Orlando: The most subversive history film ever made

Alamy

AlamySally Potter's adaptation of Virginia Woolf's classic novel – the film marking its 30th anniversary this year – starred Tilda Swinton as a time-travelling, sex-changing figure. It was a transgressive riposte to the homophobia of early-90s Britain, and remains relevant today, writes Rachel Pronger.

Orlando is a book that inspires devotion. Virginia Woolf's experimental novel was an immediate critical and commercial success when it was first published in 1928, and its reputation has only grown since. The story of a time-travelling aristocrat who lives through 400 years of history – and changes sex along the way – Orlando was originally written as a tribute to Woolf's lover Vita Sackville-West, and is now celebrated as a queer and feminist landmark. It has inspired generations of artists, filmmakers and writers, and been reimagined as ballet, opera and theatre – the latest stage version opens in London this autumn.

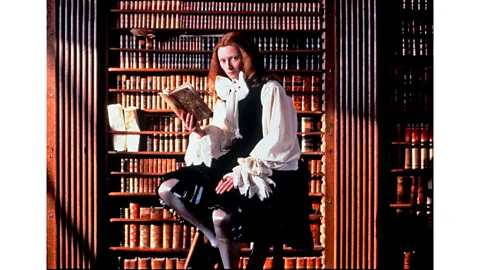

The best of these retellings approach Orlando as an ever-evolving work of queer imagination. Sally Potter's film adaptation, which marks its 30th anniversary this year, is a case in point. Warmly received upon its Venice Film Festival premiere in 1992, Potter's Orlando is now considered a bravura work of adaptation. Starring Tilda Swinton in the title role, the film is a historical romp full of wit and sumptuous detail. Yet despite the era-spanning narrative, it's also a film that reflects a very specific moment in British history. True to the spirit of Woolf's text, Potter's Orlando is steeped in queer culture, and has become over the decades a subject of fascination – and ambivalence – for successive generations of LGBTQI+ fans.

It took Potter almost a decade to bring Orlando to the screen. The filmmaker first fell in love with the book as a teenager, immediately recognising its cinematic potential. "When I read it, I could see it," Potter has said. "I experienced it… as a series of images hurtling through time and space from 1600 to the present day." She began pitching Orlando to funders in 1984, but was told that the concept was "unmakeable, impossible, far too expensive and anyway not interesting." Potter was temporarily discouraged, but in the late-1980s she returned to the project with renewed determination.

Alamy

AlamyAdapting Woolf's amorphous text was a challenge. In a 1993 interview, Potter described how she initially worked methodically – "reading, re-reading and reading again" – before putting the novel aside, and treating the script "as something in its own right, as if the book never existed." The resulting screenplay captures Woolf's anarchic spirit but makes bold adjustments to facilitate the translation to a new art form. The book's addresses to the reader for instance, are reflected by Orlando's playful breaking of the fourth wall. In one memorable scene, Orlando wakes from a long sleep to discover they are now in a woman's body. "Same person, no difference at all," says a naked Swinton, looking directly down the camera lens. "Just a different sex."

Potter also made significant plot changes. Woolf does not explain Orlando's immortality, but in the film it is implied that this longevity has been gifted by Queen Elizabeth (Quentin Crisp) who, infatuated by Orlando's beauty, insists they must stay young: "do not fade, do not wither, do not grow old." Potter also offers a bittersweet change to the ending by having the protagonist give birth to a daughter rather than a son, resulting in the loss of Orlando's inheritance. This change reflects more accurately the real life of Sackville-West, who as a woman was barred from inheriting her ancestral home of Knole. These adjustments serve to draw out the novel's queer and feminist subtext, and in doing so they also suggest ways in which the film was shaped by the era in which it was made.

'A contradictory moment'

Potter began making films in the 1980s as part of a radical artistic scene working in response to the neoconservatism of Margaret Thatcher's Britain. Section 28, which prohibited the "promotion of homosexuality" by local authorities, was introduced in 1988, against the backdrop of the escalating Aids crisis. Filmmakers such as Derek Jarman reacted to this heightened homophobia by making outspoken work centring queer politics, boundary-pushing films that found a home on television on the newly launched Channel 4.

As the writer So Mayer explains, this was a contradictory moment. "What's happening in the early 1990s is the crest of a wave that starts in the squats and protests of the 1970s," Mayer tells BBC Culture. "Queer experimental art was being made in the face of institutionalised and culturally prevalent homophobia. Orlando's conceptualisation starts in the heart of neoliberalism and Thatcherite destruction." With its luscious historical imagery, Potter's film might look like an escapist fantasy, but it is littered with topical references to this very specific socio-political moment.

Although it does not offer explicit political critique, Orlando radically centres queer culture, and is full of references that speak to LGBTQI+ viewers across the generations. By casting an 83-year-old Quentin Crisp as Queen Elizabeth I, Potter pays tribute to a gay icon while adding another layer to the film's discussion of identity. Described by Potter as "the Queen of Queens," Crisp would go on to identify as transgender and use she/her pronouns in the final years of her life. Rewatching the film with this knowledge adds a dimension to the film's reflections on the mutability of gender.

Elsewhere, a recurring cameo from musician and activist Jimmy Somerville gestures towards a younger generation. Somerville first appears as a Tudor countertenor in the film's opening scenes before popping up again across each of the film's eras. A final surreal appearance at the film's conclusion – in which Somerville stars as a tinfoil-clad angel singing in the sky – seems to reference the Aids crisis, which at that moment was having a devastating effect on the queer artistic community within which Potter was working.

One high-profile victim was Derek Jarman, who would die of Aids-related illnesses in 1994. Although not directly involved in Orlando, Jarman was an important influence. Potter and Jarman had first become friends in the mid-1980s when visiting the then-Soviet Union as part of a delegation of independent filmmakers. "As the only gay male and the only female directors in the group we became natural allies," Potter remembered. Jarman publicly advocated for Potter as she struggled to get Orlando made, and the film is indebted to Jarman's iconoclastic approach to period drama, as seen in Caravaggio (1986) and Edward II (1991). Potter also recruited several Jarman collaborators, most notably Swinton, and the costume designer Sandy Powell. In Orlando, Potter draws upon Jarman's pioneering "queering" of the historical genre, and in doing so furthers a legacy that has been continued in recent subversive period pieces such as The Favourite.

An enduring message

Given these ties to queer culture, it's unsurprising that Orlando often provokes strong reactions in LGBTQI+ viewers. Mayer has written a book on Potter and is currently working on a monograph about Orlando. They remember vividly the first time that they saw the film as teenagers in 1993. "My friends hated it, and wanted to leave; I was enrapt and wouldn't," recalls Mayer. "So my first memory of watching the film is having a furious row in whispers with my then-best friends, who walked off after the screening." Years later, Mayer realised that part of the film's appeal was its queerness. "It had given me a window into something that I had only glimpsed through [long-running BBC pop music programme] Top of the Pops… In some ways, I understood that I loved it for the same reasons that my friends hated it, and that they were reasons, both aesthetic and political, that I couldn't articulate."

Alamy

AlamyOrlando's unpindownable quality has often provoked debate. Greater awareness of Woolf's queerness has added to this discussion, as has our evolving understanding of gender identity. Is Orlando, as Jeanette Winterson has argued, "the first English-language trans novel?" Does Potter's film centre trans-femininity, or is it about non-binary identity or gender fluidity? Even Swinton has joined in, arguing in a 2020 interview with Sight and Sound that Orlando is not about gender but rather "sheer boundarylessness and endless evolution… my thesis is that if Woolf had written another thousand words, a thousand pages, Orlando could have easily turned into a spaniel next or a fly or a bottle of wine or anything else."

Artist Liz Rosenfeld jokes that they've seen the film "a 1000 times". "It's one of those I know like the back of my hand, like Dirty Dancing," says Rosenfeld, who has often screened it to students. "I could do a one-person show of Orlando." But Rosenfeld also has reservations about some of Potter's choices. "I always wished that Jarman had made Orlando, even though I love Potter," they say. "For me the problem is that it reads like a lot of Virginia Woolf (even though I'm a huge Woolf fan), like neoliberal white feminism."

Alamy

AlamyFor Rosenfeld, part of the issue lies in the film's casting. "I think the reason why the movie functions is because we're never seeing Orlando, we're seeing Tilda Swinton the whole time." Although quick to point out that Swinton is brilliant, Rosenfeld suggests that the choice of a slim, white, aristocratic actor reinforces a narrow reading of acceptable androgyny. "She's such a blank palette, for so many people she can be so many things. The problem is that every kind of trans person should be able to feel that they can safely shift, and the reality is that we can't... As a fat, trans non-binary person, I've always been readable as a queer body, I've never felt like a chameleon in the way that Orlando has the privilege of." Rosenfeld doesn't read Orlando as a trans film. "Everyone hails it as a trans masterpiece, but I really don't see it as a trans story actually," they say. "I see it as a time-travelling story because it's about the potential of bodies moving through space and time differently, without explanation. In this respect, it is a queer story."

Mayer does see Orlando as a trans text, although they highlight how interpretations of the film are inevitably shaped by personal experience. "Different viewers see it differently… I do believe that the protagonist is trans," says Mayer. "That is meaningful to me both as representation, and because it is also a metaphysical and formal meditation on and engagement with gender as being in time." Nevertheless, Mayer embraces the multitude of readings presented by the film, reminding us that to read the film through one lens does not necessarily mean cutting off all other possibilities. "I think it is a trans text and a gender-fluid text, a queer text and, importantly, a feminist text."

![Alamy Virginia Woolf wrote Orlando as a tribute to her lover, Vita Sackville-West [right] (Credit: Alamy)](https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/images/ic/480xn/p0d048wy.jpg.webp) Alamy

AlamyDespite their affection for both the book and the film, Rosenfeld suggests that Orlando's status as the definitive trans or gender-fluid text should be questioned. "I know there have been a lot of restagings of Orlando, but I sometimes wonder if this is something that is worth reinterpreting and rethinking," says Rosenfeld. "I'm not sure actually, because there are so many incredible current-day trans narratives that it's almost like [Orlando] is history somehow."

As Rosenfeld's comments suggest, Orlando is, like all of us, a product of a specific moment. However, one thing that Woolf's enduring tale expresses is that time sometimes does not move how we expect it to. Perhaps one of the reasons why the film endures is because history repeats itself. Revisiting Potter's Orlando now, in an era of culture wars and resurgent anti-trans rhetoric, it's striking how revelatory it feels to watch a film that treats gender identity with such lightness.

For Mayer, this playfulness is key to the film's power. "It did not tragicise or sermonise," they say. "It showed and shared… the possibility of euphoria, of queer joy." The way that Orlando moves joyfully forward despite the obstacles placed in their way, offers a hopeful vision of queerness that remains unusual. Regardless of how you interpret their identity, there is quite simply no other character, in literature or cinema, quite like Orlando.

Love film and TV? Join BBC Culture Film and TV Club on Facebook, a community for cinephiles all over the world.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.