The children's book that's really for adults

Kristjana S Williams

Kristjana S WilliamsFor more than 150 years, Lewis Carroll's Alice stories have captured the imaginations of readers, artists, filmmakers and designers. Holly Williams finds out why.

For books that are all about surprising transformations, it should perhaps be no real surprise that Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass are among the most frequently adapted and reinterpreted stories ever written. Alice falls down a rabbit hole, and steps through a mirror, into worlds where anything can happen, where even the sense of self is transformed: where a drink can make you shrink and a mushroom can make you grow; where babies turn into pigs and a little girl can become queen; where flowers and animals and playing cards all speak but logic and learning slip out of grasp.

More like this:

No wonder then, really, that reinventing Lewis Carroll's fantastical, nonsensical creations into new forms has always proved irresistible. Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, published in 1866, and its equally delightful 1871 sequel, Through the Looking-Glass, have inspired generations of artists working in all sorts of media, from film to theatre, fine art to pop music. And it's this ongoing legacy that forms the basis for the latest blockbuster museum show about Carroll's creation. Alice: Curiouser and Curiouser opens at the V&A in London this month, having been much delayed by Covid-19.

V&A

V&A"The starting point for an exhibition is usually 'why' – why has Alice triggered so many different creative responses?" says Kate Bailey, the curator. "I started by looking at the impact of Alice, and thinking about the broader cultural, socio-political contexts – why and when it's had these different interpretations and activations. You're looking for those trigger moments, that move it on in our collective consciousness."

Alice and Wonderland does very much live in our collective consciousness. We all know what a Mad Hatter's tea party looks like, can liken hapless pairs to Tweedledum and Tweedledee, or a big grin to a Cheshire cat. The image of a little blonde girl in a blue dress and an Alice band is always and inevitably, well, Alice. (Yes, the headband is named after her).

Alice's Adventures in Wonderland began, so the story goes, when Charles Lutwidge Dodgson – aka Lewis Carroll – wove a yarn to entertain a real child named Alice Liddell and her sisters one summer's afternoon in 1862. And yet for many readers, neither Alice nor Wonderland are ever really consigned to childhood, but rather carried affectionately into adulthood. I have a Queen Alice T-shirt; I know more people with tattoos inspired by the tale, from "Drink me" bottles to smoking caterpillars, than from any other single source. Lines are re-interpreted in the modern age as Instagrammable inspirational quotes ("Sometimes I've believed as many as six impossible things before breakfast"), and some adaptations are distinctly for adults only, as we shall see, with artists finding potent metaphors in Carroll's tale.

But from its very first publication, Alice broke the bounds of "children's literature", to the extent that The Nation newspaper was able to suggest the book was more for adults than children, really. Carroll knew what he was doing here: he'd made the canny decision to have it illustrated by John Tenniel, who was not associated with children's books – rather, he was famous as a Punch cartoonist, sending up political figures. Tenniel was the more powerful in the relationship – he was so unhappy with the quality of the initial print run that he insisted it be redone at great cost. The publication of Through the Looking-Glass, meanwhile, took so long because Carroll had to wait for his schedule.

V&A

V&A"There was a sense of 'is this book just for children or is it for adults?'" says Bailey. "Going with the illustrator from Punch and the appeal to the adult audience was obviously partly in Carroll's mind. It was very strategic."

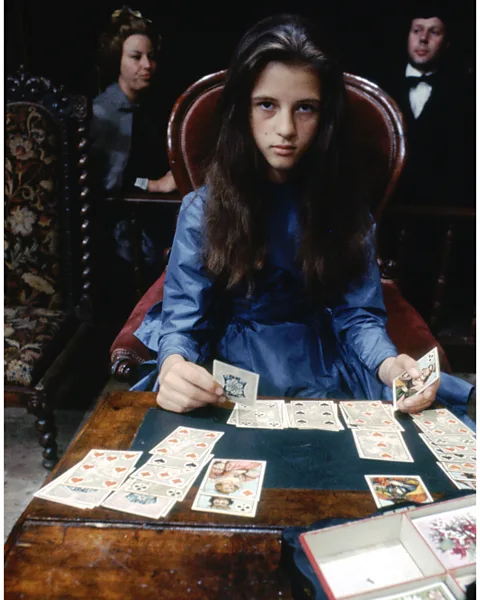

Tenniel's distinctive, often beautiful, often slightly-unnerving black-and-white wood engravings were instantly – and enduringly – popular. Perhaps he would be surprised at the number of items on Etsy today that bear his images, but maybe not: very quickly after publication, Tenniel's images were widely used in Victorian merchandise. The V&A show features examples of original Alice "branding", from biscuit tins to playing cards.

Adapting Alice

From the very beginning, then, the image of "Alice" has always been central. Tenniel certainly set an extremely high bar for illustrations – and he established many of the Wonderland tropes that endure across every medium, from her pinafore dress to the Hatter's top hat. Part of the reason Alice is so easily re-imagined is because she is so codified in the first place – something artists both use and subvert.

Some things we think of as distinctly Alice in Wonderland don't come from Tenniel, however. The process of adapting Alice began quickly – the first stage version was mounted in 1876 – but Bailey points out that the tradition of having a blonde Alice "didn't take effect till Hollywood, when there was a definitive actress 'type'". Ruth Gilbert, Charlotte Henry and Carol Marsh played ultra-feminine Alices with long flowing locks in live-action films, released in the 30s and 40s.

But it was surely the full-colour 1951 Disney animation that set the trend for blonde hair in stone, and it was also Disney that established Alice wears a blue dress (the first colour version of the book actually used yellow). And if you think the Cheshire cat "should" be pink and purple, or expect the White Rabbit to say "I'm late! I'm late! For a very important date!"… that's Walt too.

Disney

DisneyThe Alice we expect today may have had the Hollywood treatment along the way, then, but one of the most striking things about the characters of Wonderland is how very easily they morph and bend to an artist's vision, while still remaining recognisable.

More than 300 illustrators have offered their Alices: from Arthur Rackham's whimsical fairy-child vision in 1905 to Moomins' author and illustrator Tove Jansson's softer, more impressionistic take in 1966 to political cartoonist and children's illustrator Chris Riddell's version published last year, where the heroine looks a good deal more like the actual Alice Liddell. Some artists bring their own styles, irrepressibly, to bear: Salvador Dalí's series features his iconic floppy clock; Ralph Steadman's Mad Hatter and March Hare look like they've come straight out of his infamous illustrations for Hunter S Thompson's Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, while Yayoi Kusama's 2012 book features more of her trademark polka dots and pumpkins than most Wonderlands.

Despite the original stories' reliance on wordplay, puns, and nonsense, Alice has become such an icon that she is often used as a touchstone even within primarily visual media. When Christopher Wheeldon first suggested a ballet version, his designer Bob Crowley reportedly thought he was "completely insane" to make a wordless Wonderland. But the Royal Ballet's 2011 show was a huge hit – not least because of Crowley's designs, which combined familiar Alice shorthands with classical tutus and cutting-edge stagecraft, from op-art projections to a multi-part Cheshire cat puppet. The Queen of Hearts stepped out of an intimidatingly huge crinoline-cum-throne-cum-tank, to dance a parody of a sequence from the ballet Sleeping Beauty: both very Lewis Carroll, and very ballet.

'Magic and mystery'

Alice has long been a touchstone for fashion, too. Vivienne Westwood, Zac Posen, Viktor & Rolf, and John Galliano have all sent looks down the runway inspired by Caroll's characters and Tenniel's drawings, while the transformative, otherworldly possibilities of Wonderland hold appeal for fashion shoots.

"I think a lot of people are inspired by the magic and mystery and the craziness of the story of Alice," said legendary Vogue creative director Grace Coddington in a recent online talk. In 2003, she directed a shoot by Annie Leibovitz for Vogue, in which fashion designers were assigned Wonderland characters. "There was Stephen Jones as a Mad Hatter; Viktor and Rolf as Tweedledee and Tweedledum. John Paul Gaultier was the Cheshire cat because he's always smiling and always wearing stripes," recalled Coddington.

Reinventing Alice isn't just a visual matter however: the act of reinterpreting inevitably brings wider cultural and social preoccupations into play. In 2018, Tim Walker shot a Wonderland series for the Pirelli calendar using an entirely black cast, including model Duckie Thot as Alice, RuPaul as the Queen of Hearts, and Whoopi Goldberg as the Duchess. The shoot took its power from the unfamiliarity of having a black cast inhabiting the extremely familiar Alice in Wonderland archetypes.

Tim Walker Studio courtesy of Pirelli

Tim Walker Studio courtesy of Pirelli"I had never seen a black Alice, so I wanted to push how fictional fantasy figures can be represented and explore evolving ideas of beauty," Walker is quoted as saying in the V&A's catalogue.

Alice has often become a site or symbol of broader societal change. Bailey points out that one of the earliest co-optings was by the Suffragettes; she found the 1911 play Alice in Ganderland in the V&A's archive, "which showed how Alice became a heroine for the new century's new woman". The production was part of a campaign for equal pay.

In the 30s and 40s, Carroll's story became a foundational text for a new artistic movement. The Surrealists, drawing on Freud's theories of the unconscious, were unsurprisingly also drawn to Carroll's illogical dream narratives. A Guardian review of the first Surrealist show in the UK in 1936 even used Alice to explain their paintings: "If a Lewis Carroll can create a world of hookah-smoking caterpillars, mimsy borogroves, and gimbling toves, why should not a Max Ernst or a Joan Miró find the equivalent of such a world in paint?"

Paintings by Ernst, Edward Burra, Leonora Carrington, and Dorothea Tanning are probably the interpretations that take us furthest away from the Tenniel/Disney axis, amping up the sinister or unsettling aspects of Wonderland by playing with scale and uncertainty. Here are cavernous corridors, looming outsized faces, creepy little girls with their hair standing on end. This is the treacly sludge of the subconscious, rather than Victorian whimsy – but re-read Carroll's stories, and there is plenty of frustration, fear, and genuine danger among the silliness.

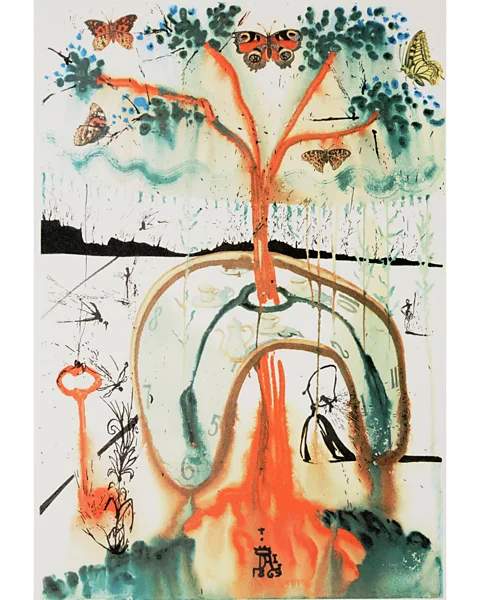

Salvador Dalí's watery, abstracted illustrations of Alice in Wonderland came later, in 1969 – by which time, Alice was enjoying another cultural "moment". Wonderland was roundly co-opted as a psychedelic experience: a mind-expanding hallucination, where creatures talk and your body changes and you feel compelled to question who you even really are.

Salvador Dali / Dallas Museum of Art

Salvador Dali / Dallas Museum of ArtAlice interpretations abound in this era. Adrian Piper and Joseph McHugh made Alice-inspired works in the characteristic swirling hot pinks and oranges of psychedelic art. Musicians got in on the act, from Jefferson Airplane's delicious, droning 1967 hit White Rabbit though to The Beatles' I am the Walrus, with John Lennon inspired by the poem The Walrus and the Carpenter from Through the Looking-Glass. Ralph Steadman's illustrations duly depict Lennon himself as the caterpillar, while German artist Sigmar Polke collaged Tenniel's original caterpillar into his trippy, polka-dotted works. There's more dottiness in Yayoi Kusama's 1968 "happening", where naked, spot-painted performers cavorted around the Alice statue in Central Park. "Alice was the grandmother of hippies. When she was low, Alice was the first to take pills to make her high," Kusama stated, spelling it out somewhat.

Down the rabbit hole

All this enduringly transformed our understanding of Alice, to the extent that originally innocent elements are now often used as references to mind-altering substances: the smoking caterpillar, the mushrooms, chasing the white rabbit… Indeed, in 1971 a US government educational film, Curious Alice, depicted characters from Wonderland as different drug addicts: the caterpillar hooked on weed; the March Hare on amphetamines; the dormouse on barbiturates. It was intended to warn children away, but instead achieved cult status for being an appealingly trippy, swirling piece of psychedelia in its own right.

Not all Alices of the era were groovy, however – Peter Blake's illustrations from 1970 may flutter with colourful flowers and pattern, but their overall mood is sombre. Alice stares down the viewer rather mournfully; the Mad Hatter looks sorry for himself in jail. Despite their colour, they feel of a world with Jonathan Miller's strange 1966 BBC adaptation. Filmed in sober black and white, with all characters played as recognisable (usually upper-class) "types" rather than animals, of all the Alice adaptations it most truly feels like a dream. But unless you know the original very well, it would be incomprehensible, and is unlikely to appeal much to children.

Miller brings a foreboding atmosphere to proceedings, and homes in on the idea of Wonderland as an illogical adult world that a child struggles to navigate. Still, as a satire of a society bound by pointless conventions imposed by the ruling classes, it does feel like a distinctly 1960s interpretation – as does the sitar soundtrack from Ravi Shankar.

And Alice in Wonderland as coming-of-age story is something often brought out in narrative adaptations on stage and screen, or even on record – Little Simz's 2017 concept album Stillness in Wonderland used Alice as a framework for self-discovery.

But Alice's potential as a symbol for puberty (all those bodily changes!) or incipient womanhood is also something that's attracted more troubling perspectives. Anna Gaskell's series of photographs of young Alice-a-likes – sometimes bullying each other, or their bodies physically entangling – disturb and disrupt the idea of the innocent girl child.

Solomon R Guggenheim Museum, courtesy of Galerie Gisela Capitain

Solomon R Guggenheim Museum, courtesy of Galerie Gisela CapitainThe most recent Alice interpretations continue to reflect the times she's read in – so it's no wonder she's gone digital in the 21st Century. American McGee's dark computer game casts Alice as a traumatised action heroine, battling villains such as the Jabberwock and the Queen of Hearts in her dark unconscious. In Damon Albarn's musical wonder.land, going down the rabbit hole transformed into being sucked into a digital world, with a lonely teenager adopting Alice as an avatar in an online game.

"Wonderland is always a powerful metaphor or idea to work with," says Bailey. And that's what the V&A show is interested in: how one man's nonsensical story, made up to entertain a little girl, has allowed so many generations of readers and so many restlessly reinventing artists to go down the rabbit hole of their own imagination.

"The book has such a phenomenal number of ideas and concepts in it, but it creates space for the creativity too," says Bailey. "It really is this Bible for the imagination."

Love books? Join BBC Culture Book Club on Facebook, a community for literature fanatics all over the world.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.