Noise, drugs and rioting fans: Inside the mayhem of Nick Cave's early days with explosive rockers The Birthday Party

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThese days, Cave is one of rock's elder statesmen. But decades ago, he started out in a band who caused chaos wherever they went, as new film Mutiny in Heaven recounts, writes Daniel Dylan Wray.

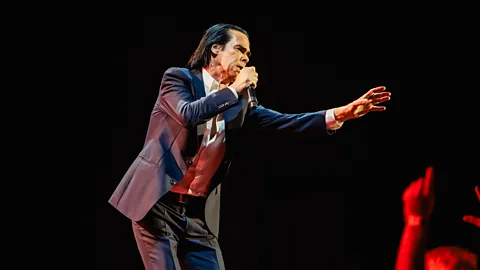

On his upcoming US tour, the Bad Seeds frontman Nick Cave – who for the last 40 years has been a revered songwriter known for writing music that veers from tender beauty to raging noise – will also undertake several intimate book events with fans in support of Faith, Hope and Carnage, the book he co-wrote with journalist friend Sean O'Hagan about his "inner life", comprised of long conversations between them.

More like this:

At these events, in intimate settings, Cave will speak candidly to devoted fans about a life and career that in more recent years has been shaped by grief after the tragic loss of his 15-year-old son Arthur in 2015. It's in stark contrast to the earlier relationship between Cave and his fans displayed in a new documentary, Mutiny in Heaven, which tells the story of his wild days starting out in his pre-Bad Seeds band, The Birthday Party.

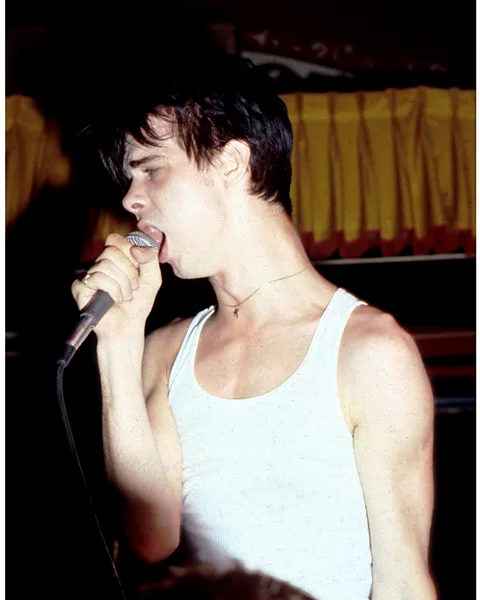

Alison Lea

Alison LeaThe Australian band landed in London in 1980 with a thud of disappointment. "We hated the place," the band's singer, Nick Cave, says in an archive interview featured in the film. "It was repellent", offers the band's guitarist, Rowland S Howard, who died in 2009.

A moderately successful band back home, originally known as the Boys Next Door, they left to conquer England and renamed themselves The Birthday Party – although they arrived broke, with drug addictions, and in a country that was as indifferent to them as they were disdainful of it. Within just three years the band would implode. But they left behind a short yet incendiary legacy and a catalogue of music that four decades on from the post-punk boom, remains a potent collection. While mimicked, their sound has arguably never been matched for its intensity.

Arriving in the UK

This whirlwind period is depicted in Mutiny in Heaven, a film that features rare and unseen archive footage, original artwork, unreleased tracks, live recordings, and studio footage of the band at work. "I wanted to create a world and drop the audience into it," the director Ian White tells BBC Culture. "To try and bottle that essence of the late 70s and early 80s." There's no gushing talking heads from fans; instead the band are placed front and centre. "When the material is that good, do you need someone else telling you it's good?" asks White. "It seemed superfluous to have commentators talking about how powerful the material was when you can see it."

The film traces their journey from Australia to England, where they ended up in a squalid bedsit they all shared. They had not found fame and fortune, but instead misery, destitution and malnutrition. Barry Adamson, who made his name with post-punkers Magazine in the late 70s and early 80s, but joined The Birthday Party for a few months on bass in 1982, tells BBC Culture: "I think they expected the streets to be paved with gold and with their names written everywhere but instead they landed in this pit of shit."

However, their dire situation as skint, alien outsiders from Australia with various dysfunctions and addictions, soon became something of a calling card that brought them a devout following. Feeling like they had been sold a lie from the UK weekly music magazine NME – considered something of a bible at the time for those interested in alternative music – around all the post-punk bands it was relentlessly raving about, the band found themselves surrounded by music they largely detested. "We felt that we were the only real rock band in the world," Howard says in Mutiny in Heaven. They harnessed this festering animosity and creeping anger, quickly garnering a reputation as a ferocious and explosive live band.

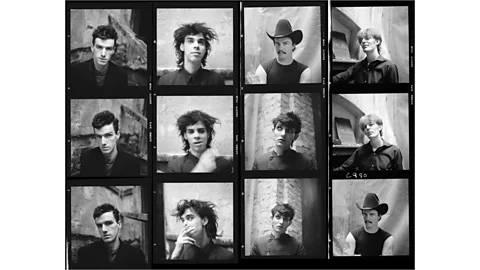

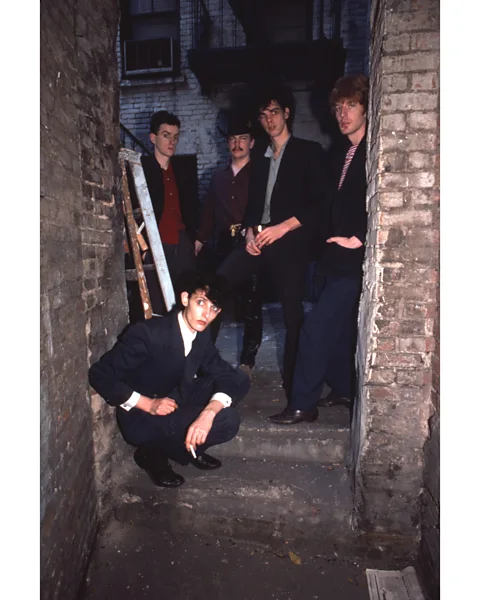

While many post-punk bands of the era favoured spiky angular guitar work with pop hooks buried in frenetic bursts of rhythm, the Birthday Party were less easy to categorise. Part screeching noise, part deconstructed gothic blues, with touches of psychobilly, art-rock and punk, they were a fiery, throbbing, volatile band, who also had a unique aesthetic – Cave looking like a human crow, bassist Tracy Pew a gyrating leather-clad cowboy, and Howard managing to somehow look both ghostly and vampiric. All this added to their quickly growing stature as outsider agitators. "I'd never heard a musical assault like that," Henry Rollins of Black Flag says in footage shot for Mutiny in Heaven that didn't make the final cut. "Then I saw a photo of them and they just looked like rock and roll."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe band would return home to Melbourne to record their 1981 debut album, Prayers on Fire. It was also here they would shoot the video for lead single Nick the Stripper. The theme was a carnival vision of hell, and they settled on a rubbish dump as a filming location. Hundreds of people turned up for the filming-cum-giant party. An old hippie who had taken LSD arrived as Jesus with a giant crucifix, another was dressed as an Egyptian eunuch, while Cave drunkenly prowled and howled his way through the crowds and flames in nothing but a loincloth with "hell" painted on his chest. In terms of a music video encapsulating the spirit, tone and energy of a band it is near-perfect: wild, messy, noisy, and inebriated almost to the point of total collapse.

Their combustible chemistry

Back in England, the band's fortunes were changing. Adamson recalls seeing them one week playing to an audience of around 12, but weeks later with queues around the block. This was a sweet spot for the band's guitarist and, later on, drummer Mick Harvey, as the shows were filled with people who had no idea what to expect but left feeling re-wired. "The whole thing felt greater than the sum of its parts," he tells BBC Culture "It was a beast unto itself and it was out of our control even though we were creating it. It was very hard for us to rein it in, and the audience could feel that too."

Rather than the band being centred around a frontman, each member's contributions were equally crucial. Cave was a visceral and guttural singer who had a feral ferocity to his delivery; Howard was an astonishing guitar player who could create atmospheric worlds to inhabit; Pew’s bass playing had a deep, rolling, menacing, purr to it; Phill Calvert’s drumming was skeletal but vital; while Harvey’s drumming when he replaced Calvert, and his guitar playing before that, were powerhouse contributions.

The groups' unique contributions to the band were also reflected in their diverse characters, resulting in an at times chaotic dynamic. Harvey was considered something of a backbone to the chaos, while Howard and Cave would often bicker and snipe, with Pew a source of constant unpredictability. Plus, factor in the array of drugs and alcohol consumed by different band members and this created a group of people operating at different speeds, moods, and in various states of toxicity from dusk to dawn. But for Harvey, who was largely sober, that unpredictability of temperament was a vital element. "Sometimes what made it really great was when all those weird combinations just were mixing together and bringing that level of unpredictability."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe tension the band would exude as they teetered between disaster and transcendence was also hugely attractive for Adamson. "In Magazine, there was a certain safety and formula," he says. "[But with the Birthday Party] you were in a continual conveyor belt of chaos," he says. "It sounds subversive but that seemed to work as a model – as a way to buck the system and be in your own creative world of craziness."

The mayhem of their gigs

However this chaos began to be mirrored in their audiences' behaviour, too. Shows became aggressive and violent, with people attacking the band, and riots broke out. Soon when they were heading out for a US tour, they were being described as "the most violent band in the world" – which of course only attracted more violence.

One night an audience member got on stage and began to urinate down Pew’s leg as he played, so Pew smashed the bass into his head in return. Another night, as recorded in a 1982 article in UK music weekly Melody Maker, a repeat offender for violence at Birthday Party shows, called Bingo, brought a bottle of methylated spirits with him. He took a glug, struck a lighter to his mouth, and breathed out a spewing ball of fire in an attempt to engulf the band. Deciding it was better to have Bingo on their side rather than fight him, they hired him as their personal minder to control the angry mobs.

Cave now has a reputation for having a loving and harmonious relationship with fans via his letter-writing platform The Red Hand Files, but this wasn't always the case. During one 1982 performance, a restless crowd began to fight as a panicked promoter rushed backstage to tell the band of the escalating tension. "Good. I hope the pigs kill one another," said Cave to Melody Maker in the same article that recalled Bingo's escapades.

But the violence killed part of the magic for Harvey. "When it would descend into tawdry fisticuffs it would destroy the tension that was building up," he says. "The violence was detrimental because it was a pre-prepared response – and that really wasn't what we were about. So we started playing a lot of slow songs but the irony was that those songs were quite intense, like really digging down into the dirt, so that didn't help. It made it worse."

The other band members felt the same – Pew told Melody Maker in 1982: "The band's just a little monster we've created that we don't seem to have any control over any more." Meanwhile, Cave seethed to NME in 1983: "I don't know of another group who are playing music that is attempting in some way to be innovative that draws a more moronic audience than the Birthday Party. This is not everybody, of course – just people I see from stage – there's always ten rows of the most cretinous sector of the community."

Throw in escalating drug use, personal and creative frictions between Howard and Cave, and, by 1982, the end was in sight. They relocated to Berlin to release what would be their final music, the superb Bad Seed and Mutiny EPs, but footage of the sessions shot by director Heiner Mühlenbrock depicts an ugly scene. Cave is nodding off from heroin use, communication is terse and tense, and there’s a general air of gloom that hangs ominously. Moments of creative brilliance are evident but there's palpable darkness. Harvey could sense it wasn’t going to be resolved and effectively pulled the plug on the band. "Something that explosive had to burn out as opposed to fade away," he says.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesPew died a few years later in 1986 at just 28 of a brain haemorrhage after an epileptic seizure. Before his death in 2009, Howard released records with Crime and the City Solution and These Immortal Souls as well solo albums, while Cave and Harvey went on to work together for decades in Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds.

But 40 years on from their messy, albeit somewhat inevitable demise, there are still very few bands as singular and visceral as the Birthday Party. "They made a mark on the world which was unique," says Adamson. "They came from such a different and extraordinary angle and despite the chaos, threat and subversion of it all there was also remarkable craftsmanship. It went beyond just conventional thrashing around."

Mutiny in Heaven is screening across the US and Canada throughout September and October 2023.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.