The ancient Islamic roots of modernity

Keir Collection of Islamic Art/ Dallas Museum of Art

Keir Collection of Islamic Art/ Dallas Museum of ArtThere was a particular moment in history when no artistic field was immune to the influence of Islamic design, writes Cath Pound.

Cartier and Islamic Art: In Search of Modernity, currently on show at the Dallas Museum of Art after a hugely successful run at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris, reveals the way in which the geometric designs of Islamic art provided Cartier with the inspiration to create a ground-breaking modern aesthetic for fine jewellery at the very beginning of the 20th Century.

More like this:

Cartier's designs are part of a centuries-long relationship between European artistic creation and Islamic art. It is a relationship that Olivier Gabet, director of the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, acknowledges in the catalogue has always been "highly political", with its "mix of fascination, violence and domination".

Cartier

CartierAlthough for centuries traders and diplomats had been the only Europeans able to visit the empires of the Middle East, the advent of the colonial era and the increasing Western influence in the region saw opportunities for travel opening up in the 19th Century. A stream of North American and European artists flocked to Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul), Jerusalem, Cairo and Marrakech. The paintings they created freely merged fantasy with reality, especially when it came to depictions of the harem, to which no male would have ever been granted access, which depicted local women with an exoticised otherness that also reflected a sense of Western superiority.

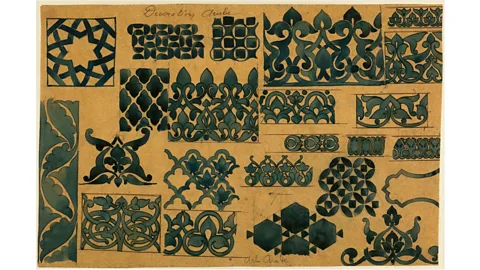

But although the clichéd Orientalism of these works has been criticised, the paintings provided wider audiences with their first glimpse of the beauty of Islamic craftsmanship, an area which was then of little interest to Western museums and scholars. The scenes these artists portrayed may have been inaccurate, but the objects and artefacts they depicted were rendered with unstinting accuracy. The stylised floral tile designs, geometric architectural features, ornate metalwork, spectacular jewellery and intricately woven textiles and rugs left Western collectors spellbound.

Lucien de Guise curated Beyond Orientalism, a 2008 exhibition at the Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia exploring Islamic art's influence on the West. He tells BBC Culture "the paintings came before the scholarship. A lot of people are buying things because they're popular and in demand, and the reason they're popular and in demand is because the artists a generation before had been to these places and brought back huge quantities of carpets and weapons and other artefacts."

Keir Collection, on loan to Dallas Museum of Art

Keir Collection, on loan to Dallas Museum of ArtWhile collectors were enthusiastically buying originals, designers were using them for inspiration. Ottoman ceramics influenced everyone from William de Morgan to Villeray and Bosch, while the delicate Alhambra vases inspired lusterware imitations from makers such as the Hungarian porcelain and glassware maker Zsolnay. For the aesthetically-aware bourgeoisie, books such as Christopher Dresser's Studies in Design (1876) offered tips on how to use Islamic motifs in the home.

Tragically, just as the West was waking up to the beauty and skill of Islamic decorative arts, the practice of those crafts was under threat in their native countries. The combination of Western colonisation and economic and cultural infiltration into unoccupied lands led to "a period of artistic lethargy and cultural stagnation", the Jordanian art historian Wijdan Ali declared in a 1992 article entitled The Status of Islamic Art in the Twentieth Century. Soon "Western aesthetics overpowered indigenous artistic traditions," she wrote.

"They were losing their power and becoming more Westernised. They were desperate to modernise, and were not giving the attention to their own generations of craftsmen that they would have done until the 19th Century," says de Guise.

But while appreciation of Islamic arts was increasing in the West, it was still tainted with clichéd interpretations. In 1864 a new institution, the Union Centrale des Beaux-Arts Appliqués à l'Industrie, was created by a group of enthusiasts dedicated to the study of Islamic art. Renamed the Union Centrale des Arts Décoratifs in 1882, they were instrumental in the first exhibition of "Muslim" art at the Palais de l'Industrie in 1893. The quality of items on display was incredible, and it clearly had serious intentions to trace the history of Eastern art and even stimulate Western creativity. However the Orientalist scenography and mixing of genres was not appreciated by increasingly well-informed, serious collectors.

Keir Collection/ Dallas Museum of Art

Keir Collection/ Dallas Museum of ArtIt wasn't until 1903 that the first truly scientific display was organised by a young curator from the Louvre, Gaston Migeon. His Exposition des arts Musulmans was met with unprecedented enthusiasm. "One's eyes were not truly opened until 1903," wrote the art collector Georges Marteau.

Visual vocabulary

Although it is not known for certain if Louis Cartier, the eldest Cartier brother who would be instrumental in expanding the firm's global reputation, visited the exhibition, a catalogue exists in the Cartier archives, so it is clear he would have been aware of its contents. At the time, jewellers were stuck in a rut of endlessly recycling historic European styles. Sarah Schleuning, curator of decorative arts and design at the Dallas Museum of Art, tells BBC Culture: "If you look at Cartier themselves, they were really in that neoclassical, what we now call the garland, style… there's a kind of heaviness and an ornateness."

Cartier was "interested in finding a new style but he wasn't interested in the modern aesthetic of the time which was the transition to Art Nouveau," says Schleuning. The 1903 exhibition gave him the visual vocabulary he was looking for. "He saw the geometry, these distilled motifs, as an incredible path forward, and you start to see them as early as 1903. He's starting to play with them, sometimes in pure isolation like in this incredible, very minimalist, little brooch that is just a series of triangles. But in other cases, you see it infiltrating with these kind of garland styles, so they're starting to insert and play with that and think, how do you transition," says Schleuning.

The 1903 Paris show was followed by an equally ground-breaking exhibition in Munich in 1910 that carefully grouped objects according to technique and geographical origin with the specific intention of inspiring contemporary creativity. This exhibition is thought to have been the catalyst for Louis Cartier to develop his own collection. He had a particular taste for manuscripts, paintings and inlaid objects from Iran and India from the 16th and 17th Centuries.

Nils Hermann, Collection Cartier

Nils Hermann, Collection CartierFrom that point on, Islamic architecture, manuscripts and textiles would become an increasingly notable source of inspiration for Cartier's designers. The crenelated parapets known as merlons, brick patterns, almond-shaped mandorlas, finials and scrolls all became characteristic Cartier motifs. From the 1910s the materials and colours of the Iranian world would be particularly influential, with the blue of lapis lazuli or sapphire and green of jade or emeralds appearing in the famous peacock pattern. Elsewhere Iranian turquoise was combined with deep-blue speckled Afghanistan lapis lazuli in order to reproduce the colour combinations often found in the glazed ceramic brickwork and tiles of Central Asia.

Coral and black was another favoured colour combination which can be seen in one of Schleuning's favourite pieces, a 1922 bandeau made of coral, onyx and diamonds. "It's one of those pieces that has it all," she says. "You see them playing with these colonnades and horseshoe arches but it's distilled in miniature and wrapped in a curvilinear form so you're wearing this mini architecture."

Although Cartier undoubtedly made uniquely innovative use of Islamic motifs, creating a stunningly modern aesthetic in the process, there was no artistic field that remained immune to the influence of Islamic design.

Nils Harmann, Collection Cartier

Nils Harmann, Collection CartierLike Louis Cartier, Henri Matisse had visited the 1910 Munich exhibition. Afterwards he made a pilgrimage to southern Spain where he visited the Alhambra, the palace and fortress complex of the Moorish monarchs of Granada, famed for its exquisite decoration. De Guise notes that after this visit, Matisse's colour became more intense, his pattern flatter, and when creating his pioneering paper cut-outs, "the similarities with the tessellated tile work that he had seen at the Alhambra became unmistakable". MC Escher was equally fascinated by the Alhambra. Its symmetry and mathematical ingenuity would inspire his mind-boggling visual works.

In the performing arts, Leon Bakst's Oriental costumes for the Ballets Russes caused a sensation, influencing the Couturier Paul Poiret who turned his passion for the Orient into a virtual lifestyle experience which incorporated fashion, furniture and textiles. Carlo Bugatti, one of the most innovative furniture designers of the late 19th and early 20th Century, would also use Islamic design effects, such as muqarnas and horseshoe arches, in his designs.

Of course, stylistic influences wax and wane, and by the mid-20th Century, Islamic design had fallen out of favour in the West. However, a number of recent exhibitions have explored the influence of Islamic Art on the West, including Islamophiles: L'Europe moderne et les arts d'Islam at the Musée des Beaux Arts in Lyons in 2011, and Inspired by the East: How the Islamic World Influenced Western Art, which was on view at the British Museum in 2019, and was due to travel to the Islamic Museum of Art, Malaysia, before the pandemic intervened.

Nils Harmann, Collection Cartier

Nils Harmann, Collection CartierWith this increasing awareness and interest, Schleuning wonders if the Cartier exhibition could act as a catalyst for a new generation of artists and designers. "We're showing objects that were shown in the 1903 exhibition, and we're also showing a trajectory of how they inspired an individual. But at the same time, we're presenting that same body of objects to a new audience and the curiosity for us is what's going to come out of these pieces being shown again," she says.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.