men had and boys had, and the ones girls had", she told the BBC in 1955. "Everybody wanted a boy… and it irritated me simply, enormously. And then when one grew up and saw the differences in opportunities that men had, well, of course that just increased that feeling," she told the interviewer.

Lenton, who was born in Leicester in 1891, was the eldest of five; her father was a carpenter-joiner and her mother a homemaker. Having trained as a dancer, as a young woman she attended an open-air meeting of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU), where the speaker explained that "lunatics, criminals, paupers and women may not vote". She immediately joined up, she says, and was soon attending "poster parades" through London.

In March 1912 she and fellow members, armed with hammers, participated in a window-smashing campaign in London – and she was jailed for two months. In July 1912, following the arrest of the group's leader, the suffragettes turned to arson. Lenton and Olive Wharry conducted a series of arson attacks, and were arrested. The arson attacks were initially extremely high-risk for the activists, though they were careful never to put the public at risk. "We only just got out in time on one occasion," said Lenton.

In prison she, along with many of her fellow protesters, embarked on a hunger strike. She told the BBC that she had been striking "for release, on the grounds that they had no right to imprison women for breaking man-made laws".

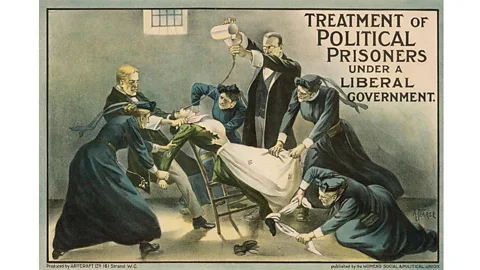

Alamy

AlamyBefore long, the women were being violently restrained and force-fed by order of the prison authorities – a brutal and inhumane procedure. In the interview, Lenton looks and sounds haunted by the memory of it. "The forceful-feeding process was really extremely unpleasant," she says, with clear understatement. "I don't like talking about these things… I've never told people."

Lenton nevertheless goes on to describe in graphic detail the invasive and barbaric process which – in her case – led to her becoming dangerously ill with pleurisy and double pneumonia, caused by particles of food entering her lungs.

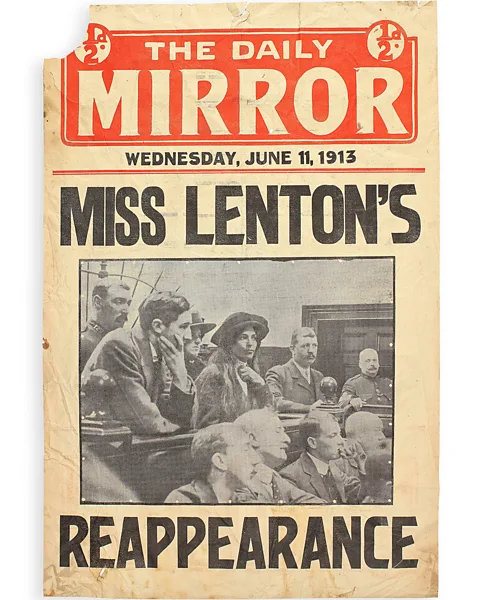

When she became seriously ill, she was released from prison, but the case caused outrage among the general public. The home secretary denied that Lenton had been force fed, claiming that her illness was in fact caused by her hunger striking – a claim that was disproved by official papers that recorded her force feeding. The public outcry intensified when a prominent surgeon wrote to the Times expressing his ethical concerns.

A few months later, Lenton was arrested again over an arson attack in Doncaster carried out with 18-year-old local journalist Harry Johnson. In the same year, an act was passed in Parliament which became known as the Cat-and-Mouse Act. According to this, any woman prisoner who was hunger striking should be released when she became seriously ill, and then re-arrested when she had recovered. Lenton was rearrested several times, and then was let go several times due to the ill effects of hunger striking.

When she was out of prison Lenton "went about as a normal person" and would "try to escape the detectives", she told the BBC. "Whenever I was out of prison my object was to burn two buildings a week. The object was to create an absolutely impossible condition of affairs in the country, to prove it was impossible to govern without the consent of the governed."

Lenton later received a hunger strike medal for valour from the WSPU.

In 1914, with the outbreak of World War One, the WSPU suspended their militant campaign, and focussed instead on the war effort. During the war, women took on jobs traditionally done by men, proving resoundingly that they could do them just as well, and so helping to silence any remaining arguments against women's voting rights.

Bonhams/ Votes for Women: The Lesley Mees Collection 2023

Bonhams/ Votes for Women: The Lesley Mees Collection 2023After the end of the war in 1918, the Representation of the People Act was passed, allowing the vote to women aged 30 or over who met certain property criteria, or who were married to a property holder. Lenton was not impressed. She said: "Personally I didn't vote for a very long time because I hadn't either husband or furniture, although I was over 30." It wasn’t until 1928 that equal voting rights were achieved.

Deeds not words

The tactic of the suffragettes was to demand – not ask – for their rights. "Deeds not words" was the motto of the WSPU, created in 1903. Its founder Emmeline Pankhurst, who had been a member of a Manchester "suffragist" group, had decided it was time for direct action by working-class women in order to secure the vote.

Heckling politicians was the extent of the protests at this time, and that "was considered really untoward", author Elizabeth Crawford told the BBC in 2018. That all changed in 1905, however, when Christabel Pankhurst and Annie Kenney were charged with obstruction, having interrupted a Liberal Party meeting. The two women chose to go to prison rather than pay a fine, and the attention brought to their cause by this action became an inspiration for the group.

"The idea of militancy then was ratcheted up over the years," Crawford said. "This was never overtly condoned by the leadership, but on the other hand they didn't condemn them. They just more or less said 'do what's necessary'."

Although dominated by educated and middle-class women, the women's suffrage movement also included many from less affluent backgrounds. In the Great Procession of 1910, a large demonstration in London staged by the WSPU, Votes for Women newspaper recorded "there were also sweated workers in poor clothes, and shirt makers, who fight daily with starvation". Efforts were made to gather support for the procession beforehand at meetings for laundry workers in north London, as well as via the canvassing of women in "factory and laundry districts" in south London.

Also interviewed by the BBC in 1978 was Elizabeth Dean, a suffragette from Manchester, who makes it clear that not all of her fellow activists were highly educated nor wealthy. For Dean and others, gaining the right to vote was part of a broader aim to avoid being just "child-bearing machines" like her mother, who died in her late-30s after having eight children. "Not all the women in the suffrage movement were fighting for degrees," she said. "We hadn't a chance of getting a degree, we were working women, and each of us had our own private thoughts of what we wanted, what we thought was just, and what we thought was worth fighting for."

In History is a series which uses the BBC's unique audio and video archive to explore historical events that still resonate today.

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news delivered to your inbox every Friday.