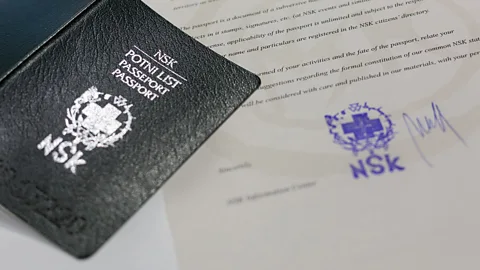

A passport from a country that doesn’t exist

Davide Carpenedo

Davide CarpenedoThe NSK has invented a nation as a work of art – and its pavilion at the Venice Biennale has much to say about statehood and globalisation, writes Benjamin Ramm.

The woman who stamps my passport is called Mercy and she has no fixed abode. Born in Nigeria, she travelled via Libya to Italy, where she lives in the city of Padua in a state of legal limbo. The passport she stamps is issued not by the United Kingdom but by the Neue Slowenische Kunst (NSK), a Slovenian art collective exhibiting at the 2017 Venice Biennale. The purpose of the installation is to explore the meaning of states and statelessness, in part by reversing the experiences of citizen and migrant.

The 57th International Art Exhibition in Venice features 85 national pavilions, from Albania to Zimbabwe, with themes as diverse as the University of Disaster and the Theatre of Glowing Darkness. This year, faced with a rising tide of nationalism, many artists are keen to stress universal identities: there is a Pavilion of Humanity, and a Tunisian installation that issues visitors with a ‘freesa’ (a free visa), endorsing “freedom of movement without the need for arbitrary state-based sanction”.

Davide Carpenedo

Davide CarpenedoThe NSK proclaimed their ‘state’ in 1992, the year after Slovenia declared its independence, as new nations gained sovereignty at the end of the Cold War. “Art is fanaticism that demands diplomacy,” states the inset of my new passport, which declares the owner to be “a participant in the first global state”. NSK regards itself as a “State in Time”, without nation or territory: it “denies the principle of national borders, and it advocates the Transnational Law”.

Davide Carpenedo

Davide CarpenedoOver the last century, passports have come to represent a fundamental aspect of our identity. When IS proclaimed its caliphate, they instructed fighters to tear up their passports, cutting ties with their ‘colonial’ inheritance and committing themselves to a new entity. No less ideological is the utopian World Passport conceived in 1954 by peace activist Garry Davis. Issued by a “world government of world citizens”, it is said to be owned by 10,000 people, but not recognised diplomatically: in 2016, hip-hop artist Mos Def was detained in South Africa for trying to use the document to leave the country.

Authenticity is an essential component of a passport, to the point that it is taken as proof of identity. In 2004, NSK’s headquarters in Ljubljana was inundated by thousands of passport applications from Nigerians based in the southern city of Ibadan. Some correspondents wrote that they had heard NSK was a beautiful country and wished to travel there.

State authority

Visitors to NSK’s pavilion are handed a copy of its newspaper, the front page of which prints an “Apology for Modernity”. “It is cruel to refuse shelter to refugees”, says the editorial. “But it is much more cruel to make people refugees”. NSK regards “the perpetrators of their suffering and misery” to be “the liberal Western world”, the citizens of which “are all complicit in the crimes our elected and unelected leaders have committed. We have become stupid and ugly.”

Alamy

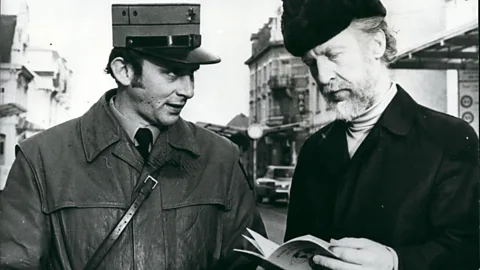

AlamyThis opinion is not rare in the art world (86% of the consulted NSK members endorsed the statement), unlike the group’s dedication to a statist model, which is unfashionable among artists, who tend to be wary of overweening state power. “The state is the basic condition for individuals’ moral and political life, for their freedom”, declares the provocative Apology, which says it is the duty of artists to “reaffirm the majesty of the state both in time and space”.

This stance appeals to NSK’s most famous ambassador, the charismatic and controversial philosopher Slavoj Žižek. Shortly before he delivers a lecture to mark the opening of their pavilion, he tells me that “the uniqueness of NSK is this idea of the ‘stateless state’. It is not, as some leftists think, just a parody. They are not mocking the state, and this assumption reveals a typical liberal fear: what if some people take it seriously and are seduced? But they are to be taken seriously!”

Alamy

AlamyA Leninist by inclination, Žižek has written that the NSK collective should be committed to “a state art in the service of a still non-existent country. It must abandon the celebration of islands of privacy, seemingly insulated from the machinery of authority, and must voluntarily become a small cog in this machinery”. When I suggest that state art is at best banal, at worst coercive, he replies that “NSK are state artists only of their own state!”

It could be said that Žižek underestimates the arbitrary tyranny of bureaucracy – as testified by artists throughout the 20th Century. The curators of NSK’s pavilion argue that its state is “free from the weight of the crimes of older states. It can breathe the air of statehood without choking”. Yet the burden of states lies not only in their collective past, but in their essential bureaucratic structure, which tends to ever greater accumulation of information and influence over citizens.

Davide Carpenedo

Davide CarpenedoWhen I challenge Žižek on this point, he recounts his experience of speaking to refugees travelling through Europe. “Police wanted to register them, and they said ‘No, we are not cattle – we are humans’. But they wanted to go to Norway – the most organised state you can imagine! Because that’s how the welfare state functions”.

Having it both ways?

The refugee experience is not uniform (some flee from tyrannous states, others from lawless statelessness) but Žižek’s statement reveals a tension at the heart of NSK’s work. Their passport claims it is “a document of a subversive nature” but it replicates the same bureaucratic processes it purports to critique. The applicant is charged with listing personal particulars (such as blood type) that are stored in a state register.

I suggest to Žižek that more accountable and direct forms of democracy have been devised using local models – after all, we are speaking in Venice, once an independent republican city state, resistant to the authority of larger political and religious entities. But Žižek argues that city democracy is nearly always run by an urban elite (much like Venice’s Biennale). He points out that many of the problems we face today – from the environment to the migration crisis – require supra-national structures such as the EU.

Žižek’s scepticism about local democracy derives in part from his understanding of the ethnic tensions that exploded in the Balkans in the 1990s. In the NSK newspaper, he writes that “there is nothing liberating about the breaking of state authority... utopian energy is no longer directed towards a stateless community, but towards a state without a nation, a state which would no longer be founded on an ethnic community and its territory”. In this vein, Žižek argues that “it is today’s anti-immigrant populists who are the true threat to the European Enlightenment”. He tells me that our commitment to refugee rights should not be dependent on heart-rending stories of dispossession, but on civic principles: “you shouldn’t like them because they have a nice story to tell – no, you like them irrespective of their story, because human rights are totally abstract rights. We will solve this crisis through geopolitics, not by asking ‘how open will our heart be?’”.

Within an hour of the opening of NSK’s pavilion, there is a lengthy queue to view the main installation. It revolves around a daring and disorientating room slanted at an angle of 45 degrees. The gradation is acute enough to force the visitor to struggle to maintain balance, which is best achieved by adopting the pose of a surfer, or leaning on the display panels. The artist Ahmet Ögüt confirms that the effect is to ensure that visitors are intensely focused – this is not an exhibition for casual perusal. It may not be easy to throw off our inherited identities, but we can at least bring a degree of attention to the issues that confront us, and seek to navigate a solution.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.