From Mariah Carey to Madonna – why divas deserve to be difficult

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe trope of the demanding, drama-loving diva is everywhere throughout the history of stage, screen, music and more. But a new exhibition celebrates the diva for what she really is – fabulous, writes Deborah Nicholls-Lee.

Mile-high heels, big hair and an extraordinary stage presence are not enough on their own. "It takes a long time to get to be a diva," Diana Ross once said. "You’ve got to work at it." But it's not clear what she means by "diva". Is she referring to her iconic status, having sold over 100 million records? Or to her reputation for temper tantrums and outlandish demands?

More like this:

Exploring the definition of diva-dom is the exhibition DIVA, just opened at the V&A, London. "The exhibition will show that there are many definitions and interpretations of a diva," lead curator Kate Bailey tells BBC Culture. But there’ll be no tabloid-style slating of Mariah Carey for allegedly demanding kittens and confetti at a Christmas lights launch, or of Jennifer Lopez for asking (UK TV show) Top of The Pops to redecorate her dressing room. "In our exhibition, we're reclaiming it as a positive," she says.

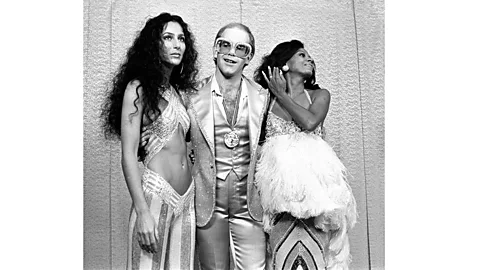

Bob Mackie

Bob MackieDIVA pays tribute to "the spectacle and the sparkle, the feathers and the flamboyant", says Bailey, with costumes taking centre stage. Headlining is the revealing "flame dress" designed by Bob Mackie in 1977 and worn by four divas: Cher, Tina Turner, Beyoncé and Ru Paul. There's Hollywood nostalgia with a fringed black dress worn by Marilyn Monroe in Some Like it Hot (1959), and high camp with Dame Shirley Bassey's hot-pink feathered dress and diamante monogrammed wellies, which graced Glastonbury's Pyramid stage in 2007. Other curios include a mother-of-pearl encrusted needlework box presented to opera legend Jenny Lind in 1848 in recognition of her charity work, and a throat spray belonging to legendary wartime warbler Edith Piaf (1915-1963).

The term "diva", meaning "goddess" in Latin, was originally associated with leading ladies, the prima donnas of the opera world, as a way to describe their divine talent. Around the time Italian soprano Adelina Patti (1843-1919) became one of the most recognisable faces in the world, the term began to suggest something more. Patti demanded high fees and amassed a fortune rarely enjoyed by a woman, investing much of this in an extravagant lifestyle (donning Parisian couture and setting up residence in a Welsh castle tended by 70 staff, for example), all of which helped sustain public interest, and kept the box office buzzing.

At the same time, divas of the spoken word were beginning to gain similar star status. Headstrong actor Sarah Bernhardt (1844-1923), whose tantrums were tolerated by theatre companies due to her unparalleled ticket sales, was a master of melodrama both onstage and off. An eccentric hedonist who wore a hat topped with a stuffed bat, kept a menagerie of exotic animals, and notched up a long list of highly distinguished lovers, she moulded her own image and set her own agenda, marketing herself through the artwork of Alphonse Mucha, and building up a cult of celebrity.

The birth of the motion picture at the turn of the century saw many stage stars move into film, reaching vast and diverse new audiences, and magnifying their influence on popular culture. Among them was Bette Davis (1908-1989), a striking actress with pencil-thin eyebrows and saucer-like eyes, who trod her own path, playing bold female leads who were indifferent to men’s attention. As interviewer Barbara Walters said in 1987: "While other actresses concentrated on being likeable, Bette Davis set her sights on being memorable".

Courtesy of Harewood House Trust

Courtesy of Harewood House TrustThe same was true of how she handled business. In 1936, dissatisfied with the unambitious roles offered within her contract to Warner Bros, and earning a salary inferior to her contemporaries, she sued the studio. Though she lost the case, the message had been received. Not only did her pay go up, but subsequent roles such as the stubborn and spoiled Julie Marsden in Jezebel (1938), which earned her a second Oscar, and the histrionic, ageing actress Margo Channing in All About Eve (1950) made cinema history, and cemented the trope of the drama-loving diva.

"A diva," sang Beyoncé, in 2009, "is a female version of a hustler". Actor Mary Pickford knew this back in 1919. Known as "America's Sweetheart", but uncompromising when it came to her career, she broke from the stranglehold of the studio system to co-found production company United Artists, blazing a trail for numerous savvy successors, who have set up their own production companies to tell stories with strong roles for women.

Diva status depended, back then as now, on being the author of your own career – creatively and financially – and driving it forward. If this meant being labelled as difficult, it was the price performers needed to pay. Opera megastar Maria Callas (1923-1977), known for her fiery temperament, was unapologetic, stating: "I will always be as difficult as necessary to achieve the best".

Viva la diva

The diva label "has very much shifted", says Dr Kirsty Fairclough, reader in screen studies at Manchester Metropolitan University and co-editor of Diva: Feminism and Fierceness from Pop to Hip-Hop (2023), which is due for release in September. Once a way of describing a woman’s other-worldly talent, the label, she says, is increasingly applied to subdue them. "It has been used many, many times to undermine successful women, reinforcing stereotypes, diminishing their achievements and suggesting that they're difficult or temperamental," Fairclough tells BBC Culture.

Mark Sullivan/Contour/ Getty Images

Mark Sullivan/Contour/ Getty Images"What is diva behaviour?" she continues. "Maybe it's actually [just] standing up for yourself as a response to the challenges faced by female stars in industries that are male-dominated and absolutely rife with gender inequality. Asserting your power, demanding fair treatment, navigating those pressures and scrutiny, isn't it just that, rather than diva behaviour?"

Double-Grammy award winner Ariana Grande thinks so. In an interview in 2020, she said: "If I have an opinion artistically or if I'm directing something or I have something to say regarding a choice that’s being made with my career... it's always manipulated and turned into this negative thing, and I don't see that with men." She added: "I'm tired of seeing women silenced by it."

One woman who refused to be silenced was model, singer and actress Grace Jones, who famously slapped UK talk show host Russell Harty on set in 1981. Jones defended her behaviour in her 2015 memoir, stating: "I was meant to sit next to Russell Harty and keep still and quiet. I was all dressed up like an Amazonian seductress, and treated like the hired help."

Other performers point to what Fairclough describes as "the toughness born of struggle" to explain their inflexible attitude. Mariah Carey recently told The Guardian: "I deserve to be [high maintenance] at this point… after working my ass off my entire life", while in the 2021 documentary Tina, Tina Turner said: "I'm a girl from a cotton field. I pulled myself above what was not taught to me."

2022 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc / Licensed by DACS, London

2022 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc / Licensed by DACS, LondonThis narrative of struggle and survival is one that has strongly resonated with the LGBTQ+ community, who have formed an important part of the fan base of numerous divas, such as Judy Garland, Barbra Streisand and Madonna, while songs such as Gloria Gaynor's I Am What I Am (from Broadway musical La Cage aux Folles) and Lady Gaga's Born This Way have become LGBTQ+ anthems. Divas, says Fairclough, are "symbols of empowerment, self-acceptance and celebration of individuality, [and] challenging societal norms" and, as such, play an important role in LGBTQ+ culture. The diva label gets a mixed reception. On her podcast last year, Meghan Markle appeared to take umbrage at Mariah Carey calling her a diva, while Carey, the daughter of an opera singer, has come to embrace the term. "I play into it," she told W Magazine in 2022. "And yes, part of that is real." Hip-hop star Lizzo, queen of feathers, fake furs and sexy stage wear, is another artist who leans into it, while, as a plus-size woman, subverting the archetype.

Lizzo's promotion of body positivity is just one example of how dedicated divas have used their platform for good. Singer Billie Holiday, for example, turned away from her record label to speak out against civil rights with the independent release of Strange Fruit (1939), a song about black lynchings that sold in its millions despite widespread censorship; actress Elizabeth Taylor helped destigmatise HIV/Aids in the 1980s; and Beyoncé has lent her voice to the Black Lives Matter campaign.

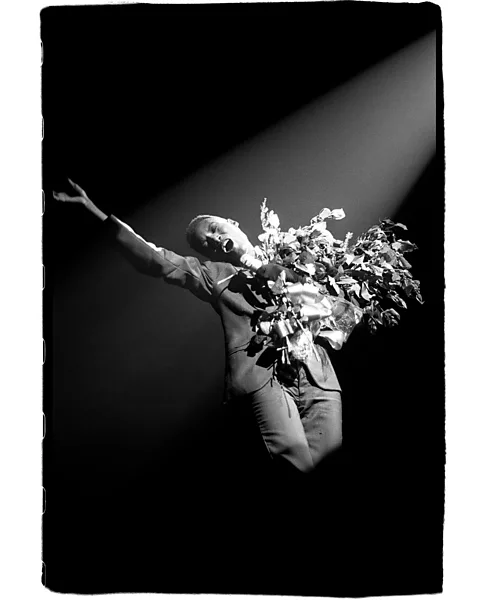

David Corio

David CorioAbove all, the V&A's DIVA will be celebratory, says curator Kate Bailey, who is keen to redress an injustice served to these extraordinary performers. "I feel that they have been misunderstood," she told BBC Culture. "If you look at the nature of the diva as an artist and how often they are looked at and scrutinised in a way which carries a lot of negativity, when actually, these solo artists are hard-working, ambitious, visionary, trail-blazing… and should be celebrated for that," she says.

Back in 1983, talk show host Johnny Carson asked 75-year-old Bette Davis how she would most like to be remembered. In matching leopard-print hat and stole, and smoking a cigarette, she looked him straight in the eye. "As a good worker," she replied. "My goal was to do the best I could."

DIVA is showing at the V&A South Kensington until 7 April 2024.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.