Earth Day at 50: The best ways to change the world

Michael Pinsky/ Thor Nielsen/Cape Farewell

Michael Pinsky/ Thor Nielsen/Cape FarewellCampaigners recognise that often the most effective way to tackle climate change is through our emotions – something artists can tap into, writes Gaia Vince in the second of our series celebrating 50 years of Earth Day.

For Deanna Witman, art has become the most essential way to document the changes we are making to our planetary environment. She uses photographic installations to raise awareness of the speed of climate change and urge action through an emotional engagement.

Witman is a scientist by training, and her new vocation is quite a departure from her last job, where she worked as a field biologist, carrying out environmental impact studies for transportation and infrastructure projects. For more than a decade, Witman collected data at the location being considered to understand how the potential work would affect the surrounding area.

Deanna Witman

Deanna Witman“It took its toll on me. I became very aware – very attuned – to these environments and began to identify with them,” she says. “Seeing really exceptional habitats being impacted had a deep subconscious impact on me. But I also felt that I was providing the best information that I could – that I was, sort of, the truth teller – about how these projects would potentially change those areas and species.”

Witman reached a crisis point, some 15 years into her career, where she became overcome with grief and a sense of loss about the human impacts on the natural world. It led her to switch from science to art, feeling it gave her a way to process the emotions that ecological destruction provoked – and a more effective way to communicate the need for action on sustainability.

“It’s an existential sort of crisis if your world is being impacted. And I’m partly responsible for that, so there’s huge amounts of guilt involved along with the anxiety and the grief,” she explains. “Once I understood that I was grieving, it kick-started my ability to make art.”

Emotional crisis

Witman’s art is an attempt to document the changes humans are making to our environment, and raise awareness of its speed. Now an assistant professor in environmental humanities at Unity College, Maine, she hopes to prompt dialogue with her creations about our relationship and responsibility to the natural world. One of her projects, Melt, was inspired by reading a New York Times article that looked at past Winter Olympics sites and considered how many would be ruled out by 2050 for want of ice. For this, she collected Google Earth satellite images of these and other glacial sites, and printed them onto unfixed salted paper, causing them to symbolically fade over the duration of the three-month exhibition.

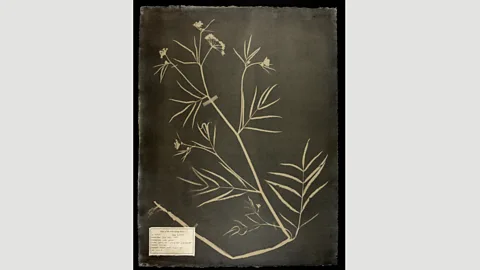

Deanna Witman

Deanna WitmanHer latest project, Index, feels more personal. “I live along a tidal river that’s experiencing the fastest rising water temperatures in the world. So I decided to collect one of each plant species that I could find in a little patch of threatened intertidal marsh and photograph them using a gum-dichromate process before they disappear.” The result is a haunting catalogue of loss, impeccably referenced with scientific names and information.

Deanna Witman

Deanna WitmanArtists have always responded to their environments, of course. But the increasing urgency and scale of the climate crisis are driving them to engage in new ways with the science (and scientists) involved. This is a participatory form of expression, in which artists are not simply portraying their response to environmental change but actively fighting the transformation itself.

Antarctica may not seem the obvious choice for an art installation. The continent has no permanent residents, and its small, temporary population is made up of busy research scientists, not touring art lovers. Nevertheless, the innovative art installation, Glaciators, ran there for several months in 2017. Conceived by Argentinian artist-engineer Joaquín Fargas, the Glaciator is a shiny silver robot, coated in solar panels, that accelerates the formation of glacial ice by compacting powdery snow beneath it into harder crystals.

Joaquín Fargas

Joaquín FargasGlaciators has a symbolic function – it will not replace the ice lost to global warming, of course, but it draws attention to the problem of anthropogenic ice melt in a very direct way, and points to the role – and limitations – of technology in addressing such an enormous challenge. Another of Fargas’s installations, Rabdomante (meaning: dowser), is a solar-powered robot that travels the bone-dry Atacama Desert, creating water droplets from the atmosphere. These symbolic uses of technology are powerful because of their impotence – they capture the futility of simple technological answers to complex planetary problems that were created by humans.

Other artists seek the inspiration to produce sustainable societal change by fully immersing themselves into the raw environment they are portraying. The Cape Farewell project, created by British artist David Buckland, is a collaboration of scientists, artists, writers and poets who physically explore examples of our possible futures, from fragile natural landscapes to functional cleantech industries and sustainable island communities. The idea is to produce works that engage the imagination of the public to drive cultural and environmental change.

Michael Pinsky/ Thor Nielsen/Cape Farewell

Michael Pinsky/ Thor Nielsen/Cape FarewellThe results can be affecting, as the science is given emotive and sensory form. Pollution Pods, a recent touring installation by Michael Pinsky, consisted of five interlinked, climatically-controlled glass domes, each of which was filled with the recreated air chemistry of world cities: London, New Delhi, Beijing, São Paulo, and Tautra (Norway). Walking through these five environments is to experience instant contrasts: from breathing the clean Arctic island air of Tautra to the filthy, unhealthy sulphur dioxide, smog, carbon monoxide and other pollutants that fill most of our major cities.

Another of Cape Farewell’s projects reimagines farmland, in which artists and scientists will research the river flows through Dorset agricultural land to understand how food production can be better managed to reduce run-off pollution and algal blooms downstream. For The Watershed, artists will be based in an ‘experimental station’ in a converted trout farm, fully surrounded by the water they are investigating.

Michel Comte

Michel Comte“Time and apathy are the biggest challenges we face in the race against climate change; arts and culture possess an unique power to inspire and to shake up, to share ideas and to unite in a common cause,” according to the acclaimed photographer Michel Comte, who has worked in warzones around the world as well as capturing everyone from Miles Davis to Cindy Crawford. Now, though, he has a new muse: Earth. Comte has worked with the Wavelength Foundation of artists and scientists, which aims to “embed and to advance environmental thinking and climate change awareness in contemporary culture”. Its Change Maker scheme awards cultural and artistic projects that directly influence politics and politicians to improve decision-making with regards to the environment and climate change. In 2021, as a solo project Comte hopes to create a 3D mapping light installation project in the Arctic, called Black Light, to highlight the vulnerability of this changing icescape.

Mitch Joachim/ Terreform ONE/ Art Works for Change

Mitch Joachim/ Terreform ONE/ Art Works for ChangeEnvironmental activists have long drawn on scientific data to help make their case, but they also recognise the power of art to transform public opinion and inspire the kind of transformational change needed to fight climate change. Several conservation organisations are collaborating with artists, including WWF and Greenpeace. Art Works For Change is a collaboration of artists, organisations and institutions to inspire a collective force for change. One of their recent exhibitions, Survival Architecture and the Art of Resilience, called on science, technology, architecture and art to imagine buildings that address the challenges of excess heat, droughts, flooding, and food insecurity. Among them is a striking white structure that resembles a large conch shell, but is a modular edible insect farm made from plastic containers.

“Artists are the blazing moral voices of a society,” says Lauren Groff, founder of Greenpeace’s Climate Visionaries Artists’ Project. “If our artists are focused mainly on the urgencies of 30 years ago, they are abdicating their moral responsibilities. All of us collectively need to act; all of us individually need to act. Yes, it is sometimes hard to know where to start. We say: to make art, to write an essay, to draw, to take a photograph, to engage in a real and thoughtful way with climate change, is one way we can all move forward.”

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.