The family tragedy that inspired the Brontës' greatest books

BBC

BBCAs a new tale of the famous literary sisters arrives on TV, Hephzibah Anderson takes a look at how their strange and sad history inspired ‘the best writers’ group that ever was’.

Bookworms feel about the Brontës much the way that music buffs feel about The Beatles. You’re either a Charlotte devotee or an Emily enthusiast. Or maybe, just maybe, you’re a fan of Anne. Even so, the idea of these country parson’s daughters leaving behind such indelible novels of gothic passion and wild romanticism is compelling enough that it’s impossible not to think of them as a single unit, like some literary girl band. For all their differences they remain, quite simply, the Brontës.

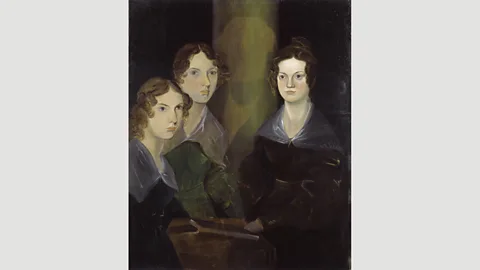

With three larger-than-life sisters (even Anne’s relative obscurity seems writ extra large), it’s little wonder that the fourth Bronte, their brother Branwell, often gets forgotten. This festive season, a one-off drama by multi-BAFTA award winner Sally Wainwright has restored him to the family portrait. And what a portrait it is.

Branwell Brontë/National Portrait Gallery

Branwell Brontë/National Portrait Gallery“We wove a web in childhood, a web of sunny air,” utters the voice of Finn Atkins’ Charlotte at the start of To Walk Invisible. She’s quoting from her character’s 1835 poem about creativity, innocence and mortality, and its incantatory lines are accompanied by mesmerising images: the Brontë brood are still children, clutching toy soldiers and immersed in their make-believe world of Angria and Gondal. Around their heads flicker wreathes of amber flames, signifying the fervour of their imaginations.

From these opening moments on, the film sets out to reclaim the Brontës from the tide of twee that has posthumously engulfed them – think ‘Which Bronte are you?’ quizzes and cosy merchandising (Brontë oven mitts, anyone?). By the time the credits roll, their fierceness and the force of their ambition has been restored to them, along with their individuality and with it, their rivalries.

Branwell is his sisters’ equal to start with, but the film is set primarily during the final three years of his short life, and he cuts a squalid, self-pitying figure for much of it. At the very moment when his sisters’ dreams were acquiring substance (1847 saw the publication of Charlotte’s Jane Eyre, Emily’s Wuthering Heights and Anne’s Agnes Grey), Branwell was sinking into alcoholism and drug addiction. And while they were battling to circumvent the sexism of the age, publishing under male pseudonyms, he pinned his hopes for artistic freedom on marrying into a life of leisure. Inevitably, his relationship with his sisters – and theirs with each other – became increasingly challenging.

Family affairs

Hovering in the film’s background is their clever, unusual father, who propelled himself from hardscrabble Ireland to Cambridge University. He carried a loaded pistol with him at all times and yet instilled a passion for literature in his daughters as well as his son. Patrick Brontë was born in County Down in 1777. He was ordained as an Anglican priest in 1806 and met and married middle class Maria Branwell six years later (“my saucy Pat” she calls him in a surviving love letter). A spirited Cornish native, Maria died less than a decade later, having borne six children, five of them in as many years. By then, the family had moved to Haworth, a village on the edge of the Yorkshire Moors.

Charlotte, the eldest surviving child, was five when she lost her mother, Branwell was four, Emily three, and Anne not yet two. It’s no surprise that, again and again, mothers are lost young in the sisters’ fiction. Two years later, in 1825, their two elder sisters, Maria and Elizabeth, died within six weeks of one another from tuberculosis contracted while away at school.

Options were limited for a modestly salaried man seeking to educate his daughters, and Charlotte and Emily also boarded at the Clergy Daughters’ School at Cowan Bridge, but it was a harsh place, the inspiration for Jane Eyre’s grim Lowood, where a young Jane goes cold and hungry and falls in with a much-abused classmate named Helen Burns, who was based on Charlotte’s lost sister Maria.

The four surviving Brontë children were thrown together back at Haworth, where their widowed father imposed some eccentric rules, like not allowing them to eat meat lest it make them soft. An aunt had come to live with them after their mother’s death, but they were left largely to their own devices, with plenty of time to pursue elaborate role-playing games featuring figures from military history such as the Duke of Wellington and Napoleon.

“The sisters never really seem to have thought about getting married,” notes biographer Claire Harman, whose Charlotte Brontë: A Life was published in 2015. “They all were very interested in battles and statistics and geography – things that girls weren’t traditionally encouraged to think about. They were horribly oppressed by the idea of having to work but at no point did they think ‘I have to be a governess, but hey, I might get married’.”

The boring Brontë?

It was Charlotte’s experience as a governess in Brussels, in a school run by Constantin Heger and his wife, that would sharpen her creative desires. Charlotte developed feelings for Monsieur Heger – feelings that were not reciprocated – and she wanted to be read by him. From Haworth, she wrote him four long letters, which Heger tore up only for his wife to fish out of the bin and piece them back together. These letters were initially hushed up by Charlotte’s friend (the anachronistic term ‘frenemy’ might be more apt) and biographer, Mrs Gaskell. Their steaminess countered the saintly image of Charlotte that she was intent on portraying. For Harman, however, they tell a vivid story of human nature and female experience. As she puts it, they’re “fuelled by hormones, eroticism, youthful anger and all sorts of amazing stuff”.

Scholars have often questioned whether Anne would have been published had it not been for her famous siblings. According to Harman, the same could be asked of Emily. “She clearly is a genius but I think she was very controlling, probably slightly autistic. Wuthering Heights is such a strange book, full of violence and peculiarity. People say it’s their favourite romantic novel but it’s hardly a model for romantic love; there’s a load of anger and energy, and people get thumped across rooms all the time. Whether that book would ever have been published – or finished – is really doubtful if they hadn’t all been together.

Alamy

Alamy“What appeals to me about them as a group is the intensity with which they lived and wrote, and also how it could so very, very easily not have got out into the published world and into posterity’s grasp,” Harman says.

And yet that unity hasn’t always been beneficial. “Lumping them all together irons out their complexities,” says author and playwright Samantha Ellis. It’s particularly hurt Anne, the subject of her new book, Take Courage: Anne Bronte and the Art of Life (its title is taken from Anne’s last words).

Ellis admits that she’d always dismissed Anne as “the boring Brontë”. That changed when she was offered the chance to don latex gloves and examine some relics at the Brontë Parsonage Museum. She was excited to see Charlotte’s minuscule books and Emily’s raging sketches, but Anne’s final letter didn’t much interest her – until she started reading it.

“I’d believed Charlotte when she said Anne was gloomy, less talented than her sisters and spent her whole life preparing for an early death. But in the letter, Anne seemed completely different: clever, bold, and wanting more life. I started to wonder why she’d been neglected, and had a hunch it might be because she was just too radical.

“I certainly don’t think she’s boring or untalented or gloomy any more. I think she was the most radical. I also had to face the fact that one of the main reasons she has been neglected is because her sister Charlotte actively suppressed her best book, The Tenant of Wildfell Hall.”

Alamy

Alamy“They have such varied temperaments,” notes Claire Harman. “It’s a fascinating laboratory experiment – you get this DNA, you stick it in these bizarre conditions, and out come these totally different but clearly very closely related classic novelists.” For Ellis, the resulting friction between them was a source of inspiration and helped them define themselves. “They were [probably] the best writers’ group that ever was.”

Branwell was a key part of that group, and you need only consider the heroes and antiheroes in Charlotte, Emily and Anne’s novels to see how Branwell’s unravelling and their particular responses to it found its way into their work. His self-destructive end provides much of To Walk Invisible’s drama, and yet even here, his sturm und drang is eclipsed by his sisters’ accomplishments. Ultimately, that is just as it should be.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

This story is a part of BBC Britain – a series focused on exploring this extraordinary island, one story at a time. Readers outside of the UK can see every BBC Britain story by heading to the Britain homepage; you also can see our latest stories by following us on Facebook and Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital, Travel and Autos, delivered to your inbox every Friday.