What’s so good about Citizen Kane?

Alamy

AlamyIt has topped BBC Culture’s list of the greatest American films – and many other polls before. But what’s so good about Citizen Kane? Nicholas Barber explains.

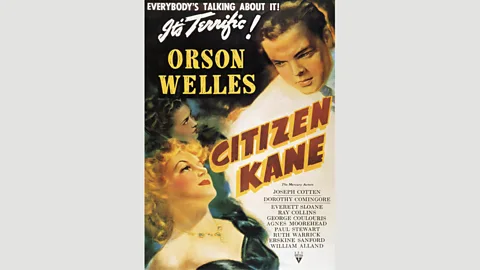

“It’s Terrific!” The slogan on the original Citizen Kane posters may have been on the vague side, but it was certainly accurate. Orson Welles’ debut film received awestruck reviews as soon as it opened in 1941 – Bosley Crowther of the New York Times said it “comes close to being the most sensational film ever made in Hollywood” – and since then it has been picked regularly as the Greatest Film Ever Made. In Sight & Sound magazine’s once-a-decade critics’ and directors’ poll, it held onto the top spot from 1962 to 2002 (only to be dislodged by Hitchcock’s Vertigo in 2012). And now it’s been chosen as the greatest American film ever in BBC Culture’s critics’ poll.

Alamy

AlamyTo be fair, Citizen Kane doesn’t head every greatest films list. Last year, it stalled at number 33 in Empire magazine’s readers’ poll (number one was The Empire Strikes Back). And, at the time of writing, the users of IMDB had put it in 67th place, reserving the winner’s podium for The Shawshank Redemption. There’s nothing shameful about being the 67th finest motion picture in existence, of course, but it’s clear that the average movie fan doesn’t cherish Citizen Kane quite as much as critics, directors and students – that is, people who are obsessed by the nuts and bolts of how films are assembled. It’s a division that makes sense. In 1946, a French cinema historian, Georges Sadoul, dismissed Citizen Kane as “an encyclopedia of old techniques”, and, while he was hoping to dent Welles’ reputation for groundbreaking innovation, he accidentally summed up the film’s geekish appeal. Citizen Kane is an encyclopedia of techniques: a 114-minute film school which provides lesson after lesson in deep focus and rear projection, extreme close-ups and overlapping dialogue. The reason it’s so vibrant is that its own director was learning those lessons too.

Along the way, he was telling the life story of Charles Foster Kane (played by Welles), a press baron who has enormous wealth and influence, but doesn’t attain either the political office or the love he craves. A fictionalised version of William Randolph Hearst, it’s this towering central character that gives the film its air of significance, as well as its continuing air of relevance: the parallels with Citizen Murdoch, Citizen Trump and Citizen Jobs are easy to spot. But rather than playing out like a conventional biopic, Citizen Kane is a jigsaw puzzle that pieces together multiple narrators and multiple perspectives. It spans multiple genres, too. The cover of my Universal Cinema Classics DVD categorises it as a “mystery drama”, but an exhaustive list of its genres would take up the whole box.

Genre bender

The film opens with Bernard Herrmann’s doom-and-gloom chords, and we see the jagged silhouette of a castle on a foggy hilltop. We’re in gothic horror territory; the castle could well be owned by Count Dracula. We then glide into the castle for a weird montage: a snowstorm, a snow globe, Kane’s mouth as he breathes his dying word, “Rosebud.” Two minutes in, and the film isn’t a horror movie anymore, but a surrealist experiment worthy of Dalí and Buñuel.

But not for long. After a few more seconds, Citizen Kane becomes a booming newsreel which romps through Kane’s biography and shows us around Xanadu, his monumental Florida estate (modelled closely on Hearst Castle in San Simeon, California). This estate, we’re told, contains enough antiques to fill “10 museums”, alongside “the largest private zoo since Noah”. But then, just as we’re settling into a hearty faux-documentary, the film changes gear again. There’s a Dickensian flashback to Kane’s rural childhood in 1871. It becomes a wisecracking newsroom comedy when Kane takes control of the New York Inquirer. Later, the film is a political drama, then a backstage farce, then a dark melodrama. And, threading the various genres together, there is a detective yarn about a sleuthing reporter trying to uncover what “Rosebud” might actually mean. No wonder film students love Citizen Kane. Watch it and you’ve ticked off a whole term’s work in a single afternoon.

But don’t mistake it for a dry, academic textbook. Citizen Kane has even more to offer as entertainment than it does as education. Partly, that’s because of the screenplay’s firecracker wit. Co-written by Herman J Mankiewicz, a veteran of dozens of comedies from the 1920s and 1930s, the script bursts with quotable one-liners and exchanges, such as when Kane meets his estranged friend and employee, Jed (Joseph Cotten). “I didn’t know we were speaking,” says Jed. “Sure, we’re speaking, Jedediah,” Kane replies. “You’re fired.”

Alamy

AlamyMore important than the screenplay, though, was Welles’ own vivacity: no other meditation on failure, regret, and the cruelty of time has ever had such youthful exuberance. Astoundingly, Welles was only 25 when Citizen Kane was released. Already a star in the theatre and on the radio, he was lured to Hollywood by RKO Pictures with the promise that he could make any film he wanted, without interference. Previously, he hadn’t been interested in cinema: an assistant named Miriam Geiger had to put together a handbook of the different lenses and shots he might try. But he was soon enthralled by the possibilities that the movies opened up, and he made use of them all in Citizen Kane. A film studio, he quipped, was the “the biggest electric-train set any boy ever had”.

‘Vitality squared’

In Simon Callow’s biography of Welles, he says that the director’s brio gives the film “a freshness and verve which 50 years has done nothing to diminish” (70 years now). In her New Yorker essay on Citizen Kane, Pauline Kael states that its success is “the result of Welles’ discovery of – and delight in – the fun of making movies”. Its true magic, however, is in the way that this delight bounces back and forth between the film-maker and his subject. Much of Citizen Kane concerns a prodigy who is glorying in his power and confidence – and it’s made by a prodigy who is glorying in his power and confidence too. It doesn’t just have vitality, but vitality squared.

Alamy

AlamyInevitably, many subsequent films have some of that same ebullience: Martin Scorsese’s The Wolf of Wall Street recreates the scene in which Kane throws a party for his newspaper staff, and their office is invaded by a marching band and a high-kicking chorus line. But not even Scorsese’s eternally boyish dynamism can match that of Welles when he was making Citizen Kane. No-one’s can. Today, no first-time director in his mid-twenties would be given such complete control of a major project. And no first-time director could possibly come to Hollywood with Welles’ naive ignorance and arrogance about what could be achieved. In 1941, Welles was both beginner and expert, undergraduate and professor, young Charlie and old Charles Foster. And if he never had the boundless freedom and energy to make another film like Citizen Kane, neither did anyone else. It’s terrific.