Why transgender people are ignored by modern medicine

Getty Images

Getty ImagesGender is fundamental to many decisions in health care systems around the world – and this puts transgender people in a vulnerable position.

It was 2016 and Cameron Whitley was gravely ill. He was urgently in need of a kidney transplant, which should have been no problem. He was young and otherwise healthy. He had medical insurance. He even had several gallant friends willing to undergo major surgery for him.

There was a catch, however. His doctors were missing a crucial piece of information – one which, until then, no one had thought to look into. Without it, they weren’t able to put him on the list.

And so, more than a year after he first turned up at a hospital in the US Midwest with mysterious ear pain – eventually leading to a diagnosis of chronic kidney disease – he was forced to go on dialysis. By this point, his organs were functioning at less than 8% of their normal capacity.

But here again, Whitley hit a snag: his doctors were in need of another vital piece of information – and without it, they couldn’t work out how often he would need this treatment. They had to guess; they got it wrong; he became yet more unwell. All this time, his friends were practically throwing their kidneys at him.

Finally, just as Whitley, who is an assistant professor of sociology at Western Washington University, was approved for a transplant, his dialysis treatment led to massive blood loss and the operation had to be delayed. “It was really hard. I was horribly sick,” he says.

What was going on?

Whitley is a transgender man – he identifies as male but his biological sex is female. He has been living as a man for around 20 years. In his words, he fully “passes” as one, for want of a better term – and he is registered as a man on all his legal documents, from his passport to his medical records.

But most healthcare has evolved with a straightforward dichotomy of gender in mind. Though there are thought to be nearly a million transgender people living in the US (this is a rough estimate as this data isn’t collected) there’s concern that this group is being largely ignored by health services and the medical industry.

Rather than devising new ways to cope with changing social norms, transgender people are often shoehorned into inappropriate boxes instead.

Cameron Whitley

Cameron WhitleyIn Whitley’s case, the problem was how the severity of kidney disease is assessed. The usual protocol is to calculate a patient’s “estimated glomerular filtration rate” (eGFR), which measures the amount of a certain waste product in their blood and therefore shows how efficient their kidneys are at filtering it out. If the eGFR is below a certain level, it’s an indication that their kidneys are failing and they are eligible for a transplant.

There are several different lower limits for an eGFR, depending on things like a person’s weight, age, gender and race, which are intended to reflect the natural variation in the human body. Based on the female cut-off, he would have been allowed a transplant immediately. But he’s registered as a man on his medical records, and this meant his doctors used the male eGFR level. He wasn’t put on the list until he reached it – a decision that ultimately delayed the surgery by over a year, and very nearly cost him his life.

“It was really cute and awesome that I was treated as male, but in being this way, they didn’t necessarily take into account the body,” says Whitley, who points out that, though he has been taking testosterone for around 15 years, it’s a relatively small dose. “I was born female and I identify as male – they should have probably have set my limit as somewhere in the middle.”

You might also like:

Even Whitley’s dialysis was complicated by the current lack of knowledge about transgender medicine – the calculation that’s used to work out how regularly it needs to be done is based on another sex-specific assumption.

Whitley’s experiences are just the tip of the iceberg.

When you factor in the large data gaps in everything from the average life expectancy of transgender people to the right dosages of medications for their bodies, along with the widespread lack of knowledge among doctors about how to address them – let alone treat them – and the high chance of them being refused treatment outright, it soon becomes clear that transgender medicine is in crisis. Few groups experience such significant barriers to healthcare, and yet their struggles are going largely unnoticed.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn some cases, the issues are baked right into the heart of our medical systems.

Consider this: if you were to look through every single medical record in the UK – all 55 million – you won’t find a single record labelled as belonging to a transgender person. This is also true for those assembled by many providers in the US.

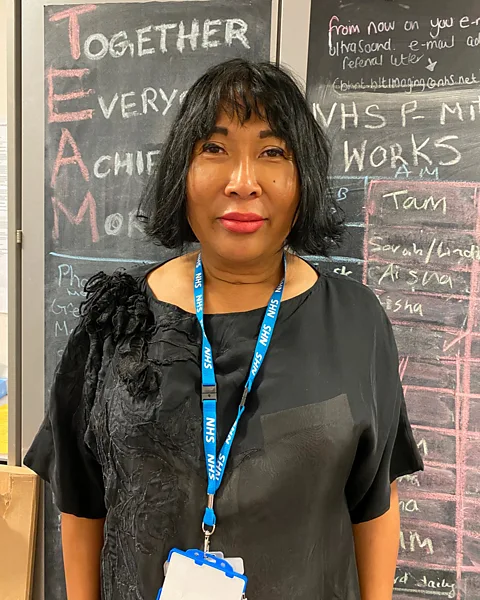

“You can register as male or female, but you can still only choose between these two options – you can’t say if you are transgender or non-binary,” explains Kamilla Kamaruddin, a doctor who works for the National Health Service (NHS) and transgender woman. “So that’s quite difficult.”

Instead doctors must rely on their patient to tell them.

“Sometimes this can be okay,” says Dina Greene, a clinical chemist and expert in transgender health at the University of Washington, Seattle. In many cases, if someone is going to see a medical expert where gender seems irrelevant, patients might not want their doctor to know they are transgender, she says. "It’s stigmatised.”

But this rigid male-female dichotomy also has some bizarre, and much less desirable, implications. “There are lots of simple things, like our medical record systems often cancel pregnancy tests if they're ordered on men,” says Greene. (Some transgender men can get pregnant, depending on the treatment they have had. And though very few countries track this aspect of their health, 250 gave birth in Australia in the decade leading up to 2019).

The gender you’re registered as also dictates which screening tests you are invited to, meaning that thousands of transgender men could be missing out on potentially life-saving cervical (Pap) smears and breast exams, while transgender women could be missing out on abdominal aortic aneurism check-ups (or prostate cancer screenings, if they live in the US).

When Charlie Manzano, a transgender man from Martinez, California, informed his healthcare provider that he would like to register as male, he was told that he would lose his gynaecologist – though he still retained his female reproductive organs. “Most of my doctors have no idea about trans patients,” he says.

Similarly, your gender shapes a number of other medical decisions, such as the dose of drugs you’re prescribed. For those whose gender and sex are the same, this makes sense, because male and female biology is fundamentally different – the former have more water in the body, a higher surface area, and a higher body mass. All of these factors can influence the way pharmaceuticals behave. Females also have more sites for certain drugs to bind to, and are therefore more sensitive to them. They tend to clear them more slowly, so they are more susceptible to overdoses.

Kamilla Kamaruddin

Kamilla KamaruddinDoctors already factor in the importance of tweaking the standard female dosages for pregnant women, who have a higher body weight and are simmering in a cocktail of hormones that change certain aspects of their biology. However, no such considerations are routinely made for transgender people, who, as a result of surgery or hormonal therapies, are known not to respond to certain drugs in the same way.

This is all layered on top of some alarming statistics about transgender health. The group has higher rates of heart disease, certain cancers, mental health problems, suicide, smoking, and substance abuse than the general population – as well as an HIV prevalence which is up to 42 times the national average. Transgender people are not only more likely to get sick, but less likely to seek treatment when they do.

How has this happened – and what can be done to fix it?

Ancient roots

Gender dysphoria is a feeling of unease which occurs when there’s a mismatch between a person’s biological sex – determined by the chromosomes they inherited, which are XX (female) or XY (male) in the vast majority of people – and their gender identity. It’s an ancient phenomenon which dates back at least several thousand years, while gender fluidity might be even older.

Transgender medicine arguably began with the Roman emperor Elagabalus, who reigned from 218 to 222 AD and is considered by some to be the first person to seek sex reassignment surgery. He reportedly asked his doctors to construct a vagina inside his body.

Over the following two millennia, the discipline remained mostly primitive and conceptual, until the doctor Magnus Hirschfeld pioneered treatment for what he called “sexual intermediaries” in the early 20th Century. He founded the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft in Germany, where surgical and hormone therapy was available for patients, who included the Danish painter Lili Elbe. (The institute was later burned down by the Nazis).

From the 1960s, hormone therapy became more accessible. Today, transgender men often take testosterone, which can help them to develop larger muscles, beards and body hair, as well as deep voices – and even sometimes male-pattern baldness – while transgender women often take oestrogen and a drug that blocks the action of their natural testosterone, if they are still producing it. “Puberty blockers” are also sometimes prescribed to children to halt the progress of unwanted traits.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesUntil recently, transgender medicine has generally focused on the process of “transitioning” – changing a person’s physical characteristics so that they align with their gender identity – and not what happens afterwards. But this is changing, and it’s a matter of some urgency.

Ignorance

In 2015, a survey conducted by the Center for American Progress (CAP) found that 29% of the transgender respondents in the sample had been refused healthcare by a doctor because of their gender identity, just in the preceding year alone. For years, it was illegal for doctors to refuse care following protections introduced by the Obama administration. But US President Donald Trump recently reversed them, leading to growing concern about how this might affect transgender people.

“I think this is the biggest problem in transgender health – that people are denied basic care,” says Greene, adding that they often avoid medical institutions at all costs, for fear of this discrimination. Many also find it difficult to get health insurance.

Another big challenge is the widespread lack of knowledge about transgender anatomy, along with ususual levels of curiosity about it. Whitley has first-hand experience of just how common this is.

The first incident occurred when Whitley went for an ultrasound scan to investigate his kidney failure, and the technicians who were assessing him abruptly walked out. “All of a sudden, everyone in the room set their stuff down and just left,” he says. “I was like, ‘what's happening?’ No one said anything.” He was left alone for 20 minutes – and then told that he could go, and that they would call him.

Later, he listened in amazement as a doctor gravely informed him that he had a uterus – a fact that Whitley was, naturally, already aware of. “They said, ‘I think we understand the problem – you have a uterus and so that may be contributing to your kidney failure.’ I was like, ‘what are you talking about?’”

Eventually Whitley’s doctor convinced him to stop his testosterone therapy, though Whitley feels there was no valid medical justification for this and describes it as a distressing and unnecessary step, which may have exacerbated his condition and delayed his eligibility for a transplant. “They were doing my calculations based on me being male, but at the same time they lowered my muscle mass [making this less logical],” he says. “This seems to be a thing that doctors do again and again, like, ‘let me focus on your trans identity and not on your kidney disease’.”

Press Association

Press AssociationIn the end, Whitley, who is now an assistant professor of sociology at Washington University, didn’t receive satisfactory treatment until he moved across the country to the East Coast, where he found a hospital with a more progressive outlook.

Cancer screenings

Even when doctors are well-informed, it can still be difficult for transgender people to access certain potentially life-saving interventions because of the systems that are in place.

“In the UK, people are invited for cancer screenings based on whatever gender they're registered as in their medical records,” says Alison Berner, an oncologist and part-time gender identity specialist.

This means that transgender men won’t be asked to attend screenings for breast and cervical cancer, but they will be invited to have the least useful check-up, the one for abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA). In the UK, patients registered as male are currently invited for these, which involve checking for a bulge in the major artery that runs from a person’s chest to their abdomen; if it’s swollen, it might eventually burst and lead to a medical emergency. It’s extremely rare unless your biological sex is male.

Equally, transgender women who register as female will be summoned for breast and cervical screenings, but they won’t be asked to attend AAA exams. The former is often appropriate, because if they are taking female hormones they will be at a slightly higher risk of breast cancer – but of course this group do not have cervixes, and they could be missing out on important pre-emptive treatments if their AAAs go unnoticed.

If transgender patients don’t attend these inappropriate appointments, the reminders will just keep coming – often becoming increasingly urgent. Kamaruddin recalls an incident which some people might have found upsetting. “I kept receiving letters, so eventually I had to call up and tell them look, I don’t need this. It was the only way to do it,” she says.

The official guidance is that a person’s doctor should make sure that their record “facilitates screening for physiologically appropriate risks”, but there is no easy way to do so, other than adding a comment in their medical notes, which could be easily missed.

Kamaruddin says she keeps a list of her own transgender patients and trains her nurses about the cancer and sexual health screenings they need. They have to contact the relevant hospitals and get them appointments manually. But not only is this inefficient – it’s also unreliable. Only some medical practices keep such lists, and when they do, they depend on patients disclosing their status to their doctor voluntarily – otherwise there is no way of knowing.

Naturally, some patients choose to keep information about their biological sex to themselves. They don’t always realise it’s still relevant after their gender transition. “A lot of transgender men don’t know they need to have cervical screenings,” says Kamaruddin.

For those who identify as non-binary, the situation is even murkier. Roman Ruddick, from California, says the system has no idea what to do with them. “One month they were like, ‘just so you know, you should get your prostate checked’ and I was really thrown off and then the next month I got, ‘you should go get a pap smear’ and I found out that they were just sending me everything.”

Jo Holland/BBC

Jo Holland/BBCOne solution to these issues is to introduce an option to register as transgender or non-binary, rather than simply male or female. But others have floated the idea of a “body organ checklist” – the idea being that you are invited for screenings based on which organs you have, rather than your gender.

“I think that would be an incredibly intelligent way to invite people for these services,” says Berner, who explains that this could also be helpful for other reasons. “For a cisgender woman [one whose gender identity matches their sex] who has, for example, had a traumatic time with cysts, and perhaps lost a pregnancy as a result and had a hysterectomy – for them to get a cervical screening letter through would be particularly distressing as well.”

Ruddick, who was diagnosed with ovarian cancer in high school, and Manzano, who was diagnosed with melanoma, would also like to see health services become less gendered in general. “I don't think that I should have to go to the women's health clinic to go to the gynaecologist,” says Ruddick.

They co-founded the Transgender Cancer Patient Project together in 2018, after realising that there were few support groups available for transgender cancer patients, and a lack of clear, factual information about cancer in this community. “So often articles are just clickbait you know, like with the headline ‘Do trans hormones cause cancer?’,” says Manzano.

Data gaps

Transgender health is also threatened by some sizeable data gaps.

It’s widely and erroneously reported that black transgender people have a life expectancy of just 35. But in reality, scientists have no idea what it is – because no one has ever checked. For important laboratory tests, such as the eGFR and the complete blood count (CBC) – which is routinely used to evaluate the overall health of patients and detect disorders such as anaemia – doctors have, until recently, been forced to guess which limits they should use.

In fact, there’s mounting evidence that – as with many other traits, such as race – gender often defies the binary categories and clear thresholds that much of modern medicine has been built on. Transgender people often have distinctive anatomy and physiology, not just compared to the wider population, but to each other – depending on what kind of treatment they have had.

Science Photo Library

Science Photo LibraryBut while there is a clear need for more tailored medicine, Berner is concerned that the data required to develop it just isn’t being collected. For example, there might be hundreds of transgender women being treated for prostate cancer in the UK, but each oncologist will probably only see one or two cases themselves – and you can’t learn much about what works and what doesn’t, unless you view their data as a group. “We need to work together,” she says.

In the field of anaesthesia, where the ability to dose a patient accurately can mean the difference between life and death, it can be tricky to get this right for transgender people. There has been very little research into how their bodies process drugs, especially after hormone therapy.

Meanwhile Greene has found that when it comes to blood tests, the male version of the calculations should be used for most transgender men and the female version should be used for most transgender women – the process of being treated with hormones actually changes the person’s biology so that it more closely matches their gender identity. “But it depends on the test that’s being evaluated,” she says.

Addressing this missing data isn’t just critical for improving the treatment of transgender people – it could also help to readdress attitudes in the long-run.

“It's basically like a form of erasure, like we have no way to count it, so it must not exist and it must be a very rare thing and not really mean anything,” says Greene. The lack of data is a vicious cycle – because no one knows how many transgender people there are, it’s hard for researchers to justify studying them.

“It’s important to show that this is normal – these people are here,” says Greene. “They exist. They are everywhere.”

So what happened to Whitley? In the end, he got his kidney. It was donated by a close friend who is, incidentally, also transgender. Together with Greene, he wrote a scientific paper about his experiences, which he hopes will help others who are going through the same thing. “I've had messages from a lot of people about it already,” he says. “I’ve even spoken to the parents of transgender kids who are in need of a transplant.”

--

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “The Essential List”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife, and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.