Cornelia Parker: The artist who likes to blow things up

Cornelia Parker

Cornelia ParkerCornelia Parker uses explosives, steamrollers and snake venom in her work – as a major exhibition opens in London, Kelly Grovier explores what's behind the artist's "violent transformations".

When the British artist Cornelia Parker was a little girl, one of three daughters of a physically abusive father on a smallholding in Cheshire in the 1960s, she used to place coins on nearby railway tracks to watch them violently transformed – crushed from mundane usefulness into something mangled and more precious: works of art. For a child forced to swap playtime for mucking out stables and milking cows, the seemingly innocuous act was exhilaratingly destructive. By exploiting the menacing power of a passing train in order to stamp fresh values on to ordinary objects, Parker did not simply squash a penny. She minted an imagination.

More like this:

Since the late 1980s, Parker has produced some of the most arresting works in contemporary art by harnessing – as outrageous agents of creative change – everything from plastic explosives to steamrollers, snake venom to the very blade of the guillotine that lopped off the head of Marie Antoinette. For the first major survey of her work ever staged in London, Tate Britain has assembled nearly 100 of Parker's sculptures, installations, drawings, films and photographs, chronicling more than three decades of her determination to wring from the bruised, broken and battered fragments of life an indestructible beauty. It's all here: from small drawings made by sewing through paper a fine wire fashioned from melted bullets, to the explosive large-scale works that shot Parker to prominence 30 years ago, including the suspended remnants of a garden shed that she persuaded the British Army to help her blow to smithereens in 1991.

Cornelia Parker/Tate Photography

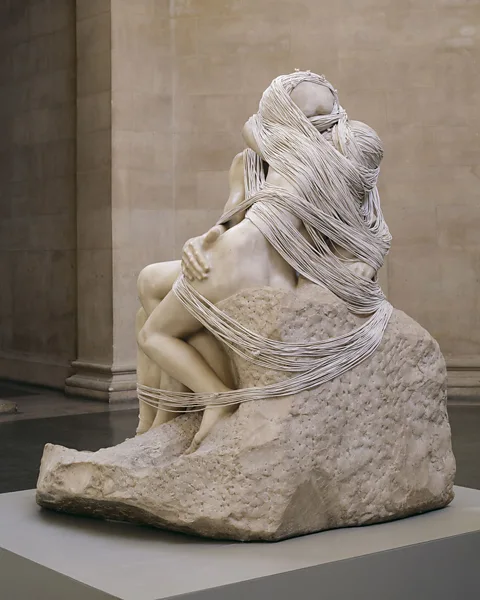

Cornelia Parker/Tate Photography"Everything just sort of weaves together," Parker tells BBC Culture, reflecting on the sight of so much of her life's creative effort gathered in one place. "The Tate owns all my major works, so they just had to get them out of the old archive. I've got a piece where I wrap Rodin's The Kiss up in string. They own The Kiss, and they'll allow me to re-enact my work." Re-enactment is a crucial aspect of Parker's imagination and art, which often ropes our eyes into seeing familiar objects as if for the first time. In 2003 she intervened in French sculptor Auguste Rodin's iconic marble depiction of adulterous lovers from Dante's Inferno – among the Tate's many treasures – by wrapping the famous marble canoodle in a mile of string, and wryly rechristening it The Distance (A Kiss with String Attached).

Through fresh eyes

As with all of Parker's work, there is something much more at play than meets the eye in her ephemeral defacement of Rodin's masterpiece. Her carefully calibrated choice of a "mile of string" is an allusion to a famous prank played by the pioneering French avant-garde artist Marcel Duchamp, who in 1942 used the same length of string to web the inside of a museum displaying works by his fellow surrealists, making it extremely awkward to walk around and see the show. But Parker isn't merely rehearsing an impish prank that made engaging with works almost impossible. By cocooning the cold and chiselled clinch of Dante's lovers, Paolo Malatesta and Francesca da Rimini, Parker reinvents Rodin's sculpture. Simultaneously obscuring and accentuating the contours of Rodin's work, the alternating slackness and tautness of the spooling string forces our eyes to unravel the profundity of a cultural touchstone that we have looked at so many times we no longer really see it.

Like Marcel Duchamp before her, who notoriously tipped an unused urinal on its side in 1917, signed the ceramic with the nom de plume "R. Mutt", and dared us to accept it as a sculpture, Parker is a relentless resurrector of found objects. But there's a difference. A big one. Where Duchamp's seminal notion of the "readymade" depends on minimal intercession by the artist, Parker's art invariably manifests the effects of extreme and strenuous disruption. Far from purely conceptual, her work is devastatingly physical – a physicality she leverages through formidable force into something more deeply psychological and emotional. In that sense, Parker's approach is far more traditional than it might at first seem.

The story of art is, after all, the story of destruction – of pummelling things into unexpected expressiveness. Were it not for the crushing of countless crimson cochineal beetles and the violent wrenching of purple mucus glands from millions of living sea snails, the rich reds and vivid violets that vibrate from some of the most memorable paintings in art history, from Rubens to Rembrandt, would be dimmed to dullness. From its very inception, art is wreckage resurrected. We know now that the earliest Stone Age artists incinerated shattered animal skeletons and pulverised the carbonised fragments to produce a radiant black pigment that they used to sketch the static stampede of bison on cave walls. A quick flip through the influential Il libro dell'arte (or The Book of Art") – a handbook written at the turn of the 15th Century by the Italian painter Cennino Cennini – and one's eyes are hammered by more than 200 references to the "crushing", "boiling", "grinding", "pounding", "beating", and "squeezing" of ingredients necessary to make art – to magick beauty from a blizzard of brokenness. Ruination and imagination more than merely rhyme; they go hand in hand when hands make art.

Cornelia Parker

Cornelia ParkerParker's instinct to squeeze startling music from familiar things is evident in the earliest work on show, her breakout installation Thirty Pieces of Silver (1988-89), which she made in her early 30s by driving a steamroller over more than 1,000 silver and silver-plated objects. The flattened teapots and trombones, baby spoons and cigarette cases had been gathered from car boot sales, markets, and the second-hand stall that she helped run at Portobello market in London. Freed from their former shapes and utilitarian functions, the rumpled tableware, trophies and instruments were divided into 30 separate pools, or "discs", of polished rubble that Parker then dangled poetically from long wires a few inches from the floor.

The floating wreckage is at once rough and irregular in its dishevelled design, and carefully measured and mathematical, forming a minimalist grid that is five rows wide and six rows long – a precision that connects her work to the soulful meditations of geometric abstractionists like Piet Mondrian and Agnes Martin. "In the gallery," Parker explained at the time the work was first exhibited at the Hayward Gallery in London in 1990, "the ruined objects are ghostly, levitating just above the floor, waiting to be reassessed in the light of their transformation. The title, because of its biblical references, alludes to money, to betrayal, to death and resurrection: more simply it is a literal description of the piece."

The tension between, on the one hand, the muscularity of destructive force (let alone violence of vision) necessary to crush the horde of commemorative keepsakes, and on the other the levitating lyricism of the debris' dazzling display, casting shifting shadowscapes on the floor, is what stops you in your tracks. That fortuitous friction between weighty disfigurement of "ruined objects" and the weightless ballet of shadows, serendipitously cast, is something Parker would endeavour to control more concertedly in subsequent works. "I like shadows and things that are shiny, the opposite of shadows," she tells BBC Culture. "I've always liked nocturnes. The first time I really used lights was my exploded shed. I wanted to make a work with a light source. It's linked to explosion – the flash – so that's where the light first appeared."

![Cornelia Parker Parker has said that we're constantly bombarded with the imagery of the explosion, "from the violence of the comic strip [to] action films" (Credit: Cornelia Parker)](https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/images/ic/480xn/p0cg6n5s.jpg.webp) Cornelia Parker

Cornelia ParkerShe's talking of course about her best-known work, Cold Dark Matter: An Exploded View, created two years after Thirty Pieces of Silver. The installation, which suspends by invisible filaments the shattered contents of a garden shed that Parker had detonated in a field in 1991, is dazzlingly illuminated by a blaring lightbulb positioned at the centre of the twisted and twisting fragments of bikes, garden tools, paint pots and toys, whose silhouettes are projected on to the outer walls of the gallery. Though the work may reference in its title a theoretical concept seemingly at far remove from the urgencies of everyday life ("cold dark matter" is a type of dark matter hypothesised by physicists), there is nothing aloof or remote about the impact of Parker's installation. Observers of the piece find themselves suddenly entangled in the energy of the endlessly suspended explosion, as their own silhouettes are also thrown into the delicate lantern dance of shadows on the outer walls.

We know that the artist's penchant for squashing can be traced back to leaving coins on railroad tracks as a child, but from where does this fascination with silhouettes stem? "Oh, that's from my cave-dwelling days, my Plato's Cave days," the artist answers with a laugh, reminding me that for all their physical and psychological heft and ingenious crafting, there is an inescapable humour at the heart of a career-full of works made from incorrigibly smashing and detonating stuff. It's difficult not to detect a grim smirk behind her slashed torso of a doll of Oliver Twist that she sliced in two with the blade that once slipped through the guillotine that cut things short for Marie Antoinette in 1793 – a prop Parker borrowed from Madame Tussauds. And the notion of using complementary splotches of snake venom and anti-venom to create ambiguous Rorschach-like blots that have the interpretative potential to reveal what's slithering around inside our subconscious is funny. It just is.

That Parker's mercurial mind can range across so many types of media and modes of expression – now framing rumpled handkerchiefs smudged with the tarnish of silverware owned by everyone from Guy Fawkes to Charles Dickens (Stolen Thunder, 1996-7), now using a hot poker to singe folded paper to create a pattern of seared holes (Hot Poker Drawings, 2009-2013) – one may reasonably wonder whether a retrospective of her work can reveal any discernible sense of evolution in style or vision. To survey her oeuvre is to witness a careful accumulation of aesthetic technique and refinement of approach.

Cornelia Parker

Cornelia ParkerOne of the most enthralling works in the show, Perpetual Canon (2004), is a melding of tropes first experimented with in Thirty Pieces of Silver and Cold Dark Matter. Summoning the force of an industrial press 25 times stronger than the steamroller she'd used 15 years earlier, and a forklift truck, Parker crushed 60 tubas, trumpets, coronets and a hulking sousaphone into breathless skins that she arranged like flattened asteroids orbiting around a dangling lamp. "The squashed instruments," Parker tells BBC Culture, "were hung in a ring, in a circle like a marching band. I quite liked the instruments becoming shadows because it means the audience is between the shadows and the objects. You can't tell the objects are squished in the shadows. It's like a ghost band, as it were. The idea of a Perpetual Canon that just keeps going on forever. It's like these wind instruments have inhaled and never exhaled. Like they've just taken a breath and are in an arrested space."

She is drawn to the interplay of light and dark. "I like the imaginativeness of shadows. You become a shadow. The light amplifies all the instruments, they become more cacophonous through that, so it's almost like you're getting visual amplification rather than audial. It's like magnifying everything."

"Magnifying everything" is what Parker does best. Her robust interventions into the lives of objects and her determination to squeeze meaning from the props of existence, never results in a diminishment of an object's power, only an intensification. By pounding the wind out of things, she manages paradoxically to essentialise its breath. And it's a trick she continues to pull off with fresh flair to this day, creating a new installation for the exhibition, Island (2022), that's the final work in Tate's show.

The curiously eclectic piece, which occupies a gallery of its own, is comprised of a greenhouse whose windows have been smudged with strokes of chalk from the White Cliffs of Dover (a recurring material in her work). Strobing in time to the rhythm of one's lungs, a light inside the greenhouse gives intermittent glimpses of the structure's floor, made from discarded tiles designed by Augustus Pugin for the Houses of Parliament in the 19th Century. "It looks a bit like a floating carpet," says Parker. "All the most powerful people in the world have strode across them – Gladstone, everyone. It's been worn thin by politicians. It looks like the greenhouse is afloat on top of this thing." According to Parker, the light pulsates "very slowly, almost like breathing, so shadows fill the walls – a bit like the shed, or Perpetual Canon".

The work is a fitting final note for a show that Parker says "is cementing something". Less overtly aggressive than her crushed and exploded works, Island nevertheless packs a poetic punch, conjuring as it does themes of climate change in the disused greenhouse and fears of cultural isolation in its white-washed windows and wistful floor. Make what you will of the breathing light.

Cornelia Parker is at Tate Britain, London until 16 October 2022.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.