The American designers who were ignored

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSome of the 19th and 20th Century's most famous designs were the work of little-known names, writes Cath Pound, as a new exhibition of US and Canadian female designers – including the woman who designed the first retractable seatbelt – opens.

The fact that female artists have so frequently been overlooked is one that we are increasingly aware of. The lack of recognition of female designers, however, has had far less attention. Women had to contend with societal disapproval, workplace hostility and even institutional erasure, yet still they managed to have a major, if under-acknowledged, impact on our material culture. Parall(elles): A History of Women in Design at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts is focusing on some of the most influential US and Canadian designers in the hope of bringing their work to a wider audience.

Although women have been craft-makers for centuries, for a long time their work was considered merely decorative. That only changed thanks to the influence of the Arts and Crafts Movement at the end of the 19th Century. "The renewed attention to traditional craft-based practices meant there was a lot more attention on work that women were doing which had historically not been valued as real contributions to design," explains Mary-Dailey Desmarais, the chief curator at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts.

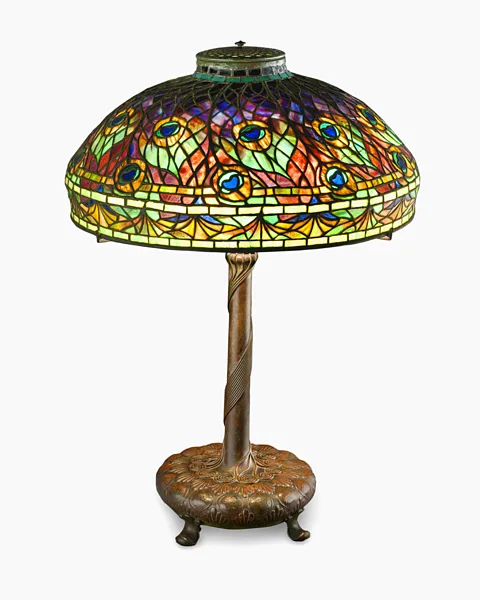

At the same time, a number of specialised design schools for women were established, providing the design education and technical training they needed in order to embark on professional careers. Clara Driscoll was one young woman who took advantage of such opportunities. Having trained at the Metropolitan Museum Art School, she was fortunate enough to get a job at the Tiffany Glass Company, which showed a rare appreciation for the skills of women. "There really was a lot of support for women from the head of the company, Louis Comfort Tiffany. Unlike many comparable firms, he actually insisted on paying women equally to men," Desmarais tells BBC Culture.

MMFA, Jean-François Brière

MMFA, Jean-François BrièreDriscoll would go on to become the head of the women's glass-cutting department, managing a team of 35 women who referred to themselves as The Tiffany Girls. She was responsible for some of Tiffany's most iconic lamp designs, including the Peacock and Wisteria, although that fact went largely unacknowledged until early this century.

"He relied on her a great deal and had enormous respect for her," Jeannine Falino, a curatorial advisor to the exhibition, tells BBC Culture. In addition to producing her designs, Tiffany "also took her for a three-month tour to Brittany to sketch with other artists. That was quite unusual for the times, and truly a measure of his respect for her talent."

Unfortunately, her male co-workers were not so supportive and deeply resented the competition from female colleagues. They threatened strike action, and although Tiffany stood by his female workers, he was eventually forced to cap the number of Driscoll's department at 27.

20th-Century pioneers

The first wave of feminism in the late 19th and early 20th Century saw a gradual softening of attitudes to women working outside the home. But it still took singularly determined women to succeed in an unrelentingly patriarchal society. Elsie de Wolfe, considered to be the US's first professional interior designer, was one such woman. Having a loathing for Victorian and Gilded Age excess, she sought to radically transform the US domestic interior through the principles of "light, air and simplicity." De Wolfe "ushered interior decorating into a new era, encouraging women to express their individuality and influencing generations of designers to come," writes curator Jennifer Laurent in the exhibition catalogue. Initially favouring a French 18th-Century style, she began to include modern French details such as animal skins after World War One.

De Wolfe was equally uncompromising, and unconventional, in her private life. "She had a lifetime companion, as the term was in those days, named Elisabeth Marbury, who herself was a pioneering theatrical agent," explains Falino. The pair were an early 20th-Century lesbian power couple, hosting celebrated Sunday afternoon teas that attracted the cream of US and European celebrities. "She pursued her own path with absolute commitment and style," says Falino admiringly.

John R Glembin

John R GlembinThe 1920s saw industrial design emerge as a profession in the US. It was, and still is, a male-dominated field – yet Belle Kogan managed to make a name for herself in that area in the middle of the Great Depression. After a decade helping out in her father's jewellery company, she was offered a job by the Quaker Silver Company, becoming one of their top designers. In 1931 she branched out on her own, opening a studio on Madison Avenue in New York and employing a small, all-female team. Kogan designed an astonishing array of products from silver hostess ware to Bakelite jewellery for companies such as Reed and Barton, Telechron and Zippo.

Despite her obvious skill, Kogan still had to endure petty misogyny. In a 1939 interview, she described travelling to a company, only for the engineers to refuse to work with her once they realised she was a woman. Kogan dismissed such slights, and continued working in the US until 1970. She then moved to Israel, having secured a contract with KV Design, and continued working into her 70s.

World War Two truly gave female designers the opportunity to prove what they could do while the men were away at war, but after the war, women faced huge pressures to return to their "traditional" roles. "Women were more than just 'encouraged' to go back to the home. Many of them were villainised. There were all kinds of studies published at the time accusing women of having penis envy, not attending to their families or being derelict in their duties to the home," says Desmarais.

However, despite these pressures, "a lot more schools were opening. There were still professional opportunities for women and professional training had been expanded," says Desmarais. Increasing consumer demand in the 1950s, coupled with an increasing awareness of the influence women could have on purchases, encouraged many companies to employ female designers in the hope of boosting sales.

When research revealed that women influenced 70% of car purchases, General Motors hired a group of female designers to work in their interior design department. Named "the Damsels of Design" by the PR department, they were put in the spotlight at General Motors Feminine Auto Show in 1958, held in a softly-lit dome fitted out with potted plants and singing canaries.

General Motors LLC

General Motors LLCRuth Glennie's Fancy Free Corvette is the only prototype to survive from the show. None were ever put into production, but Glennie's design still had a lasting impact. "She made certain things happen in car interiors that became normalised in car design – things like child-proof doors that we now take for granted, and lighted mirrors. She was also responsible for designing the first retractable seatbelts. She did leave a legacy that we enjoy today," says Falino.

There were few female designers working in mainstream modernist design, but some did become known, thanks to their inclusion in MoMA's Good Design Programme, a series of semi-annual awards and exhibitions. Certain works shown in the exhibitions have since become modernist icons, such as Greta Magnusson's Cobra lamp and Greta von Nessen's Anywhere lamp.

However, the museum was also responsible for some horrendous omissions. Ray and Charles Eames are without doubt one of the greatest design teams of the 20th Century and are responsible for some truly iconic designs. Yet when Eliot Noyes, head of MoMA's industrial design department, invited them to show their furniture in 1946, it was billed as the museum's first "one-man" furniture exhibition and titled New Furniture by Charles Eames. Noyes rubbed salt in the wound in an article for Art and Architecture, writing that: "Charles Eames has designed and produced the most important group of furniture ever produced in this country." Ray was only mentioned as his wife and 'helper'.

![MMFA, Christine Guest LCW [Low-Chair-Wood] chair, 1945-1946, designed by Charles and Ray Eames and produced by Herman Miller Furniture, Zeeland, Michigan (Credit: MMFA, Christine Guest)](https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/images/ic/480xn/p0f9f49v.jpg.webp) MMFA, Christine Guest

MMFA, Christine Guest"Charles himself really did say that it was an equal partnership and alliance," says Desmarais. And one would like to think Ray's involvement is now fully recognised, but as late as 2006 The New York Times Magazine was referring to the couple as "The Eames brothers".

The 1960s and 70s saw second-wave feminists embrace pattern and decoration as a feminist strategy. This included Wendy Maruyama, one of the first women to enrol in a Master of Fine Arts Furniture Making Programme in the US. Maruyama, known for her innovative wooden furniture, has said of her early work that it was "about being empowered in what is traditionally a male-dominated field".

"She introduced colour when furniture makers were still in this 'reverence for wood' period," says Falino. "The guys were all about the wood and the grain, and she challenged that. She also inserted a kind of jauntiness and attitude into her process. Her work has a great physicality, a more sculptural presence. She achieved what the guys couldn't. They were following the herd and she refused to do that."

Maruyama, now in her 70s, is still going strong. "Her work more recently has engaged with broader issues relating to the environment and the treatment of animals. She's certainly someone who has a very strong engagement through her practice," says Desmarais.

Let's hope that exhibitions such as Parall(elles) will bring greater recognition to all these phenomenal women. But Desmarais notes that although more attention has been given to designers such as Driscoll in recent years, "much more work remains to be done to bring the achievements of these women to light."

And Falino says there is still work to be done around the position of contemporary female designers. Although many are now reaching the tops of their professions, "we all know, women are still not being paid the same as men. There is still a resentment you can find if you're trying to make your way in a field like architecture which has a preponderance of men," she says.

"In 125 years, if you think of the span of the show, we've come a long way. But do we have further to go? Absolutely."

Parall(elles): A History of Women in Design is at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts until 28 May 2023.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.