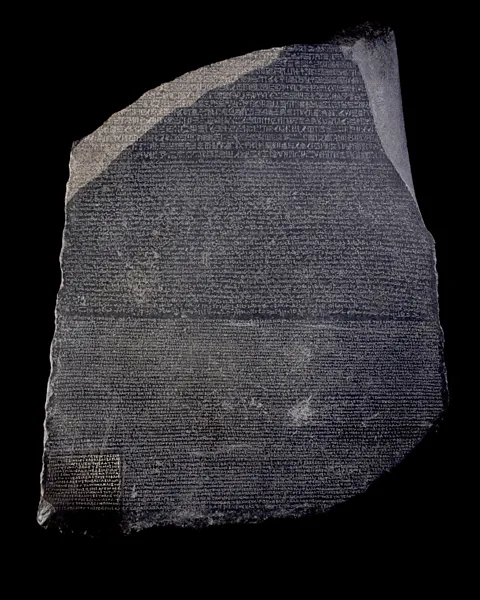

The Rosetta Stone: The real ancient codebreakers

British Museum

British MuseumEgyptian hieroglyphs were fully unlocked 200 years ago, when the Rosetta Stone was deciphered. Yet long before that, Arabic scholars had made their own discoveries with these ancient scripts, writes Daisy Dunn in the first of BBC Culture's new series Secret Languages.

Jean-François Champollion had been struggling over the hieroglyphs on the Rosetta Stone for years when, one September afternoon in 1822, he believed he had finally cracked it. In his intense excitement, the 31-year-old Frenchman gathered up his notes, hurried to find his brother, and promptly fainted.

The chance discovery of the monument in the Nile Delta at Rosetta, modern Rashid, some 23 years earlier had roused the interest of scholars globally. One of Napoleon's lieutenants, a military engineer named Pierre-François-Xavier Bouchard, was directing the demolition and reconstruction of the city's fort in July 1799 when the black object was spotted beneath the debris. To his credit, Bouchard realised at once that it was something important, and had it cleaned before taking it to the respected Institut d'Égypte in Cairo for closer examination.

More like this:

- The ancient Islamic roots of modernity

Strikingly, the heavy slab featured three inscriptions, each of which was very different to look at. One was written in classical Greek; another in Egyptian hieroglyphs; and the third in what was assumed to be Syriac, but later identified as Demotic (a later Egyptian script used for day-to-day correspondence). As Bouchard perceived, assuming the inscriptions all said the same thing, knowledge of Greek could be used to decode the other two texts, which had until now eluded total decipherment.

This prospect was immensely exciting. The stone was therefore shipped to the Society of Antiquaries in London where copies were made and disseminated to cities and universities across the world. The original was installed at the British Museum at the bequest of King George III in 1802.

The race was then on to translate the Greek and use it to unravel the secrets of the other two languages. The legible text confirmed that the three inscriptions were indeed identical in content and related to a decree passed by a council of priests in Memphis regarding the cult of Ptolemy V in the 2nd Century BC. As the timeframe between the excavation of the stone in 1799 and Champollion's eureka moment in 1822 suggests, however, the code-cracking challenge proved harder than anticipated. What was more, contrary to his belief, Champollion had solved only part of the puzzle when he leapt from his chair claiming to have "Got it!"

British Museum

British MuseumIn October, an exhibition will open at the British Museum in London to mark the bicentenary of Champollion's breakthrough, which anticipated his complete decipherment of hieroglyphs. As the accompanying catalogue explains, the Figeac-born scholar "was certainly the first to grasp the structural logic of the ancient Egyptian language in its varied forms", and consequently enjoyed an enduring reputation as the man who won the intellectual race. But was Champollion really the trailblazer he was believed to be?

Almost a millennium before the Rosetta Stone was even discovered, Arabic scholars had begun to grapple with the hieroglyphs they found on Egyptian monuments and tomb paintings. The highly pictorial method of writing was first developed about 3250 BC and known in Egyptian as "divine words" and in Greek as "sacred carving" or "hieroglyph". Although it had ceased to be used by the 5th Century AD, these medieval scholars believed that the script could still be deciphered, and the secrets of the inscriptions revealed.

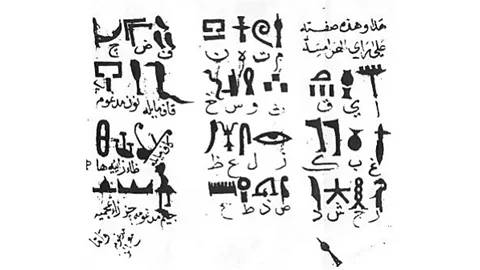

In the 9th Century, an Iraqi alchemist named Abu Bakr Ahmad Ibn Wahshiyya turned his hand to translating hieroglyphs in the hope of rediscovering lost scientific knowledge. This belief, says Dr Okasha El Daly, senior honorary research fellow at the Institute of Archaeology at University College London and head of acquisitions at Qatar University Press, "wasn't that far-fetched, for some temple walls do have scientific texts relating to alchemic processes on them".

Ibn Al-Nadim, the son of a 10th-Century Baghdadi bookseller, recorded seeing Ibn Wahshiyya's notebooks full of symbols. Not only was Ibn Wahshiyya able to understand some of the hieroglyphs, but, as Al-Nadim pointed out, he was apparently working with the concept – later employed by Champollion – that a known script could be used to decipher an as-yet unknown one.

Alamy

AlamyThis method was almost simultaneously taken up by Champollion's chief rival Thomas Young. Described by his modern biographer as the "The Last Man Who Knew Everything", the English polymath concentrated on the Demotic script on the stone, realising that this could provide the key to understanding the hieroglyphs. In a book of 1814, Young revealed some of his workings across the three inscriptions of the Rosetta Stone. His eventual success in deciphering Demotic proved invaluable to Champollion, who proceeded to beat him in the contest to decode the corresponding hieroglyphs.

Accumulated wisdom

As Dr El Daly tells BBC Culture, "Scientific progress is an accumulated thing. Champollion did not work from nothing. He started from studying earlier contributions. He also knew Arabic." It is highly likely, indeed, that the linguist accessed manuscripts containing some of the work by Arabic writers who had attempted to decipher hieroglyphs in the intervening millennium.

An earlier Western scholar, Athanasius Kircher of Germany, had certainly done precisely this and consulted Arabic writings, usually in translation, while carrying out research for his own book on deciphering Egyptian hieroglyphs. More than 40 Arabic sources are mentioned in Kircher's sprawling Oedipus Aegyptiacusof the mid-17th Century. His knowledge of the work of Ibn Wahshiyah is not in doubt. Unfortunately, Champollion failed to cite his sources in the same way, meaning that the contribution of earlier scholars to his eventual success has been difficult to assess in any depth.

Alamy

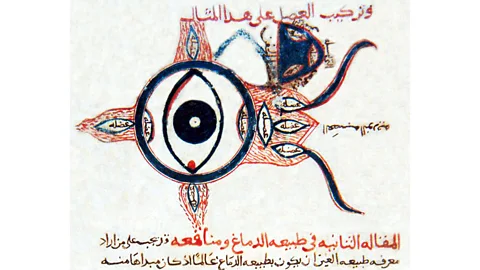

AlamyIt was not unusual for the transmission of knowledge to be clouded in this way as it travelled through the hands of scribes and scholars in the East. Dr Violet Moller, author of The Map of Knowledge, explains that Arabic scholars who were instrumental in carrying ideas from antiquity into the Renaissance have all too often been overlooked or even written out of history. "It's impossible to know what the individual motives behind this were. When the medical books of the Greek author Galen, for example, were translated from Greek into Arabic, revised and significantly amended by a man named Hunayn Ibn Ishaq, some Latin scholars presented the work as purely Greek. There was no mention of the Arabic scholar who was the conduit of knowledge," she says.

According to Moller, "There was more broadly a belief that the Greeks had a higher kind of knowledge. There was also certainly an element of anti-Islamic sentiment, the result of antagonism between Arabs and Christians in the period. But there was an Arab scholar from North Africa who translated a text into Latin in Italy and he did the same thing [in obscuring the non-Western contribution]. It was probably partly pragmatic: texts based on Greek knowledge would be more attractive to European scholars."

It is possible, though perhaps unlikely, that Champollion would have gone on to credit his sources at a later date. As Dr Daly notes, he died just 10 years after his breakthrough with the decipherment, and might have been tempted to revisit his publications. If he had, in addition to Ibn Wahshiyah, his bibliography might have named Athanasius Kircher. The German had provided other Western scholars with an important way in to the earlier Arabic scholarship. Kircher had also made it clear that mastering Coptic was key to mastering hieroglyphs.

Coptic was a late Egyptian script that combined 24 Greek letters with seven Egyptian Demotic letters and was often used in academic contexts. A 13th-Century Egyptian scholar called al-Idrisi was among those to have drawn an early connection between this script and hieroglyphs. Several Arabic manuscripts from the same period as al-Idrisi was working indeed feature Coptic grammar guides and a number of these were introduced to the West. Kircher probed the connection between the two scripts further by mapping certain hieroglyphic symbols on to Coptic letters. In the process he confirmed the earlier Arabic scholars' hypothesis that some hieroglyphs had phonetic meanings.

Champollion, following a similar path, initially downplayed the phonetic element of the script. His first thought was that hieroglyphs represented sounds predominantly when they were employed to write non-Egyptian names. Later, after his fainting episode, he realised that phonetics were in fact a central component of the script and could be used to denote Egyptian names too. A single sound, he showed, could be represented by more than one hieroglyph. This was not just a script, he realised, but a spoken language.

There is no denying that Champollion made an enormous contribution to the history of scholarship in making these discoveries. "Without Champollion," says Dr El Daly, "our knowledge would have had to wait a few more decades." His decipherment of the hieroglyphs on the Rosetta Stone facilitated the translation of hundreds of other previously incomprehensible texts down the centuries and therefore opened up countless new avenues of scholarship and debate. On a human level, too, Champollion clearly deserved the praise he received for his perseverance and intellectual clout.

But as we celebrate Champollion's grand achievement 200 years on, might we not also think of the other scholars who, though in many cases obscure today, through their own discoveries helped him on his way? It is arguable that the likes of Ibn Wahshiyah, Athanasius Kircher and Thomas Young worked no less tirelessly to unpick the mysteries of the most mysterious of ancient scripts. Now is the time to put them back into the puzzle they embarked upon so zealously all those centuries ago.

Daisy Dunn is the author of In the Shadow of Vesuvius: A Life of Pliny.

Hieroglyphs: Unlocking Ancient Egypt is at the British Museum from 13 October to 19 February.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.