The insect that painted Europe red

Alamy

AlamyTruly vibrant red was elusive for many years: until a mysterious dye was discovered in Mexico. Devon Van Houten Maldonado reveals how a crushed bug became a sign of wealth and status.

Although scarlet is the colour of sin in the Old Testament, the ancient world’s elite was thirsty for red, a symbol of wealth and status. They spent fantastic sums searching for ever more vibrant hues, until Hernán Cortés and the conquistadors discovered an intoxicatingly saturated pigment in the great markets of Tenochtitlan, modern-day Mexico City. Made from the crushed-up cochineal insect, the mysterious dye launched Spain toward its eventual role as an economic superpower and became one of the New World’s primary exports, as a red craze descended on Europe. An exhibition at Mexico City’s Palacio de Bellas Artes museum reveals the far-reaching impact of the pigment through art history, from the renaissance to modernism.

Alamy

AlamyIn medieval and classical Europe, artisans and traders tripped over each other in search of durable saturated colors and – in turn – wealth, amid swathes of weak and watery fabrics. Dyers guilds guarded their secrets closely and performed seemingly magical feats of alchemy to fix colours to wool, silk and cotton. They used roots and resins to create satisfactory yellows, greens and blues. The murex snail was crushed into a dye to create imperial purple cloth worth more than its weight in gold. But truly vibrant red remained elusive.

For many years, the most common red in Europe came from the Ottoman Empire, where the ‘Turkey red’ process used the root of the rubia plant. European dyers tried desperately to reproduce the results from the East, but succeeded only partially, as the Ottoman process took months and involved a pestilent mix of cow dung, rancid olive oil and bullocks’ blood, according to Amy Butler Greenfield in her book, A Perfect Red.

Dyers also used Brazilwood, lac and lichens, but the resulting colours were usually underwhelming, and the processes often resulted in brownish or orange reds that faded quickly. For royalty and elite, St John’s Blood and Armenian red (dating back as far as the 8th Century BCE, according to Butler Greenfield), created the most vibrant saturated reds available in Europe until the 16th Century. But, made from different varieties of Porphyrophora root parasites, their production was laborious and availability was scarce, even at the highest prices.

Alamy

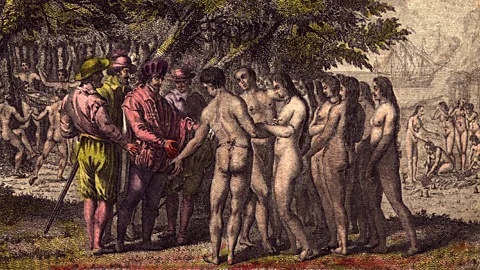

AlamyMesoamerican peoples in southern Mexico had started using the cochineal bug as early as 2000 BCE, long before the arrival of the conquistadors, according to Mexican textile expert Quetzalina Sanchez. Indigenous people in Puebla, Tlaxcala and Oaxaca had systems for breeding and engineering the cochineal bugs for ideal traits and the pigment was used to create paints for codices and murals, to dye cloth and feathers, and even as medicine.

Cochineal in the New World

When the conquistadors arrived in Mexico City, the headquarters of the Aztec empire, the red colour was everywhere. Outlying villages paid dues to their Aztec rulers in kilos of cochineal and rolls of blood-red cloth. “Scarlet is the colour of blood and the grana from cochineal achieved that [...] the colour always had a meaning, sometimes magic other times religious,” Sanchez told the BBC.

Cortés immediately recognized the riches of Mexico, which he related in several letters to King Charles V. “I shall speak of some of the things I have seen, which although badly described, I know very well will cause such wonder that they will hardly be believed, because even we who see them here with our own eyes are unable to comprehend their reality,” wrote Cortés to the king. About the great marketplace of Tenochtitlan, which was “twice as large as that of Salamanca," he wrote, “They also sell skeins of different kinds of spun cotton in all colours, so that it seems quite like one of the silk markets of Granada, although it is on a greater scale; also as many different colours for painters as can be found in Spain and of as excellent hues.”

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesFirst-hand accounts indicate that Cortés wasn’t overly smitten with cochineal, more concerned instead with plundering gold and silver. Back in Spain, the king was pressed to make ends meet and hold together his enormous dominion in relative peace, so, although he was at first unconvinced by the promise of America, he became fascinated by the exotic tales and saw in cochineal an opportunity to prop up the crown’s coffers. By 1523, cochineal pigment made its way back to Spain and caught the attention of the king who wrote to Cortés about exporting the dyestuff back to Europe, writes Butler.

“Through absurd laws and decrees [the Spanish] monopolised the grana trade,” says Sanchez. “They obligated the indians to produce as much as possible.” The native Mesoamericans who specialised in the production of the pigment and weren’t killed by disease or slaughtered during the conquest were paid pennies on the dollar – while the Spaniards “profited enormously as intermediaries.”

Red in art history

Dye from the cochineal bug was ten times as potent as St John’s Blood and produced 30 times more dye per ounce than Armenian red, according to Butler. So when European dyers began to experiment with the pigment, they were delighted by its potential. Most importantly, it was the brightest and most saturated red they had ever seen. By the middle of the 16th Century it was being used across Europe, and by the 1570s it had become one of the most profitable trades in Europe – growing from a meagre “50,000 pounds of cochineal in 1557 to over 150,000 pounds in 1574,” writes Butler.

Alamy

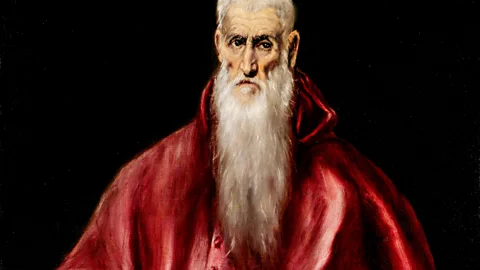

AlamyIn the Mexican Red exhibition at the Palacio de Bellas Artes, the introduction of cochineal red to the European palette is illustrated in baroque paintings from the beginning of the 17th Century, after the pigment was already a booming industry across Europe and the world. Works by baroque painters like Cristóbal de Villalpando and Luis Juárez, father of José Juárez, who worked their entire lives in Mexico (New Spain), hang alongside the Spanish-born Sebastián López de Arteaga and the likes of Peter Paul Rubens.

Wikimedia

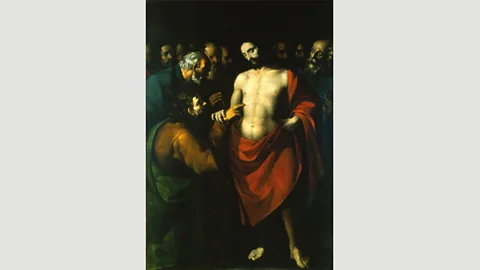

WikimediaLópez de Arteaga’s undated work The Incredulity of Saint Thomas pales in comparison to Caravaggio’s version of the same work, where St Thomas’s consternation and amazement is palpable in the skin of his furrowed forehead. But the red smock worn by Christ in López de Arteaga’s painting, denoting his holiness, absolutely pops off the canvas. Both artists employed cochineal, the introduction of which helped to establish the dramatic contrast that characterised the baroque style.

Alamy

AlamyA few steps away, a portrait of Isabella Brandt (1610) by Rubens shows the versatility of paint made from cochineal. The wall behind the woman is depicted in a deep, glowing red, from which she emerges within a slight aura of light. The bible in her hand was also rendered in exquisite detail from cochineal red in Rubens’ unmistakable mastery of his brush, which makes his subjects feel as alive as if they were in front of you.

Alamy

AlamyMoving forward toward modernism – it wasn’t until the middle of the 19th Century that cochineal was replaced by synthetic alternatives as the pre-eminent red dyestuff in the world – impressionist painters continued to make use of the heavenly red hues imported from Mexico. At the Palacio de Bellas Artes, works by Paul Gauguin, Auguste Renoir and Vincent van Gogh have all been analysed and tested positive for cochineal. Like Rubens, Renoir’s subjects seem to be alive on the canvas, but as an impressionist his portraits dissolved into energetic abstractions. Gauguin also used colour, especially red, to create playful accents, but neither compared to the saturation achieved by Van Gogh. His piece, The Bedroom (1888), on loan from the Art Institute of Chicago, puts a full stop on the exhibition with a single burning-hot spot of bright red.

After synthetic pigments became popular, outside of Mexico, the red dye was mass-produced as industrial food colouring – its main use today. Yet while the newly independent Mexico no longer controlled the valuable monopoly on cochineal, it also got something back – the sacred red that had been plundered and proliferated by the Spanish. “In Europe, as has happened in many cases, the history of the original people of Mexico has mattered very little,” Sanchez told the BBC, but in Mexico “the colour continues to be associated with ancestral magic [and] protects those who wear attire dyed with cochineal.”

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.