The global challenge of iron deficiency – and why scientists can't agree if supplements are the answer

Getty Images

Getty ImagesA lack of this vital nutrient is one of the world's leading causes of disability – but exactly when it becomes a problem, and the best way to treat it, remains unclear.

When Megan Ryan first noticed her fatigue, she assumed it was normal. After all, she was a single parent to a three-year-old. She also worked full-time. Almost every day, when she picked her son up from daycare, she'd fall asleep with him during his afternoon nap. She didn't think much about it. "I just thought, 'Oh, this is motherhood'," says Ryan, who lives in upstate New York, US. At a routine medical check-up in June 2023, her doctor asked if she felt exhausted. Blood test results showed that Ryan had iron deficiency anaemia.

Looking back, there had been other signs. Despite regularly working out, Ryan had suddenly started to feel winded on routine hikes. She had also had iron deficiency before, during pregnancy. That time, her midwife suspected it after Ryan mentioned that her only pregnancy craving was ice – a classic sign of pica, which is, in turn, a symptom of iron deficiency.

Iron deficiency is the most common micronutrient deficiency in the world today, affecting roughly one in three people. It is especially prevalent among children as well as women of reproductive age, including pregnant women.

The condition can cause a wide range of consequences. When a pregnant woman doesn't have adequate iron stores, for example, it can affect the foetus' brain development and there is also a higher risk of low birth weight, preterm birth, dying during pregnancy and stillbirth. For babies and toddlers, not having enough iron can affect long-term development, with studies finding that children are at risk of exhibiting behavioural issues – they are less happy and contented, and tend to be more socially inhibited. It can also influence children's motor skills, and cognitive ability even years after a deficiency has been corrected. In adults, iron deficiency is one of the world's leading causes of disability. In rare cases, it can be life-threatening.

A widespread issue

"It's a major global problem," says Michael Zimmermann, professor of human nutrition at the University of Oxford in the UK and a long-time researcher of micronutrient deficiencies. "It's very common. It's not going away very fast. And it is associated with a lot of disability."

Most scientists agree that iron deficiency is a common condition. But other questions persist, such as how exactly to define iron deficiency, or how likely it is, in the absence of other symptoms, to raise the risk of poor health outcomes. So, when should, and shouldn't, someone supplement their iron?

What isn't disputed is that some groups are more susceptible to iron deficiency than others.

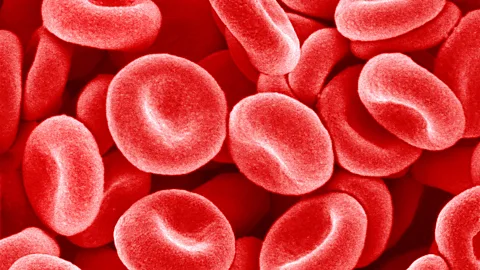

In women, for example, iron-deficiency anaemia – where the body does not have enough iron to make sufficient red blood cells – is a leading cause of disability worldwide. One study of first-time US blood donors found that iron levels were low in 12% of women, but in less than 3% of men, reflecting the impact made by regular blood loss through menstruation. Then there's the impact of pregnancy, which diverts nutrition to the foetus, meaning that women in this group are particularly at risk. One study found that 46% of UK women had anaemia at some point during pregnancy – though not all cases stemmed from iron deficiency.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesEndurance athletics, vegetarianism or veganism and frequent blood donation can all put both men and women at increased risk. People with certain health conditions might also be prone to lower iron levels. Kidney disease and coeliac disease can decrease iron absorption, for example.

A critical time

But children are among the most vulnerable group to iron deficiency because the mineral is so important for their development.

"What's the most rapid period of growth in our entire lifespan? Infancy," says Mark Corkins, chair of the Committee on Nutrition at the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). "You triple your birth weight by a year of age. You double your length." As our bodies grow, they need more blood. And red blood cells are built – in part – on iron. Without that necessary iron, says Corkins, you risk not able to produce enough red blood cells to deliver oxygen to your growing tissues, including the brain.

Iron deficiency is especially common in children from lower income countries. "In studies I've done in Africa, 70% of babies between six and 12 months of age have clear iron-deficiency anaemia," says Zimmermann.

Even in wealthier countries, which have better overall nutrition and which are more likely to fortify certain food products with iron, this deficiency persists. Up to 4% of toddlers in the US, for example, have iron-deficiency anaemia, while some 15% have iron deficiency.

Iron deficiency, iron-deficiency anaemia, and anaemia

Anaemia occurs when someone is not producing enough normal red blood cells or haemoglobin, the substance that carries oxygen around in your blood. While this can be due to various factors, around half of all anaemia cases are caused by iron deficiency. Adults with this condition, iron-deficiency anaemia, might experience weakness, extreme fatigue, or shortness of breath, among other symptoms. Symptoms in babies and small children are similar, though they might also have sleep issues – particularly frequent night wakes, restlessness during sleep, and difficulty falling asleep.

Just because someone is iron deficient does not necessarily mean they will have anaemia. "Iron deficiency can be considered a stage prior to anaemia," says clinical haemotologist Sant-Rayn Pasricha, the head of the Melbourne School of Population and Global Health who specialises in iron deficiency and related conditions.

The severity of the deficiency plays a key role, Pasricha explains. When someone gets low on iron, their body begins to form red blood cells differently, he says. They get smaller and, eventually, the amount of oxygen-carrying haemoglobin in that person's blood drops below a healthy level. "That's when we reach iron deficiency anaemia," Pasricha says.

Iron deficiency and anaemia are generally diagnosed with a blood test – usually one that examines levels of ferritin, a protein that helps store iron, or haemoglobin.

A matter of debate

Some specialists question whether iron deficiency is always a cause for concern – especially if it arises in the absence of any physical symptoms and if the patient does not have anaemia.

Pasricha co-authored a review to help inform the World Health Organization's guidelines on iron supplementation in women. In that research, he found something interesting.

While those women in clinical trials who were iron deficient and reported feeling fatigued found that their fatigue improved upon taking iron supplements, the intervention didn't change the energy levels of women who were also iron deficient, but who had not reported fatigue.

"This hints to us that, at least in adults, if you're clinically unwell with an iron deficiency, then of course you should be treated and that will improve how you feel," Pasricha says. "But it also suggests that, if you're feeling perfectly fine, and someone just finds that you have a low iron level – then it's hard to be sure that that treating you then would boost you to feel any different."

Overall, iron deficiency in the absence of anaemia has been studied less than iron-deficiency anaemia. But there are some broad conclusions we can make, researchers say.

"The consensus is that iron-deficiency anaemia is certainly worse," says Zimmermann. "But iron deficiency is also associated with impairment."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAccording to some studies, the effects of iron-deficiency anaemia – particularly in children – can be long-lasting. "It's not just about [poor health outcomes] – it is that you didn't maximise your development," Corkins says.

One review, for example, found a "consistent association" between children with iron-deficiency anaemia having poorer cognitive performance compared to controls. However, the researchers note, perhaps it's not iron-deficiency anaemia that's the problem. It could be the effect of anaemia in general, which depresses energy levels. The researchers also say in their review that it is hard to rule out the influence of socioeconomic factors on children’s behaviour and cognition.

This complexity lies at the heart of all nutrition research: is it the absence of a nutrient itself that's the problem, or is that deficiency a sign of something else going on?

To complicate matters further, the criteria for defining iron deficiency in children is still up for debate, says Zimmermann. Because children are growing so fast, he adds, iron deficiency normally quickly leads to anaemia – which means it's not easy to find, and study, iron-deficient children who are not anaemic.

To supplement or not to supplement

Given that, and the potential consequences for their development, guidelines often advise supplementing children with iron at any sign of deficiency – or even to supplement as a prevention measure.

In the US, for example, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that babies who are exclusively breastfed receive iron drops from four months old, for example. This is because breastmilk has low levels of iron, while formula milk is usually fortified.

But some researchers question this approach.

Pasricha was involved in the largest trial to date that has examined the effect of supplementation on child development, he says. The study, of 3,300 eight-month-old babies in Bangladesh, randomised children into groups that received either daily iron supplementation for three months, or a placebo. He and colleagues measured the children's neurodevelopment before and after the supplementation. "We did not see any evidence of a functional benefit," he says, although they also saw no harm either way.

"We did see that haemoglobin and iron status did improve in the children that received iron – but we didn't see that affect child development," says Pasricha. The "why", he says, "is something that the team is really grappling with".

Other research has yielded similar findings. For example, in one study, even after infants with iron-deficiency anaemia received supplementation that corrected their anaemia, they continued to show more restless sleep patterns than their cohorts – sometimes even years later.

One possible reason might be that even a brief period of deficiency can lead to long-lasting harm. One study, for example, found that when children had had iron deficiency at birth, they had less activation in the regions of their brain related to cognitive control at eight to 11 years old – even if their iron levels had been corrected.

But another possibility, Pasricha says, is that it isn't the low iron itself that causes poorer development, but that low iron is an indicator of something else – such as other nutrients in a person's diet that are missing.

Meanwhile, there could also be downsides to supplementing children who don't actually have a deficiency. Some studies have found that babies and toddlers who had adequate iron levels, but received supplementation, had poorer weight gain and less growth compared to controls. Randomised controlled trials have found that babies randomly assigned to high-iron formula milk scored more poorly on cognitive tests of abilities like visual memory, reading comprehension and mathematics at both 10 years old and 16 years old, compared to those on a low-iron formulation. However, exactly how much iron supplementation would avoid these effects remains unclear, the researchers say as other factors could also be involved.

Given results like this, however, some experts have criticised US guidelines to supplement all breastfed infants.

Supplements can also have other side effects. Zimmermann, for example, has studied how supplementation can affect people's microbiome. Bacteria thrive on iron, he says. The very small amount of iron that breastmilk has is bound to protective substances like lactoferrin, which helps to keep iron away from potential pathogens in the gut – especially protective for babies, who have immature immune systems. Giving a baby aged six months old micronutrient powders containing iron, which is what many experts recommend, could result in a negative outcome, says Zimmermann.

"These powders have very high amounts of iron in them… which can cause a very rapid shift in the microbiome," says Zimmermann. The babies can't absorb all that iron, which ends up impacting their gut microbiome – potentially towards a balance favouring "the pathogens we worry most about in babies", he says. This includes E. coli, which grows prolifically in the presence of iron.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMany clinicians and researchers agree, however, that when someone has iron deficiency or iron-deficiency anaemia along with symptoms, supplementing can be one of the fastest ways to help them improve. One review of iron deficiency in endurance athletes, for example, found that supplementation not only improved ferritin and haemoglobin, but athletes' aerobic capacity, too.

Whether to take supplements – or give them to a child – is something that people should decide with the help of a doctor, experts say.

A balanced diet

But in an ideal world, people would get sufficient iron by eating a balanced diet that includes iron-rich foods, and avoid developing a deficiency in the first place – though this is not always possible. Ingredients such as liver or red meat, pulses, including kidney and edamame beans and chickpeas, as well as nuts and dried fruits are all considered good sources of iron.

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that infants aged six to 12 months need 11 mg of iron per day. For toddlers, they recommend 7 mg, and for four- to eight-year-olds, 10 mg.

Part of the higher recommendation for younger babies is because of their rapid development, experts say. But it's also because there is an assumption being made that most infants' first solids will be foods like iron-fortified cereals, as well as fruits and vegetables – non-heme sources of iron, which the body absorbs less readily than heme sources, which are animal-derived, like meat, fish and eggs.

"Diet is the best approach. Your body tends to take it up better. Your body tends to use it better," Corkins says. "Now, if someone is profoundly anaemic, and you're trying to get them fixed faster – then you do supplementation."

As for Ryan, she was able to correct her iron deficiency both times it happened: in pregnancy, with a supplement, and in 2023, with iron infusions, administered at her hospital, every two weeks for five months. "It wasn't a quick fix," she says. With time, however, she noticed her fatigue fade.

Disclaimer

All content within this column is provided for general information only, and should not be treated as a substitute for the medical advice of a doctor or any other health care professional. The BBC is not responsible or liable for any diagnosis made by a user based on the content of this site. The BBC is not liable for the contents of any external internet sites listed, nor does it endorse any commercial product or service mentioned or advised on any of the sites. Always consult your own GP if you're in any way concerned about your health.

--

For trusted insights into better health and wellbeing rooted in science, sign up to the Health Fix newsletter, while The Essential List delivers a handpicked selection of features and insights.