The women who redefined colour

Emmanuel Lafont

Emmanuel LafontFive years before Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's Theory of Colours, the English artist Mary Gartside published her own challenge to the ideas of Isaac Newton – but, writes Kelly Grovier, she has disappeared from history.

In 1805, a little-known English artist and amateur painting instructor did what no woman before her ever had: publish a book on the subject of colour theory. Though frustratingly few details of the life and career of Mary Gartside have survived, her unprecedented volume An Essay on Light and Shade, on Colours, and on Composition in General reveals evidence of extraordinary creative genius. Modestly introduced by its obscure author as little more than a guidebook to "the ladies I have been called upon to instruct in painting", Gartside's study is accompanied by a series of strikingly abstract images unlike any produced previously by a writer or artist of any gender.

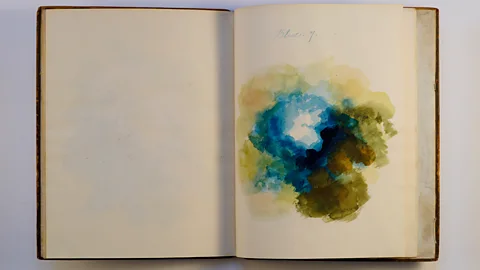

At first glance, you could easily mistake Gartside's eight watercolour "blots" for magnified floralscapes that anticipate the outsized stamens and pistils that the US artist Georgia O'Keeffe would begin exploding out of all proportion more than 100 years later. But look again at these lucent surges of almost petals, whose vibrancy of colour is unshackled to tangible shape, and any certainty you may have had about what it is that these images portray or what they mean begins to break down. Neither fragrant blossoms plucked from the real world nor imaginary blooms unfolding in the mind, Gartside's abstract blots burst beyond the borders of themselves a full century before non-figurative painting established itself on the better-known canvases of Wassily Kandinsky, Kazimir Malevich and Piet Mondrian.

Clive Boursnell

Clive BoursnellMore metaphors for the resplendence of roses than roses themselves, Gartside's abstract blots served a paradoxically precise theoretical function that belies their amorphous beauty. Titled, in turn, "white", "yellow", "orange", "green", "scarlet", "blue", "violet" and "crimson", these evanescent experiments show each "tint at various degrees of saturation", the art historian Alexandra Loske explains in her recent study Colour: A Visual History, "and blending abstractly with others".

Gartside's aim was to illustrate the harmonies and contrasting hues of the primary and secondary colours in a manner that was more organic, and perhaps less scientifically aloof, than the schematised colour wheels of her famous male forebears in the field. While her blots might have, as TS Eliot writes in his 1936 poem Burnt Norton, "the look of flowers that are looked at", in truth they sought, generations before their time, to strip away the self-conscious pretence of settled shape, and instead to isolate the luminous energy that invigorates our perception of all things: colour.

"Colours," the Romantic essayist Leigh Hunt jauntily jotted in 1840, "are the smiles of nature. When they are extremely smiling, and break forth into other beauty besides, they are her laughs; as in the flowers". What is clear from Gartside's pioneering studies is that no theorist had ever listened more intently to the laughter of colour than she did. "There is no other example of a representation of colour systems," Loske writes, "that is as inventive and radical as Gartside's colour blots".

Charlotte Gann

Charlotte GannLoske has devoted herself to restoring to the story of art the achievements of forgotten female writers and artists who, despite historic discouragement of women to take up either the palette or the pen, succeeded in creating some of the most intriguing aesthetic inventions in cultural history. "If somebody can find me an earlier one," she tells BBC Culture, when asked about how certain she is of Gartside's position as the first female author of a theory of colour, "I'd be very happy to hear. She is the earliest, certainly in the Western world."

First among equals

Loske stumbled across Gartside by chance as a graduate student after landing a research fellowship based at the Royal Pavilion in Brighton, where she now serves as curator. "They wanted somebody to look into colour theory," she recalls, "and I spent many happy years doing this doctorate, and all I could find was men's names. And then I came across this one woman and that was Mary Gartside. Just one, and that is what really got me going."

What little we know of Gartside's life and career can be compressed into a sentence or two. Born in 1755, perhaps in Manchester, she eventually taught women how to paint watercolour in London, and managed to show her own work on at least three occasions between 1781 and 1809, at least once at the Royal Academy. In Amy Clampitt's poem, Balms (1980), which recalls a chance encounter with a copy of Gartside's watercolours and the "pungent, velvet-eared succulence" of the "pure hues" they embody, the US poet laments the dearth of biographical detail known about the paintings' creator, writing: "Mary Gartside / died, I couldn't even / learn the year." During lockdown last year Loske kept digging, and finally managed, with the help of colleagues, to pin down the date to 1819. "It was particularly nice to find out about this," Loske says, "because I always thought she died not having been able to enjoy her relative success."

Wikimedia

WikimediaGartside's modestly entitled Essay (which was followed three years later, in 1808, by a revised edition that she boldly rechristened An Essay on a New Theory of Colours, and on Composition in General) predates by half a decade Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's celebrated treatise Theory of Colours, 1810, in which the renowned German poet and critic sought to correct what he believed were basic errors in Isaac Newton's understanding of our experience of colour in the world. Like Goethe, who had been developing his ideas for decades, Gartside seemed quietly determined to recalibrate Newton's conception of the spectrum of colours that comprise white light, which the English mathematician famously hit upon as a student during a much earlier lockdown in 1666, when the Great Plague triggered quarantines, and to inflect it with a painterly urgency and purpose it arguably lacked.

"Calling it a 'theory'," Loske tells me, "is really clever. She puts it into a more serious context, something beyond being a painting manual. She is most interesting in terms of picking up Newtonian ideas and adapting them to painting. Newton was all about immaterial colours – about splitting the rainbow and about coloured lights. Someone had to adapt all of that fantastic knowledge to material colour, and she does that beautifully."

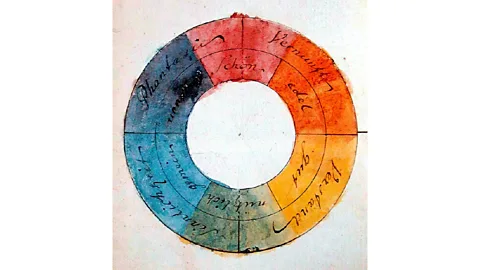

The spectrum of colours that Newton famously unweaved with his carefully angled prisms seemed to many more staged than natural – hues of an obsessive intellect under artificially controlled conditions rather than the dishevelled shades of messy reality. Newton's insistence on bending the rainbow to accommodate a redundant seventh colour, indigo, to sit alongside blue, merely to ensure that there were as many colours as there are the planets in the heavens and notes on the musical scale, is often raised as proof that he shaped what his eyes actually saw to fit an airy ideal. The century between his eventual publication of Opticks: A Treatise of the Reflexions, Refractions, Inflections and Colours of Light – in which Newton formally presents his ideas – and Gartside's and Goethe's volumes on colour theory in the first decade of the 18th Century, would witness a flurry of publications by writers and artists keen to reconcile Newton's clinical notions of colour with the practicalities of actually mixing pigments on a palette.

Refashioning the colour wheel

Central to each of these efforts – undertaken by everyone from the French painter Claude Boutet in 1708 to the British entomologist Moses Harris in 1766 to the Austrian entomologist Ignaz Schiffermüller in 1772 – was a reimagining of Newton's seminal, if curiously colourless, colour circle which he presented in his Opticks. For Goethe, it was Newton's failure to acknowledge the fundamental role that darkness plays in shaping the colours we see in everyday experience that motivated his own refashioning of the colour wheel. In 1798, Goethe and the playwright Friedrich Schiller collaborated on a complex diagram they called the "rose of temperaments", in which the concentric orbits of a dozen colours and corresponding character traits revolve around a dark abyss yawning at the diagram's centre. Eventually this elaborate wheel would give way to Goethe's more famous, simplified colour circle which he devised in 1809 and included the following year in his own Theory of Colours.

Clive Boursnell

Clive BoursnellGartside's abstract roses, which look more like luminous shrapnel suspended mid-explosion than fusty scientific schematics, are far less editorialised or carefully captioned than Goethe's wheels. By erasing the labels that her male precursors inserted into their diagrams, Gartside allows the clashes and harmonies of colour to sing for themselves. By doing so, she reclaims the chromatic diagram as a purely aesthetic document – a work of art.

It is tempting, given the close proximity of the publication dates of Goethe's and Gartside's studies, to wonder whether any cross-pollination of ideas might have occurred – or whether, indeed, Gartside's volume had any influence whatsoever on the ideas or practice of later artists and theorists. Who can say? But it is a question pondered too by Loske, who believes "the abstract dimension of Gartside's illustrations" echo that of JMW Turner, who has himself been seen by historians as a forerunner of non-figurative art. The two contemporaries certainly share a fascination with the heft of weightless colour severed from incidental substance. Turner, Loske suggests, "is likely to have known about her work through his association with a number of watercolour societies," before conceding that, "regrettably, there is no evidence for this".

"No evidence for this" is the dispiriting, if familiar, dead end reached by any critic attempting to assess the contribution of female artists and writers whose achievements have either been overlooked entirely, demeaningly dismissed, or dishonestly unacknowledged. Such are the three sad axes against which the genius of women has all too often been plotted by cultural history. It's a designation where one finds too the tantalising legacy of the US artist and painter Emily Noyes Vanderpoel, whose remarkable ideas and work Loske has also spent time resuscitating.

Alamy

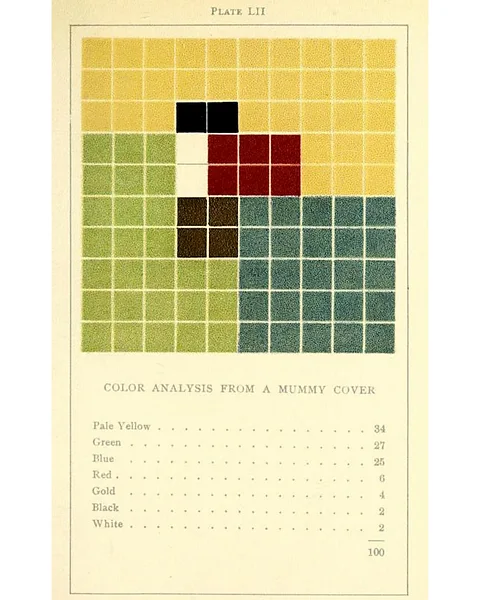

AlamyLike Gartside a century before her, New York-based Vanderpoel surrounded herself with amateur water colourists, and published a deceptively unassuming study of colour whose interior illustrations, properly analysed and appreciated, confound the chronology of modern art milestones. What distinguishes Vanderpoel's Color Problems: A Practical Manual for the Lay Student of Color, published in 1902, are sequences of "colour analyses" in which, Loske has written, "Vanderpoel breaks down an image, an object, or a design pattern into its chromatic components, and presents the resulting colour key on a 10 x 10 square grid, with the proportional distribution of each colour noted below to the total of 100 squares." The result is a series of striking schematics – QR-code-like matrices of pure pixelated colour that predate the geometric abstractions of Piet Mondrian and his minimalist descendants.

To measure fully the significance of either Vanderpoel or Gartside to the unfolding story of art will require the kind of scholarly attention that is lavished on those with a much higher profile – a Catch-22 that Loske is determined to rectify. "I want to create a canon," she says of her wider ambition, "of women who have written on colour. With women there is a whole range of problems: the logistics, how do you get an education, how do you get access to resources, who lets you write, who lets you publish." The picture that Loske is patiently assembling, with each forgotten female figure a stroke on her canvas, promises to challenge the image we have in our minds of whose palettes truly shaped the shapes of art. I can't wait to see it.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.