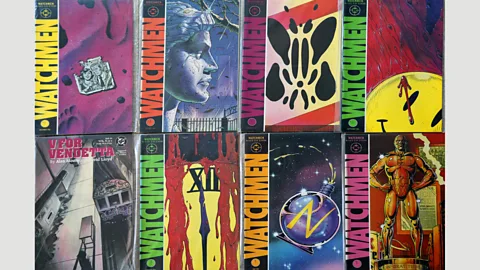

Watchmen: The moment comic books grew up

DC Comics

DC ComicsBefore DC Comics’ Watchmen in 1986, liking comic books was a guilty secret – but Alan Moore’s graphic novel changed all that and paved the way for a current cultural obsession.

It must have been quite something to be a teenage pop fan in the mid-1960s, to hear new singles by The Beatles, The Rolling Stones and Bob Dylan every week, and to realise that your own personal obsession, once dismissed as childish and ephemeral, was now the most revolutionary art form in the world. To those of us who were teenage comics fans in the mid-1980s, something similar happened. Our love of cheaply printed American superhero yarns and their British sci-fi counterparts had previously been a nerdy guilty secret, but now, suddenly, broadsheet newspapers were agreeing that something had changed. Comics couldn’t be ignored. The term ‘graphic novel’ could be used with a straight face.

Mainstream culture’s current fixation on superhero films and TV series can be traced back to this golden age – specifically to the summer of 1986, 30 years ago. The superhero comics of the 1970s and 1980s had already worked hard to convince the public that stories about private detectives wearing capes and masks could be more serious than a portly Adam West dressed up as Batman might have suggested.

Alamy

AlamyThe X-Men scripts written by Chris Claremont emphasised the growing pains of the troubled cast of misfits; John Byrne’s clean, eye-catching artwork brought Hollywood glamour to the pages of The Fantastic Four. But two mini-series published by DC Comics raised the medium to the level of literature, and they both hit newsstands and comic shops within weeks of each other. One was The Dark Knight Returns, a four-issue series, written and drawn by Frank Miller, which reimagined Batman – or rather, “The Batman” – as a middle-aged sadist. The other was Watchmen, a 12-parter from the British writer-artist team of Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons.

Given that they were being written and drawn at the same time, and so they had no chance of influencing one another, it’s remarkable how much the two mini-series have in common. Both of them divide their pages into neat grids of small rectangles, packing in far more information than a typical superhero comic; both of them set their stories in a recognisable, but crumbling US on the verge of nuclear war; both of them ponder what sort of person would put on fancy dress and punch muggers every evening (in short: a crazy person); and both of them ask how such gaudily-garbed do-gooders would be perceived in the media and by the man in the street. Even to the most casual browser, these twin landmarks proved that superhero comics could be as sophisticated as any novel or film, despite all the people in them who strode around wearing underpants over their tights.

Flawed characters

It’s debatable which is the better of the two, but Watchmen is the more ambitious, largely due to its writer, Alan Moore. A long-haired, bushily bearded autodidact from Northampton, Moore was expelled from school for selling LSD, but that didn’t stop him making his mark on two British anthology comics, 2000 AD and Warrior, at the start of the 1980s. Both magazines exploded with wild ideas and unconventional characters, from the blue-skinned, genetically-engineered soldier, Rogue Trooper, to the fascistic future lawman, Judge Dredd. But even among all these eccentric aliens, robots and mutants, the strips written by Moore – The Ballad of Halo Jones, V For Vendetta – stood out: they were funnier, weirder, more erudite, more poetic, and more structurally inventive than anything being done by his peers.

Rex Features

Rex FeaturesMoore was soon invited to revamp Swamp Thing – half-superhero, half-compost heap – for DC Comics, and to write a number of one-off stories about Batman and Superman. Then, when DC bought the rights to some superhero characters from an ailing rival company, Charlton Comics, Moore proposed putting those characters into a grittily believable Cold War setting. He would probe the sexual and emotional hang-ups shared by costumed crime-fighters, and he would explore how international politics might be affected if the US Government had an indestructible, telekinetic genius on the payroll.

Borrowing a phrase from Juvenal, the Roman satirist, he would pose the question, “Who watches the watchmen?” Understandably, DC didn’t want to subject its newly acquired Charlton characters to a grim saga which would leave half of them either disillusioned or dead, but Moore and Gibbons forged ahead with the concept anyway, using their own new characters instead. Each of them would be a dark reflection of a different kind of superhero.

DC Comics

DC ComicsThere was Rorschach, who was a night-stalking vigilante in the Batman tradition, but who was also a foul-smelling Manichean sociopath who intimidated his barfly informants by snapping their fingers. There was Ozymandias, who was a handsome tech boffin, much like Iron Man, but who was also an egomaniac who made a fortune by selling toy figurines of himself. There was the Superman-like Dr Manhattan, a being so powerful that he came to regard the human race as a negligible, inferior species. And there was a crowd of other flawed characters, all of them drawn limpidly by Gibbons with the proportions of actual people rather than musclebound gods.

But it wasn’t just this naturalistic, revisionist angle that was radical; it was the comic’s dazzling narrative complexity. Over the course of its 12 issues, Watchmen grew from being a noirish mystery thriller to an intricate mesh of interlaced stories. It flicked between different points of view, and flitted back and forth through the decades, but a host of recurring symbols and themes tied everything together. It even incorporated a comic-within-a-comic, plus prose sections at the end of each issue. Moore said that he wanted it to be “a superhero Moby Dick; something with that sort of weight, that sort of density” - and he wasn’t far off. The medium had never known anything as richly intricate.

Bad influence?

Watchmen was an immediate commercial and critical hit. In sales terms, it propelled DC Comics ahead of Marvel, its main competitor in the superhero business. And it was adored by reviewers: Time magazine declared it to be one of the 100 greatest novels published since 1923 – the only comic to make it onto the list.

But Moore wasn’t happy about all this success. For one thing, he felt that he had been conned by DC. His deal with the publisher stated that the rights to the characters would revert to him and Gibbons once the series went out of print, but that never happened. As a collected edition, Watchmen has been in print ever since. Moore was also disenchanted by the countless cynical comics about bloodthirsty superheroes which he inspired. “I despaired of the effect that Watchmen had had on the comics industry,” he once told me, “because what I’d hoped that people would take from it was the approach to storytelling, the worldview, the approach to reality as a web of co-incidences and chance remarks. But I think what they took from it was ... Rorschach. What they took from it was, ‘This guy’s really violent, and he’s psychopathic, therefore let’s make all the characters violent psychopaths.’ For a long time, looking at comics was like being in a hall of mirrors in a funfair, where you can only see ugly, distorted reflections of yourself.”

DC

DCCharacteristically, Moore wanted nothing to do with Zack Snyder’s Watchmen film, which was released in 2009. He allowed the film to be made, so that Gibbons could collect a cheque from Hollywood, but he refused to take any money himself, and insisted that his name be taken off the credits. But whether or not Moore likes it, Watchmen and The Dark Knight Returns had a profound impact on popular culture. They set the standard against which every new superhero comic since 1986 has been judged. And, crucially, it wasn’t just comics that were altered, but other media, too. The DNA of these two masterpieces has been passed onto every film and TV series that claims to have a mature take on the superhero genre, from The Incredibles to Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice. Who watches the watchmen? These days, we all do.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital, Travel and Autos, delivered to your inbox every Friday.