How masks have appeared in art

Zabou/Getty Images

Zabou/Getty ImagesFrom social media to street art, masks are cropping up everywhere. Deborah Nicholls-Lee finds images around the world reflecting what’s going on now.

A profile picture with a covered mouth greets visitors to the Instagram page of Cypriot visual designer Hayati Evren. The mash-up artist has taken virtual scissors and glue to his own image, and superimposed a bright blue surgical mask on an otherwise monochrome photograph.

Hayati Evren

Hayati EvrenThe playful artist, who has been meddling with masterpieces for almost a decade, is best known right now for his cheeky Corona Lisa, who sips a Corona beer through a pierced face mask. Alongside Oregon-based Antonio Brasko’s teetotal version, the meme has spread from social media to T-shirts, bags and mugs. The Persistence of Corona, Evren’s reworking of an iconic Salvador Dali work, places the mask centre stage again, this time surrounded by other accoutrements of coronavirus management: hand sanitiser, rubber gloves, and lemon cologne – a traditional disinfectant in Turkey.

Since the outbreak of Covid-19, the mask – the emblem of the pandemic – has fed the creativity of artists worldwide, taking multiple forms from humorous meme to serious statement. Obligatory in some countries and initially discouraged in others, the mask is an object of controversy: a symbol of censorship and separation, but also of care and protection.

PA

PAWhile social media has been the playground of digital artists such as Evren, the street too has become a gallery for mask art. Recently, the gently parted lips of Banksy’s Girl with a Pierced Eardrum were concealed overnight behind a protective fabric face mask. The giant mural, a riff on Vermeer’s Girl With a Pearl Earring but with a security alarm for a piercing, first appeared in Bristol’s Albion Dock in 2014. Whether the gesture was a loving act of preservation or the cynical mocking of our fears, Banksy has denied any involvement.

Hijack

HijackIn the Pico-Robertson neighbourhood of Los Angeles, graffiti artist Hijack recently spray-painted two masked figures in boiler suits wielding spray detergent, a feather duster and a vacuum cleaner as weapons against the virus – a wry comment, no doubt, on our impotence. “In times like this, creativity can help us deal with … a crisis like the one we’re in,” he tells BBC Culture. “The piece itself is more of an observation of our current mental state. We seem to be waging a war against an unseen enemy sending some of us into panic. I wanted to convey this in typical Hijack fashion.”

That panic, suggests German photographer Marius Sperlich, can sometimes be blind. Sperlich, whose work typically explores the human body close up, has his model’s eyes, ears and mouth covered by white surgical masks in a recent photograph titled Isolation. Commenting on the post on Instagram, he writes: “Our senses have been restricted, we’re isolated and afraid, incapable of rational thoughts.”

Zabou

ZabouWhile new works structured around the face-mask meme have been multiplying, existing pieces featuring masks have also gained new audiences. Zabou’s 3m² portrait of fellow street artist BK Foxx wearing her respirator mask brought colour to London’s Brick Lane in early 2019, but the French artist’s mural has acquired a new significance during the pandemic, and is now seen as an iconic image of the crisis. The face mask, Zabou tells BBC Culture, has now become part of our daily lives. “It represents a tool of action and protection – and sometimes survival – against the virus, which is why masks can be a powerful image in this context.”

Rachel List

Rachel ListIn some cases, the power of the face-mask image has thrust lesser-known artists into the spotlight, and made heroes of the humble. Twenty-nine-year-old Rachel List from Pontefract in West Yorkshire tagged her giant mask mural with #itwasntbanksy to end speculation that had started when her preceding series of wall paintings of a little cartoon NHS nurse in a face mask trended on Twitter.

List, who earns her living by painting murals in children’s bedrooms, had seen her work dry up since lockdown, but a commission for an NHS appreciation banner for a local pub led to a series of requests for her cheerful tributes to the health service. List is giving away prints to 500 NHS workers, and raising funds for the NHS and the Prince of Wales Hospice through auctions of her work. “For me, what’s striking about the face mask is you can’t see people’s smiles. It brings the focus back to the eyes, which makes it really expressive,” she tells BBC Culture.

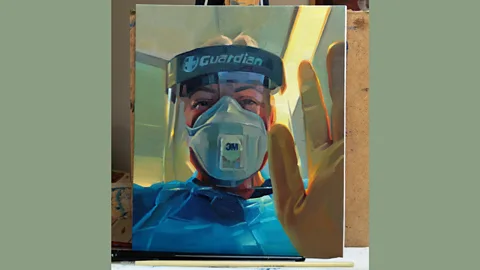

Tom Croft

Tom CroftOxford-based portrait painter Tom Croft also used his skills as an artist to acknowledge the sacrifice being made by care workers during the crisis. When the pandemic left him struggling to find purpose in his work, he decided to offer a free portrait to the first NHS worker to contact him. Harriet Durkin, an A&E nurse from Manchester Royal Infirmary, was soon immortalised in oils in full PPE, with her chunky 3M face mask centre frame. Using the hashtag #portraitsforheroes, Croft invited other artists to join the initiative and pair up with frontline workers.

Croft’s feelings about the mask are ambivalent. “The mask protects, hopefully, but it also creates a barrier between patient and health worker, and impacts the human connection we’re used to, which is a huge part of care,” he tells BBC Culture. “Only seeing the eyes, it’s far harder to read the facial expression underneath. I understand that this can cause additional anxiety for the patients.” Croft plans to produce a second portrait of Harriet out of her PPE, relaxed and smiling at home. “I felt it was important to describe both sides to her, to give a fuller picture of who’s behind the mask providing the care,” he says.

Rowena Dring

Rowena Dring“One of the jokes amongst my friends is that I just pivoted my skill set,” says Amsterdam-based artist Rowena Dring, who also saw the pandemic as a call to action. Dring’s ambidextrous approach, which draws on traditional handicraft skills to re-contextualise stitching and painting, took a new turn when she united function and art to answer the shortage of face masks.

“I am a maker: someone who responds to situations by making things,” she tells BBC Culture. “I researched very carefully the materials that I used with the help of a doctor, but at the same time, I wanted to make people laugh.” The result was an ever-expanding collection of beeswaxed cotton canvas masks embroidered with curly moustaches, shaggy beards, and smiles. As the new designs tumbled out of her improvised home workshop, they were shipped to friends and family or sold to online customers. “I like the smiley ones,” she says. “It’s very funny going into the supermarket with those.”

The face mask has also influenced fashion design. In April, Nigerian fashion designer and celebrity stylist Tiannah Toyin Lawani created a dazzling masked outfit to increase awareness of the virus. Lawani now has a team of tailors working from her home in Lagos – where masks are now compulsory – making jewel-encrusted masks from African fabrics for sale or donation.

Max Siedentopf

Max SiedentopfHomemade face masks were the inspiration behind a series of tongue-in-cheek photographs produced by Namibian-German visual artist Max Siedentopf in his controversial series How To Survive a Deadly Global Virus. “I started seeing online all kinds of DIY masks to protect against the virus which were made of common household objects,” he tells BBC Culture. “In the middle of this crisis, I wanted to focus on the creativity of these masks and how through a barrier or problem you can still find smart and creative solutions.”

Criticised for being insensitive and misleading, the images have appalled some and inspired others. But watching from the wings, Siedentopf was amazed as photographs emerged of people replicating the masks in the series. “I liked how art imitated life and then life imitated art and became full circle,” he says.

Tatsuya Tanaka

Tatsuya TanakaIn Japan, the face mask has become a household item and has found its way into the intricate work of Japanese miniature artist Tatsuya Tanaka, who combines real-size everyday objects with 2cm-tall human figures. Since 2011, Tanaka has been releasing daily images as part of an ongoing Miniature Calendar series. On 31 March, a photograph of tiny surfers riding a tidal wave of masks was posted with the caption “we overcome many difficulties”. The face-mask motif reappeared on 1 May when Tatsuya released an image of a masked doctor doing a video consultation on a chocolate computer.

With many countries on lockdown, mundane household items are resonating with artists and audiences more than ever. “Making what you casually see in everyday life different – called ‘mitate’ in Japan – makes everyday life fun,” Tatsuya tells BBC Culture. “I was using masks on a daily basis in Japan since before the crisis. It’s not uncommon, but I got a lot of attention because of the corona[virus] crisis, so I made it a motif,” he says.

Hasan Kale

Hasan KaleThe work of Turkish micro-artist Hasan Kale also forces a re-evaluation of familiar objects. Holding his breath to steady his hand, he paints portraits and landscapes on minuscule oddments such as matchstick heads and apple pips, turning them into what he calls “art capsules”.

Kale’s recent canvases have included a paracetamol tablet and the valve of a surgical face mask, both painted with images of masked health workers as a mark of gratitude for their service to society. A close inspection of the tablet reveals that the masks have not prevented their wearers from communicating a microscopic message on behalf of the artist. “We have seen the harm that we have done to the world,” says Kale. “The coronavirus is an opportunity for us to be better.”

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.